This article is a web original.

Marco Cian (Hyogo)

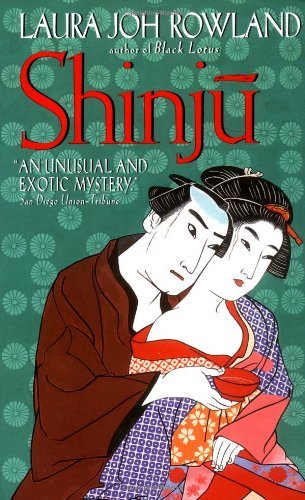

Japan has a long history of combining the jidai geki (period drama) and mystery genres together. Indeed, there’s a word specifically for stories in this crossed genre: torimonocho. However, to the best of my knowledge Laura Joh Rowland was not influenced by torimonocho when crafting her own Edo period detective, Sano Ichiro, if for no other reason than the fact that these works still remain largely untranslated today, and would almost certainly have been inaccessible in the 90s when Rowland first conceived of Shinju, the first book in the Sano Ichiro series.

No, if there was any influence to Rowland’s work, it seems to be her own personal love of mysteries, combined with the historical doorstopper wave that was still riding high in the 90s.¹ Like those beefy historical fiction paperbacks that once lined bookstores in droves (and are now mostly found at your local Goodwill), part of the appeal of Shinju is its purported educational value. Rowland will often pause proceedings to detail some piece of historical or cultural trivia, which can get annoying sometimes, though it never properly broke the story for me. And, just like those tattered paperbacks, Rowland will sometimes present trivia that isn’t actually true².

However, Shinju differs from its contemporary historical fiction bestsellers in several important ways, which I think allow it to rise above the dross and remain a thrilling read. Firstly, it’s significantly shorter than most books of that time and genre. My copy was only 367 pages, which may not seem that short, but is practically a novella compared to something like Gai-Jin, which had come out the previous year. Even with the trivia explanations, Rowland does her best not to waste your time with paragraphs and paragraphs of irrelevent information. Secondly, there’s only one love scene in the whole book, and it’s remarkably tasteful. This may not seem that noteworthy, but you have to remember that the other main selling point of historical doorstoppers back then was the “exotic” love scenes that were often described in copious detail³.

Thirdly and most importantly though, Rowland never loses sight of her end goal, that being to tell a thrilling mystery. Shinju may be longer than an Agatha Christie novel, but this is because it’s a lot meatier than a standard whodunnit, with well-crafted red herrings, political conspiracies, and character arcs and growth. Rowland may pester you with trivia, but she never wastes your time with characters sitting around and talking for pages and pages. She’s much more interested in demonstrating history through her characters’ actions than having characters tell each other (and the reader) these details at length. While I cannot wait to read the sequel to Shinju, I think the story stands well on its own, and I would heartily recommend it to anyone who likes political thrillers, historical fiction, or even just a good mystery.

[1] To give a basic idea of what the standard for historical fiction at that time looked like, you can check out this review of one of its most famous authors, Gary Jennings. Fair warning though, the content can be rather gruesome and nasty.

[2] The most notable example is Rowland coming up with this elaborate backstory to explain Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s building of dog shelters and adoption of several canines, which involves ancient prophecies and the Chinese zodiac. In reality, anyone here will tell you that Tsunayoshi’s reasons for this were simply that yer man really liked dogs.

[3] People have debated for years as to why the genre died out, but I think a major factor was the internet allowing people to find more stimulating forms of entertainment. If you catch my meaning.

1 thought on “A Shogunate Era Sherlock”

Comments are closed.