Laura Pollacco (Kanagawa)

This article originally featured in the November 2018 issue of Connect.

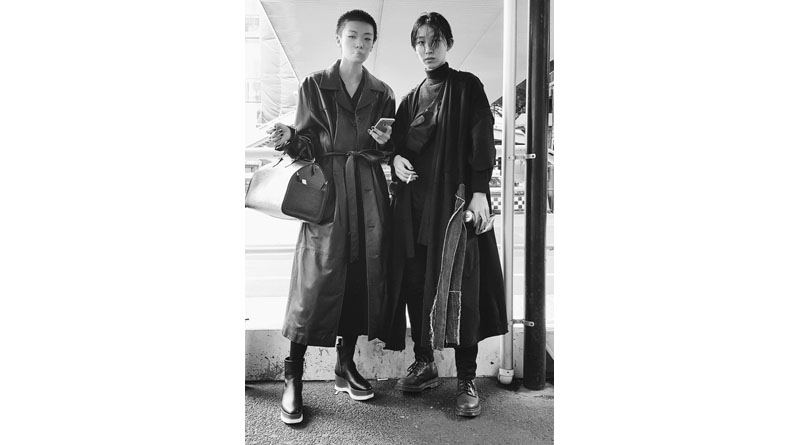

Gender neutral fashion is one of the most talked about ongoing topics in the fashion industry currently. Many articles have covered the cultural shift that we have been seeing over the last seven or so years in an effort to figure out what it is we truly want when we talk about gender neutral fashion, and it’s certainly been a topic that this section of Connect has spotlighted before. Japan is still very conservative when it comes to gender and its views on non-traditional gender identities, but at the same time Japan has a whole fashion subculture which ignores gender entirely. You can certainly see this in the trendier areas of Tokyo. Oversized, boxy silhouettes allow for a blurring of lines between male and female, long loose pieces that adhere to no fixed masculine or feminine form. Western fashion often hails this style as being fashion forward and avant-garde, the West finding itself somewhat behind in this regard. Japan has, however, been leading the way in this trend for a lot longer than many realise.

For almost 50 years, Japan and Japanese designers have had a huge impact on the evolution of genderless fashion in the West. Many fashion historians believe it was a handful of designers from Japan that really showcased how clothes did not need to be designed with gender in mind. It was the arrival of these designers, alarming to some in the industry, that really heralded a new dawn for fashion design and its relation to gender (or in this case, lack of relation).

Rei Kawakuba, Issey Miyake, and Yohji Yamamoto are three designers that really shook things up in the Western fashion scene in the early 1970’s. A fourth designer, Kansai Yamamoto, took his designs to London and thrived in the bright music scene emerging there, forming a great relationship with the singer David Bowie, an androgynous icon at the time. Bringing their avant-garde designs from Japan to Paris, they created controversy by rejecting the idea that clothes should be designed to fit the body. Instead they focused on first creating the garment as a piece independent of the wearer and then allowed the wearer to fit it to themselves.

‘The designs by Kawakubo, Miyake and Yamamoto were known for being gender neutral or unisex. Gender roles are determined only by social rules and regulations formed by society. Clothing constructs and deconstructs gender and gender differences. Clothing is a major symbol of gender that allows other people to immediately discover the individual’s biological sex. These three Japanese designers challenged the normative gender specificity of Western clothes.’

(Kawamura, 2004: 132-133)

They did not dress the men as men and the women as women; they simply aimed to create garments that covered the wearer regardless of their gender. Many critics saw their designs as tasteless. Some said of Kawakubo’s designs that the women looked like crows (this would be due to the voluminous swathes of black fabric that covered the body). Others saw it as the dawn of a new aesthetic, a new way of looking at fashion and the way we gender our clothing.

Despite their reluctance to be labelled as ‘Japanese designers,’ which made them feel pigeonholed into a group rather than recognised as individual designers, their designs have taken influence from Japan. Inspiration can be said to come from what surrounds you, so it stands to reason that their upbringing in Japan had an impact upon their designs. For example, the influence of the boxy shape of the kimono that, to a western perception, does not adhere to a strict masculine or feminine silhouette, can be seen to an extent in their designs. The kimono, like their designs, is a garment created independent of the wearer – only once someone puts it on does it take any form. The fact that, again to a western perspective, male and female kimono are not overly dissimilar in style and shape can create a more gender neutral starting point.

Japan was not the only place they drew inspiration from, though, and this can be quite obvious in Kawakubo’s choice of brand name, Comme Des Garcon (Like the Boys), a nod to the much revered Coco Chanel. Chanel was certainly a starting point for the movement towards genderless clothing. She took inspiration from working men’s clothing and adapted it for women, doing away with the tight, restricting corsets and skirts of the time. This trend made its way over to Japan in the mid 1920’s, when the Japanese moga, or ‘modern girl’, began dressing in a westernized fashion, eschewing the kimono and opting for slack trouser pants and loose clothing. This was a far cry from the traditional Japanese view of feminine, and they were often tormented in public and called ‘garcon’ by newspapers at the time. This, too, seems to have impressed itself upon the way the designers created their own collections. But where Chanel still tailored mainly for women, Kawakubo, Miyake, Yamamoto, and Kansai created garments meant for either sex to wear. Though Chanel was one of the pioneers of genderplay in fashion, these designers combined their own cultural understandings of fashion with modern techniques to create something entirely new. It was a blend of both Japanese and Western aesthetic, both married and deconstructed at the same time, that allowed the designers to make a name for themselves that still holds power today.

This has allowed many to express themselves in new ways, personal ways.

Kawakubo, Miyake, Yamamoto, and Kansai, among many others, have sparked many subcultures of fashion, not just here in Japan, but globally. From this we have seen a rise in clothing designed for any and all people, regardless of gender. This has allowed many to express themselves in new ways, personal ways. Here in Japan, their vision lives on in the fashion subcultures, like genderless kei, that we see today. In doing so, Japan keeps the rest of the world on its toes, watching to see what will come next.

(Harvard referenced)

KAWAMURA, Y (2004) The Japanese Revolution in Paris Fashion, Oxford/New York: BERG