A Celebration of Re-Imagined Spaces

Holly Walder (Gunma)

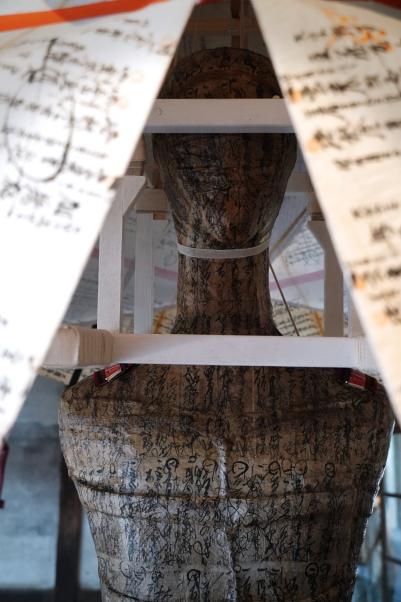

The Nakanojo Biennale is a uniquely immersive international contemporary art festival that takes place spread across five areas of the mountain community of Nakanojo town, Gunma Prefecture for a month in September every two years. This year the theme was “Cosmographia”—named for the encyclopaedic work by German cartographer Sebastian Munster in the 16th century. This choice elicits comparison between Sebastian Munster’s world and our world in the 21st century. Without accurate measuring equipment, and much of the world still unexplored, such encyclopaedias were built from the imagination as much as real people and places. While we can now make accurate maps, the boundaries of our world have been confused by technological advancement, climate change, pandemics, war, economic recession, and the vast swathes of information that we have at our fingertips in the digital age. This year was my first visit to Nakanojo Biennale. Apart from browsing the main website, I chose to go in blind so my reaction would be based solely on my impression of the work and information I was presented with at the moment.

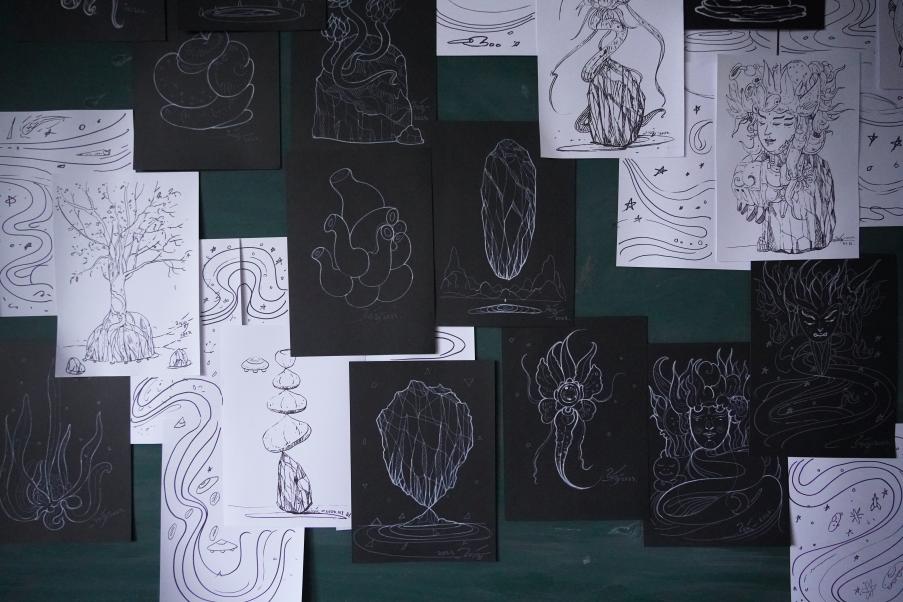

The genius of the Nakanojo Biennale is plain to see. The benefit for the town is clear. Many small towns like Nakanojo are now seeking to find ways to attract new visitors and residents in the face of economic stagnation and a falling birth rate. Not only is it an excellent way to repurpose otherwise disused spaces, but by spreading the festival across the wider town area, it encourages visitors to discover things they will want to revisit. It is also a great opportunity for an artist residency. It offers the relative peace and seclusion of being in the mountains and is particularly good for international artists. Using the whole of Nakanojo as a playground frees the art from the confines of the traditional museum experience of vases in glass boxes in austere empty rooms, and plunges them into the “strange world” that the theme alludes to.

Nakanojo town is not a vessel for the art, but part of it, and the intimate relationship between the resident artists and the town was clear. The link between each piece and the space it occupied felt utterly seamless and natural. Having never seen another piece of art in those same spaces, I find it hard to envision them containing anything different. Even the travel between each area feels like it is part of the festival. The landscape never lets you forget that this is a mountain village, and that life exists here on many overlapping levels. Some of the excursions up steep, narrow single lanes in my little kei car were downright spine-tingling- and it certainly made me appreciate the art I saw up there that much more.

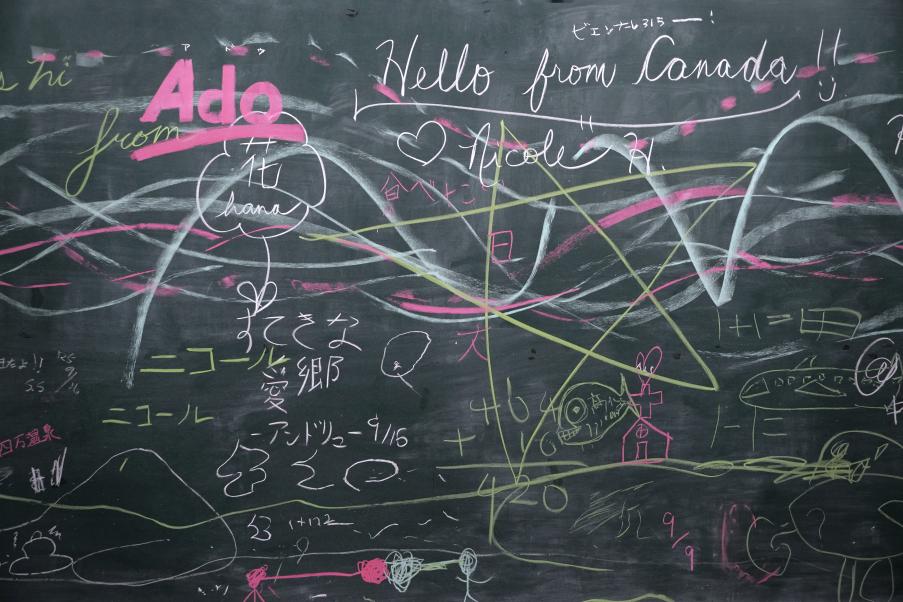

As I passed from one exhibit to another, I couldn’t help but marvel at the at-times dystopian feel of these reimagined spaces. I was reminded of the high street in my own hometown, filled with charity shops, takeaways, and boarded-up storefronts. It is like witnessing the long, drawn-out death of a community—rather depressing. But this is not the case in Nakanojo’s old schoolhouses, empty shops, and gutted bathrooms. Ordinary, purposeful spaces. While the art re-envision the spaces, their previous functions are never forgotten or ignored.

As I gingerly made my way up those steep slopes, I thought about the many elementary school students that had trudged their way up the hill over the years, with their bags overladen with books. Inside the schools, I noticed the worn wooden benches, faded photographs and un-ticked clocks. All the desks, chairs and books that were once intricately sewn into the fabric of everyday life in this mountain town were now stacked up in corridors to make way for the new life that the festival breathes into the town. Moved, but still there. In spite of their functional obsolescence, these objects and spaces don’t stop existing. In a sense, the very obsolescence of an object gives birth to its new purpose—to remind us of the shortness of human memory; permanent evidence of the temporality of everyday life.

Why is it that the things that were once so mundane and insignificant, become the most significant once they have fallen out of use? It is a quirk of human memory that the things you do the most often are the things that you forget the fastest. Each new iteration of the event overwrites the previous, so while you might have lots of memories of exciting weekend outings, you may have little to no memory of your morning routine and what you ate for breakfast. Maybe this is why glimpses of the everyday things that you forgot bring up the most emotion and nostalgia.

As an amateur street photographer, I am deeply fascinated by the blurring of the ordinary and extraordinary wrought by the passage of time. When I first picked up my camera with the intention of trying to preserve some of the essence of ordinary life, a few people asked me why I bother. Sometimes my requests for a photo of friends and family would be met with audible groans. Why do you need a photo of this? There’s nothing special about it. And yet, that is why there must be a photo of it. As the months, years, and decades pass, the once mundane photos become ever more interesting. One day, they’ll see the photo they groaned about and think “Wow! Look at our old TV! The screen was so small!,” “I wore that t-shirt so much, I loved it!,” “I don’t remember the walls being that colour.” Of course, I don’t take a photo of absolutely everything I do—it is inevitable that some things are lost to time—but I think it is important to keep snippets of the ordinary in some way, be that through photography, a journal, or an old family recipe. Those snippets are what make culture and beloved tradition. Do something to remember your bedroom (as you live in it now; not made beautiful for the sake of a photo), your dinners on a weeknight, the video game that you played for hours every day one summer. It might not end up in a museum of times passed, but one day you’ll be glad to remember it.

Nakanojo Biennale is an unmissable part of the art calendar. There are so many exhibits and events happening throughout the month that every visit promises to be an entirely unique experience. I only managed to see the Isama, Shima, and main town areas when I was there, and I am eager to revisit if I ever have the privilege. I recommend going in blind as I did to find new experiences and ideas around every corner.

Holly Walder is a second-year ALT in Gunma Prefecture, and the Fashion Editor of CONNECT. Her favourite type of art is the kind you find in the everyday when you aren’t looking for it.