A review of Beyond Kawaii: Studying Japanese Femininities at Cambridge

This article originally featured in the March 2021 issue of Connect.

Alice French (Yamagata)

What was the last thing you referred to as ‘kawaii’? As of writing this, the last time I used the word ‘kawaii’ was when cooing at a sausage dog wearing a tiny coat, whom I encountered in the street over the weekend. I can neither confirm nor deny whether said sausage dog considered the comment a compliment, but I’m almost certain that he/she was not aware of the gendered and societal nuance underpinning this seemingly innocent adjective.

The now increasingly globalised Japanese word kawaii literally translates as ‘lovable,’ comprised of the Chinese characters 可 (ka, meaning possibility/ability) and 愛 (ai, meaning love/affection). Over the last few decades, the term has come to encompass all things cute in Japanese popular culture, from anime characters and pop idols, to wedding dresses and lingerie. Kawaii is also the default adjective for describing babies, children, pets, and even grandparents. In fact, pretty much anything and anyone can be kawaii if you look hard enough.

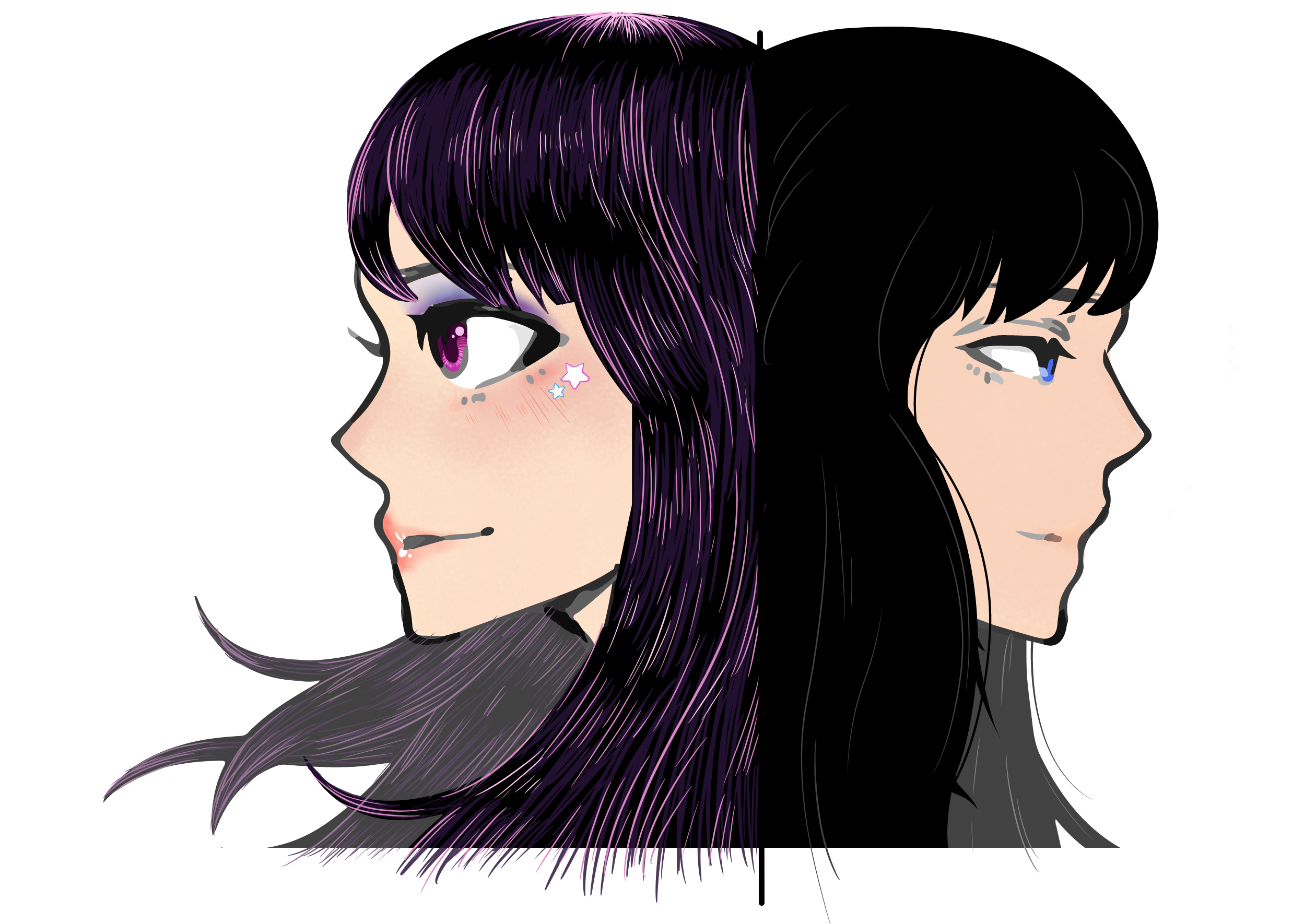

However, as revealed in the latest book from Cambridge University’s Japanese Studies Department, the sociological impact of kawaii in Japan stretches far beyond its humble adjectival beginnings. Look hard enough at the plethora of kawaii characters, costumes and products available in Japan, and you will notice an undeniable common theme. All are innately, and painfully stereotypically, feminine. This femininity most ostentatiously manifests in the form of the pink, fluffy, and frilly kawaii-ness that we all know and love, and more stealthily as the obedient, quiet, and infantile kawaii-ness that often goes hand-in-hand with these girly aesthetics. A good example is Japan’s famous Hello Kitty character, who is characterised by her disproportionately large eyes, pink or red bow, and lack of mouth (and thus her inability to speak). Although the beloved kitty-chan is perhaps an extreme case, this same kawaii-fied femininity can also been seen in any doe-eyed, school uniform-wearing, shrill-voiced female anime or manga character, such as family favourite Sailor Moon.

Beyond Kawaii: Studying Japanese Femininities at Cambridge, edited by Brigitte Steger, Angelika Koch and Christopher Tso, explores this link between the kawaii phenomenon and femininity in modern Japan, through the lens of female sexuality, motherhood, body image, fashion, film and literature. As explained in the book’s introduction, kawaii ko (cute girl) has come to be one of the many ideals that women in Japanese society are expected to aspire to, along with devoted mother, obedient wife and, more recently, career woman. The kawaii ideal holds a special kind of gravitas because of its prominence as “one of Japan’s most successful global exports,” which has “replaced the kimono-clad geisha figure as the dominant image of Japanese women” not just domestically, but all over the world. (12) Although the pink, fluffy kawaii aesthetic may have held some potential for subverting the “orthodox values of social responsibility” expected of women by Japanese society when it first emerged in the 1970s, as it has become more mainstream, the social pressure to be seen as kawaii, not only by men, but also by fellow women, has proved it to be more restrictive than progressive. (13)

Any fellow women (or, indeed, fellow humans) with any experience of living in Japan will no doubt have felt the restrictive force of the kawaii phenomenon first-hand. Youtube adverts from sparkly cosmetic brands promising to up your kawairashisa (kawaii-ness) and bag you a boyfriend; well-meaning comments from your co-workers about how kawaii you look, on the one day that you wear your hair down and remove your glasses; accusatory glances from obaa-chan on the subway if you sit with your legs open; the list goes on. If you are one of the braver among us who has dipped your toe into the Japanese online (or even, *gasp,* real-life) dating scene, you will most likely have been subjected to unsolicited comments such as ‘you’d be so kawaii if you just lost a bit of weight,’ or ‘you’re kirei (pretty) right now, but you were so much more kawaii in that picture of you with longer hair from 2 years ago.’ The power of kawaii even extends into the workplace; note how female colleagues often raise the pitch of their voices at least a couple of tones when taking phone calls (whereas male colleagues’ voices remain unchanged), and cover their mouths or stare at the floor when laughing/giggling in the office. After nearly two years of working in a Japanese office, I’ve found myself picking up some of these kawaii-fied habits almost automatically.

As the title suggests, Beyond Kawaii delves into some of the ways that Japanese women are attempting to, or being expected to, expand their feminine identity outside of the confines of the kawaii ideal in modern society. Against the backdrop of Japan’s aging society and Abe Shinzō’s disappoint-ing ‘womenomics’ policy, the book provides a unique and refreshing perspective on Japanese femininity that extends beyond the solely maternal and economic roles that have dominated English language research into Japanese women thus far.

Chapter One’s investigation into the recent shikyūkei (uterus-type) and chitsukei (vagina-type) spirituality trend is especially interesting, as it sheds light on a hitherto largely unknown and unresearched aspect of the Japanese women’s movement. In this chapter, Ellen Mann looks at the presentation of this new form of spirituality, which encourages women to harness their feminine energy and happiness through forming a deeper connection with their reproductive organs, in women’s magazines and online platforms. This movement, which is one result of the growing interest in ‘spirituality’ in Japan since the 1980s, calls for women to practice special vagina-strengthening exercises, masturbate, and even examine their menstrual blood, all in the name of getting more in touch with their ‘feminine’ selves.

I found Mann’s research especially fas-cinating when compared to the current move towards sexual liberation and sex positivity for women (and all non cis-het males) that is so prevalent on Western social media (particularly Instagram) at the moment. Whereas the Western movement is more about women reclaiming their bodies and sexuality as a form of liberation from the restraints of traditional expectations of femininity, Mann finds that shikyūkei and chitsukei approaches to female self-improvement ultimately “replicate rather than resolve the pressures facing contemporary Japanese women.” (74) This is because, in Japan, the practice is not a form of personal liberation but a method of self-improvement, aimed at making women more attractive and useful to society. The movement can therefore be seen as an addition, rather than an alternative, to the other burdens placed on modern women (such as having to juggle childcare with maintaining a career). I highly recommend Mann’s research to readers of any gender, not least because it is brilliant fodder to spice up the small talk during your next coffee break at work.

I found Mann’s research especially fas-cinating when compared to the current move towards sexual liberation and sex positivity for women (and all non cis-het males) that is so prevalent on Western social media (particularly Instagram) at the moment. Whereas the Western movement is more about women reclaiming their bodies and sexuality as a form of liberation from the restraints of traditional expectations of femininity, Mann finds that shikyūkei and chitsukei approaches to female self-improvement ultimately “replicate rather than resolve the pressures facing contemporary Japanese women.” (74) This is because, in Japan, the practice is not a form of personal liberation but a method of self-improvement, aimed at making women more attractive and useful to society. The movement can therefore be seen as an addition, rather than an alternative, to the other burdens placed on modern women (such as having to juggle childcare with maintaining a career). I highly recommend Mann’s research to readers of any gender, not least because it is brilliant fodder to spice up the small talk during your next coffee break at work.

As someone who has struggled with heightened body consciousness pretty much daily since moving to Japan, I also found Chapter Five, in which Anna Ellis-Rees discusses the dynamic between Japan’s kawaii phenomenon and its body positivity movement, very engaging. Focusing on the trend of ‘chubby’ (puniko) girl idol groups and the messages of supposed body positivity and fat positivity that they promote, Ellis-Rees investigates whether the “soft, round and squishy” version of the kawaii ideal that has emerged over the last decade offers any respite from the traditional pressure on Japanese girls to be small, slim and lady-like. As you can probably guess, her conclusion is that it does not, but this chapter provides a meticulously-researched insight into Japan’s diet culture and its attitude towards the ideal female body, which I’m sure many readers will relate to.

The above two chapters are just my personal highlights, but all essays in Beyond Kawaii are well worth reading. Tianyi Vespera Xie talks about the pressures of modern motherhood as well as the potential for the ikemen dansō cosplay trend to subvert gender norms. Alexander Russell introduces us to award-winning author Kanehara Hitomi’s novel ‘Trip Trap’ and the ways in which it deals with the multi-faceted and, quite frankly, exhausting challenges of being a modern Japanese woman. Ellis-Rees also has another brilliantly-written chapter on the destructive power of a woman scorned, as expressed in J-Horror films of the 1990s and 2000s. Whichever aspect of Japanese culture you are interested in, there will be a chapter for you. What’s more, it’s International Women’s Day this month, so what better time to expand your knowledge of Japanese femininity beyond the inescapable kawaii ideal?

Beyond Kawaii: Studying Japanese Femininities at Cambridge is available on Amazon here.

Alice French is a second-year CIR from Cambridge, England, based at the Pre-fectural Office in Yamagata. When she is not singing in the shower or taking pictures of sunsets for Instagram, she can be found hiking or skiing on one of Yamagata’s many mountains.

![CONNECT ART ISSUE 2024 SUBMISSIONS [CLOSED]](https://connect.ajet.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ARTISSUE-INSTA-600x500.png)