Jessica Craven (Saitama)

Some of Japan’s oldest surviving textiles, dating from the 8th century in the Nara period, are contained at Tokyo National Museum’s Gallery of Horyuji Treasures. The collection primarily contains ban, or Buddhist ritual banners, from this era. Even though these early designs are rather simple, if you look closely you can discern the intricate attention to detail and craftsmanship that is characteristic of other Japanese products, such as its renowned stationary. While the designs consist of only one color, very delicate and complex textural patterns have been skillfully woven into the fabric.

Some of Japan’s oldest surviving textiles, dating from the 8th century in the Nara period, are contained at Tokyo National Museum’s Gallery of Horyuji Treasures. The collection primarily contains ban, or Buddhist ritual banners, from this era. Even though these early designs are rather simple, if you look closely you can discern the intricate attention to detail and craftsmanship that is characteristic of other Japanese products, such as its renowned stationary. While the designs consist of only one color, very delicate and complex textural patterns have been skillfully woven into the fabric.

Until now, I had admittedly never really thought much about Japanese textiles. Like most foreigners (and perhaps even some Japanese people), I only ever really thought of kimono when I thought of traditional Japanese textiles. And while many pieces of kimono-inspired contemporary clothing are made today, they are scarcely designed with the same level of craftsmanship and elegance that the traditional kimono are. For the most part, even clothing inspired by traditional Japanese fashion is today made in a factory. This led me to wonder… aside from kimono, are there any traditional textile techniques that are being preserved in Japan today, and are they being modernized to suit contemporary taste and practical wear?

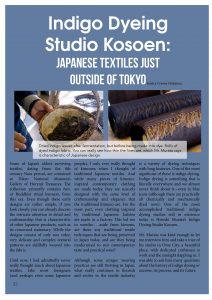

Although some unique weaving practices are still thriving in Japan, what really continues to flourish and evolve in the textile industry is a variety of dyeing techniques with long histories. One of the most significant of these is indigo dyeing. Indigo dyeing is literally everywhere — even in blue jeans (although these are practically all chemically and mechanically dyed now) — and yet we practically never think about it. One of the most accomplished traditional indigo dyeing studios still in existence today is Hiroshi Murata’s Indigo Dyeing Studio, Kosoen.

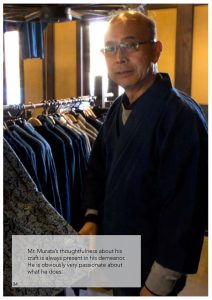

Mr. Murata was kind enough to let me interview him and take a tour of his studio in Ome City, a beautiful place with dedicated craftsmen at work and the sunlight dappling in. I was able to ask him many questions about the history of indigo dyeing, or aozome, its process, and its future.

Jessica Craven: What is Ome City’s history with aozome?

Hiroshi Murata: Textile production has prospered in this area since the 13th century, including the introduction of traditional indigo dyeing during the Edo period (when the process first began in Japan). Demand for textiles, such as bedding, skyrocketed in the post-war period, and Ome City provided close to 50% of the national demand. This studio, which was established in 1919, greatly contributed to that. I inherited the family business in its third generation, and still continue the tradition of indigo dyeing today. Since inexpensive textile imports have increased dramatically, hundreds of companies have abandoned this practice, so Kosoen is one of the only studios of its kind today, and the only one left in Ome that still uses a completely traditional process. Kosoen uses indigo leaves that are grown and fermented traditionally in Kochi prefecture.

prospered in this area since the 13th century, including the introduction of traditional indigo dyeing during the Edo period (when the process first began in Japan). Demand for textiles, such as bedding, skyrocketed in the post-war period, and Ome City provided close to 50% of the national demand. This studio, which was established in 1919, greatly contributed to that. I inherited the family business in its third generation, and still continue the tradition of indigo dyeing today. Since inexpensive textile imports have increased dramatically, hundreds of companies have abandoned this practice, so Kosoen is one of the only studios of its kind today, and the only one left in Ome that still uses a completely traditional process. Kosoen uses indigo leaves that are grown and fermented traditionally in Kochi prefecture.

JC: So indigo dyeing began in India and spread to many other countries, right? What sets Japanese indigo dyeing apart?

HM: My studio utilizes more thin lines and delicate patterns. Also, the exact fermentation process has evolved differently in Japan, and this results in a unique shade of blue. It involves two different and separate fermentation processes. The first is the process of making indigo leaves into sukumo, which is the raw material that is made into dye. The second fermentation transforms sukumo into indigo dye. Then the actual fabrics are dyed using many techniques similar to the ones in ukiyo-e. The process from start to finish takes several years, but the dyeing itself takes much less time, although careful attention to detail is required.

HM: My studio utilizes more thin lines and delicate patterns. Also, the exact fermentation process has evolved differently in Japan, and this results in a unique shade of blue. It involves two different and separate fermentation processes. The first is the process of making indigo leaves into sukumo, which is the raw material that is made into dye. The second fermentation transforms sukumo into indigo dye. Then the actual fabrics are dyed using many techniques similar to the ones in ukiyo-e. The process from start to finish takes several years, but the dyeing itself takes much less time, although careful attention to detail is required.

JC: What inspired you to continue the indigo dyeing tradition?

HM: As I said, I inherited my family business, but actually I changed it dramatically in 1989. I was convinced that only a return to the quality of Edo-period indigo dyeing would allow our business to continue to prosper under fierce competition from cheap imports. So, we went to Tokushima prefecture to learn traditional indigo dyeing techniques. I wanted to revive these refined techniques and make them known to the rest of the world.

JC: What are you doing to modernize indigo dyeing and make it appealing to people today?

HM: One appeal is our use of only natural techniques. Our products are completely devoid of harmful chemicals, so they are good for the environment and the people who wear them. There has also been renewed interest in the revival of traditional craftsmanship in Japan. When we first revitalized our business in 1989, our sales were small, so we only made small things like table centers, coasters, and other interior household items. However, about ten years ago we gained more popularity have begun dyeing and designing clothing, so that gives us ample opportunity to both continue traditional designs and modernize them by dyeing more contemporary style clothing.

our use of only natural techniques. Our products are completely devoid of harmful chemicals, so they are good for the environment and the people who wear them. There has also been renewed interest in the revival of traditional craftsmanship in Japan. When we first revitalized our business in 1989, our sales were small, so we only made small things like table centers, coasters, and other interior household items. However, about ten years ago we gained more popularity have begun dyeing and designing clothing, so that gives us ample opportunity to both continue traditional designs and modernize them by dyeing more contemporary style clothing.

Mr. Murata’s indigo Dyeing Studio Kosoen has certainly gained commercial success, receiving a significant number of overseas orders and more foreign visitors than ever before. He has even received invitations to exhibit in Germany and Canada, as well as to sell products at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In spite of this, his studio was featured in “The Wonder 500,” a list of certified products selected to be “local products that are the pride and joy of Japan but not yet known outside of Japan.” Let’s change that! Mr. Murata’s passion for his craft allows him to create astonishingly beautiful works of art, so please check them out online, if only to gain a deeper appreciate for the art of indigo dyeing!

Jessica Craven is an ALT in Saitama prefecture. She has degrees in both visual art and Japanese, so she enjoys exploring the contemporary art scene in Japan.

![CONNECT ART ISSUE 2024 SUBMISSIONS [CLOSED]](http://connect.ajet.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ARTISSUE-INSTA-600x500.png)