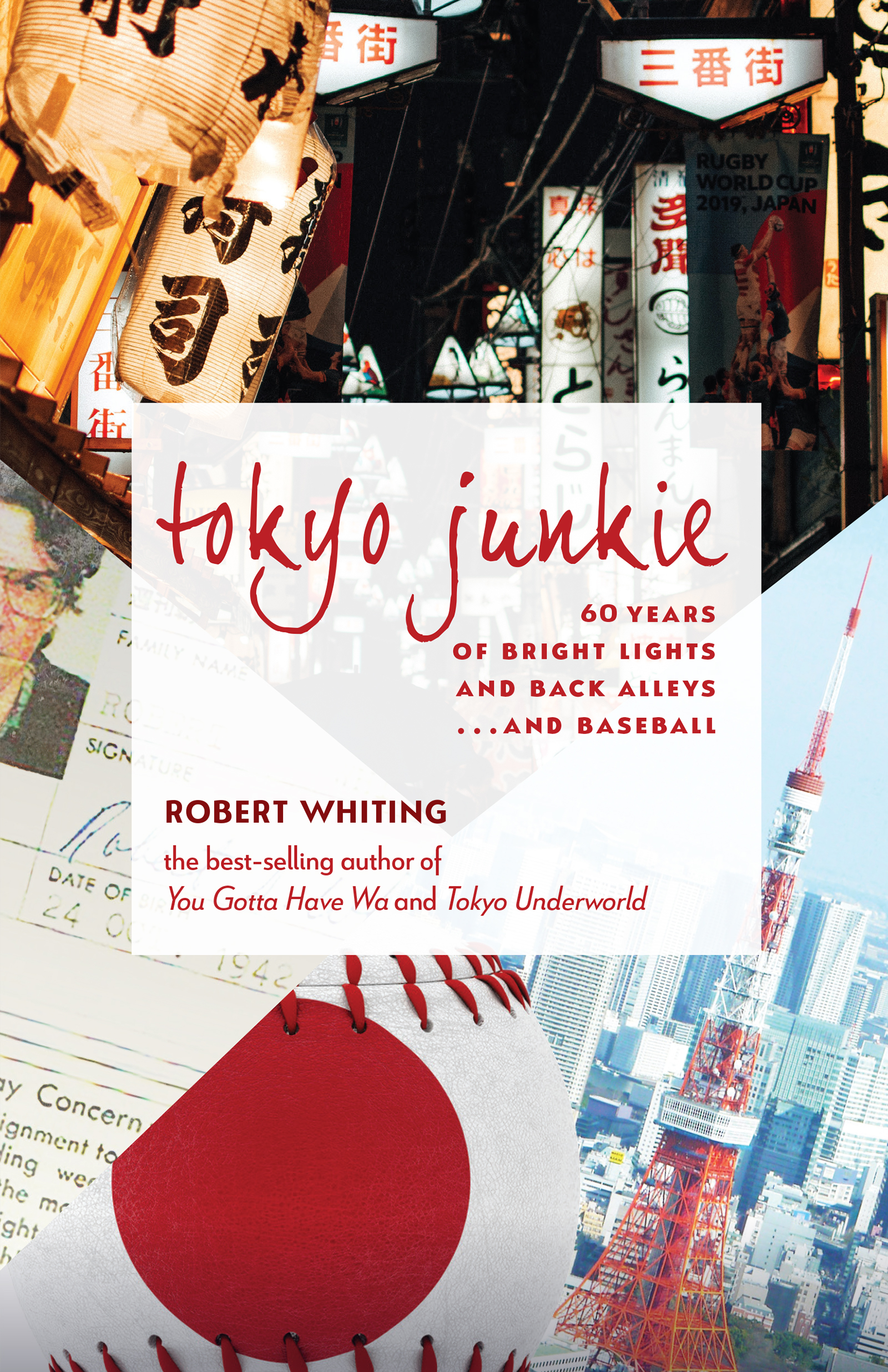

A review of Robert Whiting’s Tokyo junkie.

This article originally featured in the April 2021 issue of Connect.

by Kayla Francis (Tōkyō)

I first stumbled across Robert Whiting’s work when I visited a bachelor pad in the middle of Yoyogi. Tokyo Underworld lay lonely on the coffee table, its spine indicating that it had never been read. Unable to resist any book, I found myself reading it every time I went there—an unread book is, after all, the worst kind of crime. Detailing the criminal underbelly of Tōkyō after the occupation in WW2, Tokyo Underworld gripped me from the start. It read like a seductive James Bond novel but more thrilling—why? Because everything is true. It’s sexy, action-packed, morbid and sometimes downright dirty. Long after I stopped visiting that apartment I thought about that book—alas, that’s the fate of all the books I never get to finish.

When I got the opportunity to read Tokyo Junkie, Whiting’s memoir on living in Tōkyō for the past 60 years, I was excited but also a little hesitant. Would it be anywhere near as interesting as Tokyo Underworld? Who exactly is Robert Whiting and why should we be interested in his life?

Robert Whiting is a very successful journalist and author whose work has noticeably been featured in The Japan Times, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated, Smithsonian, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, Time, and many other celebrated publications(1). His book You Gotta Have Wa (on baseball in Japan) reached fame both in Japan and internationally. He has written on various topics, including sports, Tōkyō nightlife, and crime. He is also one of the only Western writers to regularly write in a Japanese column.

Robert Whiting is a very successful journalist and author whose work has noticeably been featured in The Japan Times, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated, Smithsonian, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report, Time, and many other celebrated publications(1). His book You Gotta Have Wa (on baseball in Japan) reached fame both in Japan and internationally. He has written on various topics, including sports, Tōkyō nightlife, and crime. He is also one of the only Western writers to regularly write in a Japanese column.

If you loved anything written by the late Anthony Bourdain, notably Kitchen Confidential then you will probably love this. Whiting does a great job of making his life beguiling, even in some of the most unfortunate circumstances you can’t help but wish to be in the adventure with him. His memoir takes you on a journey into how he got the jobs he had and his experience living in Tōkyō during the 1964 Olympics, the economic boom, the following crash, and up to the coronavirus today.

Whiting has been noticeably remark-able for his work on documenting the impact that the 1964 Tōkyō Olympics had on Japan(2). Not just in regards to the economy (though it had a very large impact indeed) but also concerning the culture and mindset of Japan. It was highly fascinating reading the accounts of the 1964 Olympics because so much of it is also relevant today.

I was lucky enough to move here a year before the Olympics were expected to be held (before it was inevitably postponed) which meant a lot of buildings were being built and opened to celebrate and account for the huge influx of expected tourists. Shibuya

noticeably changed with the opening of Shibuya Scramble Square and Miyashita Park.

When the memoir reaches the 2020 games themselves it exposes the reality, “Right from the start preparations were plagued by embarrassing cost overruns, ineffective leadership, finger-pointing at all levels, and widespread doubts that a seemingly inept government would have everything ready in time.”

Whiting’s accounts of interviewing prominent athletes (such as Daryl Spencer, Clyde Wright, Richard Beyer “the Destroyer”, Reggie Smith, and many more), the issues the athletes faced living in Tōkyō, the trouble Whiting went through to tell their stories and the reality of what goes on in the training field all prove that Whiting’s memoir is fascinating, funny, and scarily relevant to modern Tōkyōites.

So what has this book got to do with baseball? As well as being an acclaimed sports journalist and the author of You Gotta Have Wa, a book considered a “definitive text on Japanese culture seen through the lens of sport”(3), for Whiting, it was baseball that “gave [him his] first true connection to Japan and its people” and it helped the book with its most import-ant aspect, its relatability: “Japanese baseball . . . was the only thing I could remotely under-stand on Japanese tele-vision. Many of the words were English derivatives: sutoraiku (strike), boru (ball), kabu (curve), homu ran (home run) . . . etc. You get the idea.” What foreigner hasn’t gotten excited upon realising that they understand katakana words?

This is emphasised by his obsession for Kyojin no Hoshi which he watched “every Saturday evening.” Though Whiting had “mixed emotions” about the series, it helped steer his mindset away from American baseball, “as the Japanese said, there was beauty in suffering and in Kyojin no Hoshi the suffering was so beautiful—because of the love behind it—that it made you want to cry.”

It is also through baseball that Whiting cleverly dissects both American and Japanese culture.

“Baseball provided a window into the culture, the national character—if there is such a thing—and on the values and assumptions that divide the Japanese version of the game from ours.”

“Baseball became a symbol of Japan’s determination to catch up with the more industrially advanced West, using the same model of dedication, or magokoro as they called it, and discipline.”

By watching baseball and baseball-related animes, Whiting was able to find a sense of belonging in Tōkyō, “For a large chunk of the population, watching the Major League games in the early morning—as early, sometimes as 4 or 5 a.m.—before going to work became the norm. Some twenty-five million people watched Ichiro break the single-season hits record in 2003.”

This doesn’t mean that it was a walk in the ‘ball’ park—often, it was far from it. Whiting uses his book to showcase the issues of corruption and racism that are still prevalent in modern-day Tōkyō. I was completely oblivious to the challenges that journalists in Japan face.

“Under the Giant’s restrictive system, players were not allowed to do sit-down interviews with reporters without explicit permission from the front office, or without a substantial fee paid to the team for the privilege. It was a notable departure from the way things were done in the United States.”

This is nothing compared to the political corruption within the sports industry and the government that Whiting also discusses in his memoir.

This doesn’t mean that I agree with everything he writes. Whiting often discusses how easy it is for foreign men to get involved with Japanese women; while this is a stereotype stemming from the fetishisation of Asian women and the male gaze, there are times when he rightly states that, “Today’s more independent and liberated women might understandably take offence at the above account, related here solely in the interest of accurate reporting.” However, this has very little to do with reporting and everything to do with the fact that sex, well—it still sells. After all, why else would you need to tell us about the “young females in hot pants” selling Kirin beer at baseball games?

That aside, Tokyo Junkie doesn’t just serve as a memoir, it’s witty, shocking, entertaining and educational. This is the kind of book that you can read repeatedly and still learn something new about Tōkyō. After reading it, I also caught myself staring at the older generation on my daily commute. The book gave me an appreciation for them and their untold stories. I found myself wondering who they had been before they donned their corporate suits and decided to lead a traditional life.

Despite his unbelievably large body of work, it doesn’t seem like we’ve heard the last of Robert Whiting.

“More importantly, work keeps coming over the transom and there are many more subjects that lure me on to explore and write about. Life here is a continual reminder that there is still much left for me to do.”

I look forward to his next book.

Tokyo Junkie will be available from April 20, 2021.

Kayla Francis is a Tōkyō JET from London, UK. She is also CONNECT’s Sports Editor. When she is not cooking and eating too much, she can be found reading or staring at her yoga mat.