Lush Nature, Unforgettable Food, and Lessons from Disaster

This article originally featured in the September 2020 issue of Connect.

Anna Thomas (Shibata Town, Miyagi Prefecture)

In 2015, I got word of a new 1000 km long-distance hiking course being made in Tohoku. Tohoku’s Pacific coast was seriously damaged by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that caused the death of almost 20,000 people, and this “Michinoku Coastal Trail” was created to attract people to the coastline to enjoy its nature, history, culture and cuisine, as well as to meet local people and learn about natural disasters. Previously, I’d spent most of my time at the coast as a post-tsunami volunteer, but this was my chance to enjoy these areas as a tourist! I’ve hiked bits and pieces over the years, and in this past year, I’ve section-hiked 700 km of the trail. I’ve done English translations for the MCT for years and now work part-time at the trail’s headquarters in Natori, Miyagi. In short, I love this trail, and I’m here to invite you to come when you can and enjoy it for yourself.

“Hiking this trail has been more about becoming comfortable with who I am already and working within my limits.”

GIFTS THE MCT HAS GIVEN ME

When I started section-hiking the trail, I expected a journey to “find myself” and push beyond my limits, but I found that that was not necessarily what was on offer. Hiking this trail has been more about becoming comfortable with who I am already and working within my limits. I am the same person I was when I started my journey, with a couple of extra tools up my sleeve.

One tool is camping. I had never expected to even tolerate camping. In fact, my first night camping on the MCT was miserable. It rained all night. I lived on nuts and bread because I had expected a campground store that wasn’t there. In the morning, I flung my sleeping bag across the empty campground in frustration because it wouldn’t fit back into the microscopic bag it came from. Now, I’ve grown to love it. With a tent, you sleep in the open air, hearing the sounds of waves, ducks having an evening quack, or the occasional shrieking deer, and yet you’re protected from the less pleasant parts of the outdoors like mosquitoes and rain.

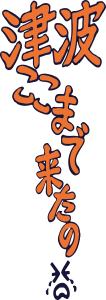

Another tool I gained on the trail may someday help save my life. It was the accumulated effect of what we’d heard about the 2011 tsunami that led my husband and I to evacuate to higher ground during Typhoon 19 last year. At the time, I wanted to deny there was an emergency, to believe that our area was safe because it had never seriously flooded before. Those thoughts reminded me of stories we’d heard on the coast, and I remembered the moral of all those stories: we needed to err on the safe side and act to save ourselves now. Possibly we would feel foolish later, but feeling foolish is always better than dying. (Our apartment suffered no damage, but we made the right choice. Some houses in our area were flooded past the first floor.)

WHAT BRINGS ME BACK

Senkaen in Rikuzentakata

While I’ve benefited a lot from the trail as a person, I don’t return again and again for an ongoing education in disaster safety.

I go because it’s pretty. About a quarter of the trail goes through a national park called Sanriku Fukko (Reconstruction) National Park. The iconic scenery of this area includes jagged rocks, turquoise blue waters, and green pines along the zigzag coastline. The trail also goes through a variety of other landscapes: tranquil rows of houses with knickknacks and potted plants, vast flat fields, thick forests, and mysterious misty islands.

I go for the food and the hot springs. I regularly have intrusive daydreams about this octopus rice bowl and crepe lunch I had in Rikuzentakata. Once, I had this boiled crab that was so good that part way through eating it not only did I completely forget about table manners, but I also stopped caring whether or not I was eating the shell. Usually, after a hike I’m hungry enough that eating a cardboard box would probably taste

good, so having top-shelf seafood washed down by some cold beer? Absolute heaven.

I go for the people. The old fellows managing the campgrounds I stayed at were always wordlessly handing me handfuls of candy or cans of juice. In especially outgoing areas, anyone from a construction worker on a break to a gentleman enjoying fishing with his poodle would sidle over to chat about my hike and recommend sights. I’ve also been given a ride in a police car in Onagawa (not that kind of ride!) and a free place to stay in Ofunato.

Finally, I go to witness history: another snapshot in time as Tohoku continues to recover from the tsunami. The barren landscapes of wrecked buildings and hills of rubble I remember from volunteering have already mercifully disappeared and transformed into places with clean sidewalks, restaurants, and train stations. Progress towards recovery continues. Today’s rows of saplings will someday become forests. Bare patches of construction are waiting to become shopping streets, parks or hotels.

SUGGESTED COURSES

As a starting point for planning, here are two courses based on hikes I’ve done. Each one is about a week long, most are under 20 kilometers per day, and the start/end points for each day are either accessible by train/bus or are near several places to stay.

Hachinohe to Kuji

Day 1: Same Station to Oja Station, 19 km

(add an extra two days here to go up Mount Hashikami if you make a reservation at the campground).

Day 2: Oja Station to Taneichi Seaside Park, 10 km.

Day 3: Taneichi Seaside Park to Rikuchu-Noda Station, 22 km.

Day 4: Rikuchu-Noda Station to Kitasamuraihama Campground, 11 km (don’t attempt the river crossing, use the detour).

Day 5: Kitasamuraihama Campground to Kuji Station, 20 km.

Day 6: Kuji Station to Kosode Ama Center, 14 km (return to Kuji Station by bus).

Ofunato to Kesennuma

Day 1: Sanriku Station to Ryori Station, 14 km.

Day 2: Ryori Station to Ryori Station (walk around the peninsula), to Rikuzen-Akazaki Station, 23 km.

Day 3: Rikuzen-Akazaki Station to Goishi Coast Campground, 17 km.

Day 4: Goishi Coast Campground to mid-Hirota Peninsula (stay on the peninsula or take a bus to Otomo Station), 19 km.

Day 5: Mid-Hirota Peninsula to Wakinosawa Station, 19 km.

Day 6: Wakinosawa Station to Karakuwa Sogoshisho-mae Bus Stop, 21 kilometers (bus to a campground or local inn), 21 km.

Day 7: Karakuwa Sogoshisho-mae Bus Stop to Karakuwa Sogoshisho-mae Bus Stop (walk around the peninsula), 20 km.

Day 8: Karakuwa Sogoshisho-mae Bus Stop to Kyukamura Kesennuma Oshima/Kesennuma Oshima Campground in Oshima Island, 14 km.

TIPS

Get the free paper maps.

These are in Japanese, but you can mark them in English as necessary using the online English PDFs. Get the maps sent to you via postal mail to addresses within Japan, or get them in person at the Natori Trail Center and other facilities along the route. New maps should be released in autumn 2020. These will cost money but will be much more durable and contain updated information in Japanese and English.

Decide your schedule.

How much time will you have? What experiences appeal to you? How many kilometers per day will you walk? (Remember: hypothetical kilometers are easier than actual kilometers!) Once you’ve got your general parameters down, contact the Natori Trail Center or connect with other hikers in the unofficial English Facebook group to see which courses would be a good fit.

Arrange your lodging.

An unofficial map showing lodging information is here. This might be one of the most difficult parts of planning since lodging is scarce in some areas. Having trouble? Try basing yourself in cities with more places to stay, like Hachinohe, Kuji, Miyako, Kamaishi and Ishinomaki, and do nearby day hikes. If you prefer camping, you can base yourself at a campground near a train station instead.

Prepare your gear.

At a minimum, this means maps, food and water, hiking clothes, a bear bell, a compass, rain gear, and a cellphone.

Get the downloadable GPS files. Some sections still have little official signage, so along with paper maps and a compass, I highly recommend using the official GPS files with an app. That way, you’ll be able to double-check where the trail route is related to where you are in real-time. For apps, I recommend Gaia GPS, which is free and available for iPhones and Android.

Check Natori Trail Center’s website for advisories.

Don’t skip this step! There are enough detours due to construction or typhoon damage scattered along the trail to throw a wrench into your plans, and many advisories are important for safety. Go to the advisory page and choose the area you plan to visit. You can also look at the detours in map form here.

THE TRAIL ISN’T GOING ANYWHERE

Any time you’re able to visit, the Michinoku Coastal Trail will be here, ready to welcome you with rich nature, kind people, tasty food, and wisdom born from hardship that could change your life!

Anna is originally from Oregon in the United States and has enjoyed life in Tohoku for 10 years. She enjoys knitting, bird watching, programming, and (thanks to the MCT) camping.

Section hiking blog