This article originally appeared in the November 2022 issue of CONNECT.

Sophia Maas (Saga)

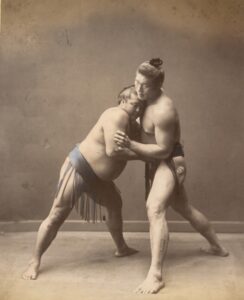

How much do you know about Japan’s national sport? I’m sure you’re familiar with the evocative images of large men in nothing but a mawashi (belt) standing off against each other in a dohyō (ring), but that’s not all there is to the sport. Sumo has a rich history that began centuries ago and still persists strongly today.

History of Sumo

Though it is highly regulated now, sumo did not start as a sport with many strict rules. In fact, it didn’t start as a sport at all. Some say that the first written record of sumo appears in one of the oldest surviving Japanese texts. The Kokiji, or Record of Ancient Matters, talks about the first sumo match between two gods, Takeminakata and Takemikazuchi. However, Nomino Sukune, a legendary figure in Japanese history, is generally credited with originating the sport during the reign of Emperor Suinin (29 BCE-70 CE). Regardless of the specific origins, sumo would persist in early Japanese history as a Shinto ritual, mostly at shrines or in court.

Though it is highly regulated now, sumo did not start as a sport with many strict rules. In fact, it didn’t start as a sport at all. Some say that the first written record of sumo appears in one of the oldest surviving Japanese texts. The Kokiji, or Record of Ancient Matters, talks about the first sumo match between two gods, Takeminakata and Takemikazuchi. However, Nomino Sukune, a legendary figure in Japanese history, is generally credited with originating the sport during the reign of Emperor Suinin (29 BCE-70 CE). Regardless of the specific origins, sumo would persist in early Japanese history as a Shinto ritual, mostly at shrines or in court.

Sumo remained a ritual practice, typically initiated by the ruling class, until the Sengoku period (1467-1600) when public fights came into existence. The public bouts tended to be bloodier and more brutal than their more formal counterparts, leading to a decree to shortly ban public sumo matches. Sumo soon returned with the first sanctioned match occurring in 1684 at Tomioka Hachiman Shrine. With this sanction, many of the rules and traditions that still occur in modern sumo were established.

Sumo Rituals

Because of its ancient origins, Japanese tradition and Shinto ritual have been emphasised and oftentimes publicised to garner support and interest in the sport. Japan’s national sport has earned its name by being a veritable time capsule that allows us in modern times to look back at certain aspects of Japanese history. If you’ve watched a sumo match, you’ve certainly noticed the specific way the gyōji (referee) dresses, or maybe you arrived early enough to watch the dohyō be built. Almost every aspect of sumo, from training to finishing a fight, is done with purpose in accordance with the traditions that remain preserved today.

Because of its ancient origins, Japanese tradition and Shinto ritual have been emphasised and oftentimes publicised to garner support and interest in the sport. Japan’s national sport has earned its name by being a veritable time capsule that allows us in modern times to look back at certain aspects of Japanese history. If you’ve watched a sumo match, you’ve certainly noticed the specific way the gyōji (referee) dresses, or maybe you arrived early enough to watch the dohyō be built. Almost every aspect of sumo, from training to finishing a fight, is done with purpose in accordance with the traditions that remain preserved today.

Sumo wrestlers are trained in a heya (stable) and live their days according to highly regimented schedules. The wrestlers will typically wake around six in the morning (though some wake later in the day, depending on their rank), and convene for lunch around 11 o’clock. Sumo wrestlers must eat meals of a dish called chanko-nabe, a calorie-rich stew that is eaten in large quantities to increase weight. After this lunch, they will take a long nap, which is meant to help them absorb nutrients and calories from their meal. Individual schedules after this may change depending on the ranking of the wrestler. All this is, of course, in preparation for their official matches.

Before a match can begin, or even think about beginning, a dohyō must be built. Traditionally, this is a 4.55-metre raised platform made of clay. The day before a tournament the dohyō is “cleansed” by placing a series of items, including salt, cleansed rice, and a dried chestnut, into a hole in the centre of the ring. Then, the match can begin. Well. . . not quite yet. When the fighters appear for a match, the gyōji dressed in traditional garb and the wrestlers themselves in nothing but a mawashi, several other cleansing rituals must take place.

Maybe you have seen sumo wrestlers perform a shiko, the movement of raising a leg and slamming down onto the ring. This is done with the intent to crush lingering malign spirits. With this ritual completed, the wrestlers cleanse themselves with chikara-mizu (literally translated to mean “strength-water”). If you have entered a shrine or a temple (not during COVID-19 times!), perhaps you have performed something similar—it is the action of taking a wooden ladle full of water and swishing it around in your mouth. The next ritual signals that the fighters are about to enter the ring for their fight. With a handful of cleansing salt thrown into the ring, they are ready to fight.

Maybe you have seen sumo wrestlers perform a shiko, the movement of raising a leg and slamming down onto the ring. This is done with the intent to crush lingering malign spirits. With this ritual completed, the wrestlers cleanse themselves with chikara-mizu (literally translated to mean “strength-water”). If you have entered a shrine or a temple (not during COVID-19 times!), perhaps you have performed something similar—it is the action of taking a wooden ladle full of water and swishing it around in your mouth. The next ritual signals that the fighters are about to enter the ring for their fight. With a handful of cleansing salt thrown into the ring, they are ready to fight.

The fights themselves are very, very short. In fact, most are less than 30 seconds. Many spectators will arrive early to watch the spectacle of the ritual being performed, marking sumo’s tradition as a major draw for some fans.

The ranking systems and prestige offered to sumo wrestlers are complicated and multi-tiered. The specifics of the wrestlers in the ring, their regulated moves, and catalogued winning techniques are vastly interesting and have their own origins in Japanese history. If you are interested in learning more about Japan’s national sport, you can plan a trip to Tokyo’s Sumo Museum, a place dedicated to gathering and preserving old sumo relics, such as bankuze (official ranking list) and the ceremonial aprons worn by the fighters.

Sophia Maas is a first-year ALT currently living in Saga prefecture. Their current hobbies are exploring their city by bike and participating in as many community cooking events as possible.