This article originally appeared in the February 2024 issue of CONNECT.

Misha Husic (Hyogo Prefecture)

What was once a gateway for Japanese people to experience Western life has, over time, evolved into a way for Westerners to experience a part of Japanese life.

Food and drink are often the first things that come to mind when we think about other cultures. Restaurants, cafes and similar establishments are one of the easiest and most common ways to experience and directly engage with countless cultures different from your own, whether you’re travelling abroad or just exploring new places in your hometown. And of course, this is true for Japan as well. While we may immediately think of sushi restaurants, ramen shops and tea houses as representative of Japanese culture, within Japan itself, coffee shops have served an important role as cultural conduits over the past century or so.

From their inception, Japanese coffee shops were rooted in cultural exchange. The very first Japanese coffee shop opened in 1888—right in the middle of the Meiji era, a time of rapid Westernization in Japan (1). The owner of this shop, Tei Ei-Kei, was born in Nagasaki in 1859 and raised by Tei Ei-Nei, the Taiwanese Secretary of Japan’s Foreign Ministry at the time. Tei Ei-Kei’s upbringing was incredibly multicultural, and he learned to speak four languages in his youth: Japanese, Chinese, French and English. In 1877, at the age of 16, he travelled to the United States to study at Yale. During his two-year stay abroad Tei Ei-Kei developed a liking for coffee, and on his way back to Japan through Europe, he visited many well-known coffee shops in the United Kingdom (1) (2). He was particularly drawn to London’s “penny universities,” a name that British coffee houses earned by dint of their reputation as places for disseminating news, discussing politics, and holding informal lessons on various topics. Guests could partake in these activities for the price of a coffee: a single penny (3).

Tei Ei-Kei eventually opened his own coffee shop in Tokyo, called Kahiichakan (可否茶館) (1) (2). His time abroad meant that Kahiichakan was closer to the British coffee houses and gentlemen’s clubs that he had experienced than to any standard Japanese food establishment. Its decor and amenities included leather furniture, billiard tables, various smoking paraphernalia and more, and its clients were entirely men. Tei Ei-Kei described Kahiichakan as “a space to share knowledge, a social salon where ordinary people, students and youths could gather” (1), undoubtedly evoking the imagery of the penny universities he visited in Europe. His shop closed after only five years of business, but during its run it certainly offered patrons a taste of life overseas. And much like their British counterparts, Kahiichakan and other early Japanese coffee shops quickly developed into local centres of information and cultural exchange.

As hubs of knowledge, these coffee shops, called kissaten (喫茶店), were essential resources for city life in the mid-to-late Meiji era (4). During this time, along with rapid modernization Japan saw a large influx of people moving from rural to urban areas, and kissaten became common meeting grounds for these newly-arrived residents. Aside from their Western-inspired aesthetics and menus, they served as spaces where new folks could gather to learn about the ways of city life from locals, forge new connections and settle into their new communities. They were also spaces for people to meet with others from their home regions, speak their hometown dialects again and share aspects of life from these areas with others. As people continued moving into cities from elsewhere, coffee shops gradually developed into trendy spots where patrons from all walks of life could be found.

By the end of the Meiji era, the Japanese image of a coffee shop was firmly that of a modern place, at a time when “modern” was still largely equated with “Western” (1) (2). Coffee shops still leaned heavily into Western influence for everything from their design and atmosphere, food, tableware and cutlery, even to the employee uniforms and customer-employee interactions (5). Instead of going to a counter to order or using ticketing systems common at the time, customers were typically seated first and their orders were taken by the staff directly at their seat (6). Western dishes and drinks were brought by waitresses to patrons in wood chairs and tables covered in crisp, white tablecloths, a sharp contrast to the traditional Japanese tea shop’s tatami floors, minimal furniture and tea ceremony customs. Throughout this period, the clientele also shifted from predominantly male to all genders. Particularly common were the moga (modern girls; モダンガール) and mobo (modern boys; モダンボーイ), fashionable young people of the day known for their Westernised style and conduct (2). Many of the coffee shops they frequented were located in Ginza, an area of Tokyo that to this day is associated with the Western upper class (5).

While the coffee shops of the late 1800s and early 1900s took much of their Western influence from Europe, by the mid-1920s public taste had shifted more towards an American edge, bringing with it the sounds of jazz to Japanese cafés (6). As intercontinental travel became more accessible, Japanese people who had been to the United States brought jazz records back with them to Japan. These records were often then played in cafés for other customers to enjoy. As the connection between coffee shops and jazz music grew, the jazz kissa (ジャズ喫茶) developed as a door to Western jazz and music culture. Musicians and music-lovers came to these shops to discover new American jazz artists, listen to their favourite records, or simply enjoy the music because they couldn’t afford to have a personal record collection (7). By the 1950s, jazz kissa were one of the most popular ways for Japanese people to listen to jazz. Today, Japan has one of the largest jazz communities in the world, undoubtedly due in part to these opportunities that jazz kissa provided for the Japanese public to connect with jazz and other music from different cultures.

Much like jazz, which started as a Western import and eventually developed a unique Japanese variant, the quintessential Japanese kissaten would likewise develop over time. The kissaten of the late 20th century became a place for the everyday person to visit, either by themselves or in a small group of friends. The atmosphere was determined by the owner’s personality, and the relationship between the owner and the guests became an important part of the shop’s character (2). While a Western influence can still be felt in Japan’s coffee scene—especially considering the popularity and number of Western coffee chains including Starbucks, Seattle’s Best, Tully’s and others—many traditional coffee shops are still operating today, much in the same way as they were decades ago. The retro feel and long history of these classic shops has made them somewhat like a time capsule, preserving the Japanese coffee culture of days long gone. Since the 1980s, such shops have waned in popularity as modern chains and independent cafes have gained traction; however, the pendulum might be swinging back in their favour (8) (9).

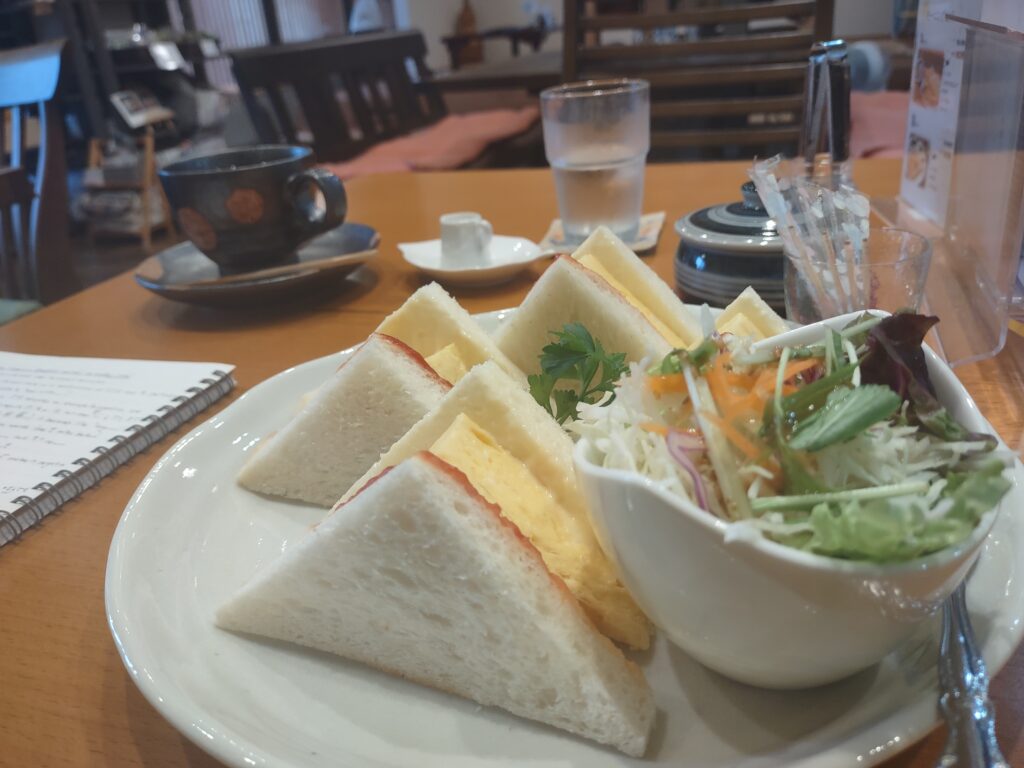

There has been an interesting phenomenon noted recently of the traditional kissaten seeing somewhat of a resurgence in Japan (8). Young people especially have been going to these coffee houses for the unique, almost sentimental atmosphere that they have. Inside dark spaces with rich mahogany furniture and air often heavy with cigarette smoke, a small team of staff in black and white uniforms work behind long bar-like counters. They often brew darker roasts of coffee, as either a pour-over or using the rather beautiful and sometimes even mediaeval-looking syphon method. Their drinks are served in glasses or colourful china with floral patterns, and light meals such as toast or cakes are often available. All of these elements evoke the feeling of a time gone by, and what may have felt dated 20 or 30 years ago now holds a certain allure precisely because of the nostalgia that it carries. The recent spike in the popularity of such coffee shops speaks to a curiosity about the history and even the tradition of Japanese coffee houses from both locals and foreigners.

And so we come full circle. What was once a gateway for Japanese people to experience Western life has, over time, evolved into a way for Westerners to experience a part of Japanese life. Indeed, doing a quick Google search of the phrase “traditional kissaten” today will give you pages and pages of articles listing kissaten recommendations for tourists to visit and have a coffee experience that is classically Japanese. Although Western influence will likely remain an inextricable part of the Japanese coffee scene for the foreseeable future, the coffee shop itself as a place of cultural exchange has taken quite a turn, as it now serves as an exemplar of the Japanese way of living. So, whether you’re a coffee aficionado or someone who likes learning about Japan, next time you get a chance, head over to an old-school kissaten to get a sip of Japanese history unlike you’ve ever had before.

Misha is a third-year ALT based in Hyogo Prefecture. When they’re not in the classroom, they enjoy spending their time doing kyudo, visiting shrines and temples and, of course, going to all sorts of cafes near and far. Though a majority of their writing has been in the sciences, they do enjoy branching out every now and then, and have most recently launched a website where you can find more of their work.

Works Cited:

- Merry White. 2012. Coffee Life in Japan. Berkeley. University of California Press.

- Claire A. Williamson. 2017. A Coffee-Scented Space: Historical, Cultural, and Social Impacts of the Japanese Kissaten. Student work. Yale University.

- Megan Macasaet. 2021. A Penny For Your Cuppa: How Coffeehouses Revolutionized Coffee Consumption in England’s Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Constellations 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.29173/cons29433.

- Anastasia Widyaningsih, Putri Kusumawardhani, Diana Zerlina. 2021. Coffee Culture and Urban Settings: Locating Third Place in the Digital Era. The Cases of About Life Coffee Brewers in Tokyo and Kopi Tuku in Jakarta. Proceedings of the ARTEPOLIS 8. https://doi.org/10.2991/assehr.k.211126.014

- Helena Grishpun. 2012. Sipping Culture: Coffee and Public Space in Japan and in Israel. Conference Proceeding 2012 vol. 1. Israeli Association for Japanese Studies.

- Elise K. Tipton. 2001. Rectifying Public Morals in Interwar Japan. Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies, Vol. 5 (2).

- Olga Kwaczyńska. 2020. The Reception of American Jazz in Japan: An Outline of Issues. Kwartalnik Młodych Muzykologów UJ.

- Sabukaru. Japan’s Past and Present: An Introduction to Kissaten Culture. Jan 10th, 2024.

- Tokyo Weekender. 2022. Millennials and Gen Z-ers Behind Japan’s Latest Kissaten Revival. Jan 10th, 2024.