This article originally appeared in the October 2023 article of Connect.

Dylan O’Connell (Hyogo)

About one hour northwest of Kobe via the Kobe Electric Railway is the small suburban city of Ono. A traditional manufacturing hub of the Japanese abacus known as the soroban, Ono exhibits its pride by being home to the world’s largest abacus.

About one hour northwest of Kobe via the Kobe Electric Railway is the small suburban city of Ono. A traditional manufacturing hub of the Japanese abacus known as the soroban, Ono exhibits its pride by being home to the world’s largest abacus.

Although relatively rural, Ono has many more tourist attractions that punch above their weight. In spring, the Ono Sakura Corridor blooms along the Kakogawa River with nighttime illumination. Similarly, the nearby Sunflower Hill Park’s almost 380,000 sunflowers bloom in early summer with cosmos taking their place in autumn. Finally, the nearby temple of Joudo-ji houses some important cultural properties and a variety of hydrangeas. (1) However, undoubtedly superseding all these attractions is the 小野まつり (Ono Matsuri), the largest festival in Kita-Harima with about 140,000 attendees. (2) Last year was my first time going and I could not have imagined that this year, I would not only be attending, but also participating in dancing on stage.

The Ono Festival primarily involves dance performances on three stages divided between two days. The first day features dances by groups of citizens from the various wards of the city; this is what I participated in. The second day, referred to as the おの恋おどり (Ono Koi Odori) Festival, is a competition featuring dances by professional groups from around Hyogo and sometimes larger Japan. The name “Ono Koi Odori” carries a delightful double meaning: come to Ono and fall in love with it. (3) Experiencing the festival makes it very easy for one to do so.

I anticipated attending the Ono Festival months in advance with my friends who lived there. Through them, I was invited to join in representing their ward by participating in a citizen’s dance called 市民総踊り (Shiminsouodori) on stage. So, about three weeks before the festival, I attended my first and only dance practice.

I anticipated attending the Ono Festival months in advance with my friends who lived there. Through them, I was invited to join in representing their ward by participating in a citizen’s dance called 市民総踊り (Shiminsouodori) on stage. So, about three weeks before the festival, I attended my first and only dance practice.

Arriving before my friends, I was struck by how welcoming the older Japanese locals were. There I was, a foreign nonresident of their city who was absent for two weeks of practice and would be absent for two more, but it felt as if I were a close friend. A Japanese English teacher guided me through sign-in and I spoke with a kyuudou (Japanese archery) teacher before my friends came. After everyone arrived, including more foreigners and parents with children, practice began.

There were two dances: the first, a traditional bon dance that may be seen around Japan; the second, a local dance to a local song. Contrary to the testimony of my friends, the dances were easy to pick up and learn by watching others. The bon dance was slower and more methodical than the energetic local dance, but once the pattern of moves was memorized, all one had to do was repeat them to the music of 令和音頭 (Reiwa Ondo) and ずっとおの恋 (Zutto Ono Koi) respectively. Everyone was a novice and laughed as they made mistakes or as children ran between our legs. This contributed to an atmosphere that was pleasant and communal, aiding the ease of learning and becoming comfortable with the dances.

With a smile, I waved my arms like sunflowers in the breeze. I swept them into a large circle above my head and kicked up my leg as if my body was the sunflower itself.

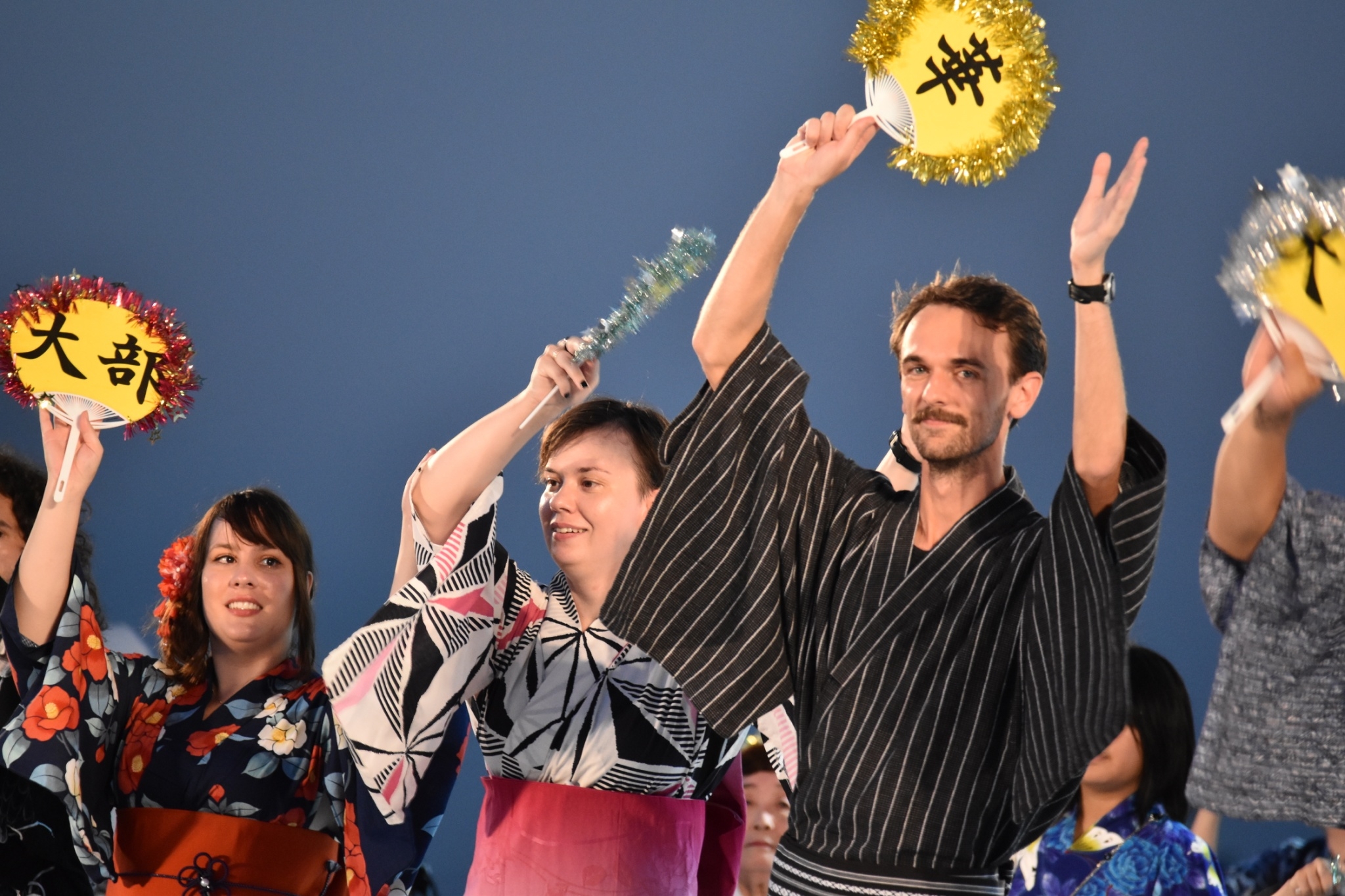

Weeks later, it was time for the festival performance. I tried to privately practice the dance during my absence, but I was a little rusty. Thankfully, before performing on stage, we would all meet and do it once more. My friends and I arrived at the community center early with our yukata in possession. The men were first to be directed towards a tatami room in the back. An elderly woman there assisted us in adorning our traditional wear better than we could have done ourselves. My friends and I presented a variety of colors and patterns, but other people in the troupe had matching yukata. I learned that some patterns represented their neighborhood where they had lived for decades. The idea of representing not just a ward in the city, but also an individual neighborhood on stage was wonderful. When everyone was dressed, we practiced for the final time. The steps returned with ease, feeling more natural with a flowing yukata and decorated gold uchiwa fan in hand.

Weeks later, it was time for the festival performance. I tried to privately practice the dance during my absence, but I was a little rusty. Thankfully, before performing on stage, we would all meet and do it once more. My friends and I arrived at the community center early with our yukata in possession. The men were first to be directed towards a tatami room in the back. An elderly woman there assisted us in adorning our traditional wear better than we could have done ourselves. My friends and I presented a variety of colors and patterns, but other people in the troupe had matching yukata. I learned that some patterns represented their neighborhood where they had lived for decades. The idea of representing not just a ward in the city, but also an individual neighborhood on stage was wonderful. When everyone was dressed, we practiced for the final time. The steps returned with ease, feeling more natural with a flowing yukata and decorated gold uchiwa fan in hand.

From the community center, we walked to the site of the festival. On approach, we could hear music from other performances and noise from the crowds carrying across the sunset-lit rice paddies. We waited backstage, combatting the heat by soaking in cool water being sprayed by large fans. Countless group photos were taken with excited smiles belying an underlying anxiety. My chest tightened in anticipation. Curiously, the group performing prior to us also performed the Zutto Ono Koi that we were to do as our second dance. That became a recurring theme of the festival: Zutto Ono Koi being danced by many different teams. Before long, it was our turn to go on stage.

Beckoned by the hosts, we walked on stage and formed two concentric circles afore five men carrying flower shaped signs spelling the message 大部の華2023 (Obenohana). 大部 (Obe) is the name of the ward, so the phrase roughly translates to “Obe’s splendor.” Because the troupe organizers wanted the foreigners on display, we started at the front of the outer circle. I was nervous but comforted by the sight of familiar faces in the audience and confidence in my own knowledge of the steps. The dance began awkwardly as our spacing was a little off and synchronizing the initial steps with the subtle notes of the song was always difficult, but we quickly entered our groove and moved our way around the circle. Being in the outer circle also yielded the benefit of being able to view those in the inner circle and match their timing. I think almost everyone on stage was using someone else as a point of reference, with no one considering themselves the leader or an expert. Regardless of our individual and collective confidence, the dance went well, and we repositioned ourselves for the second.

Switching from two circles to multiple lines of people directly facing the audience, I found myself front and center on stage. Next to me was the teacher who had initially guided me when I arrived at my first practice. He appeared drenched in sweat and was barefoot, a sight which was oddly comforting. We weren’t like the professional teams that would perform that evening and again the next day, we were just average people. That helped me relax and embrace the energy of the second dance to Zutto Ono Koi.

Switching from two circles to multiple lines of people directly facing the audience, I found myself front and center on stage. Next to me was the teacher who had initially guided me when I arrived at my first practice. He appeared drenched in sweat and was barefoot, a sight which was oddly comforting. We weren’t like the professional teams that would perform that evening and again the next day, we were just average people. That helped me relax and embrace the energy of the second dance to Zutto Ono Koi.

With a smile, I waved my arms like sunflowers in the breeze. I swept them into a large circle above my head and kicked up my leg as if my body was the sunflower itself. I never looked at my fellow dancers on stage, only the audience, among whom were friends tempting me to laughter as they mimicked our moves. Although the song was short, dancing on stage I experienced a form of time dilation. Minutes stretched into hours that unfolded in seconds. When the song stopped and we held our final poses, I only wished there were more for us to show, another performance to present. But it was over, and we walked off stage to refreshing cups of water and congratulations.

The rest of the Ono Festival was also wonderful. This year, there were 93 dance teams from all over the prefecture. The victorious team was bestowed a prize by the mayor of Ono’s sister city Lindsay, California and an ambassador from the Miss Oriental beauty pageant. The presence of this fellow American, as well as the initial inclusion of my friends and I dancing on stage, seemed to represent the city’s commitment to cultural exchange.

In corresponding with the Ono City Tourism Division regarding Zutto Ono Koi, I learned it was written for the 40th festival. The lyrics of Zutto Ono Koi paint an impression of the Ono Festival that matches my own experience: yukata lined up at stalls, a hot summer night, limitless dancing, and fireworks. Those on stage will forget the time as they dance and sing to their heart’s content with their friends. (4) The song itself describes my experience on stage. However, a second and faster choreographed dance exists to a slightly sped up version of the song. Before the fireworks on both nights, members from many of the dance teams crowded the stage and performed the fast version. The final performance on the final night was accompanied by confetti, flames, and fireworks. Perhaps next year, I can learn and dance to that version of the dance too, and form another integral memory in my life.

Dylan O’Connell is a third-year ALT from the U.S. who is currently working at two senior high schools in Kita-Harima. A film studies graduate, he is enamored with Japanese culture and is often finding peace at shrines. When not on a pilgrimage, he can be found studying Japanese or writing in the comfort of his small town. He also likes occasionally writing on his blog Dylan O’Connell’s Writing Corner

![CONNECT ART ISSUE 2024 SUBMISSIONS [CLOSED]](http://connect.ajet.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ARTISSUE-INSTA-600x500.png)