This article originally appeared in the December 2022 issue of CONNECT.

Kasia Majewski (Aichi Prefecture)

An Island of Marvels

Yakushima Island is a mountain range that juts out of the sea, sharply rising to nearly 2,000 meters above sea level. It was one of the first recognized UNESCO Natural Heritage Sites and Biosphere reserves in Japan, boasting over 1,900 species of plants and 2,000 species of animals, many of which are found exclusively on the island.

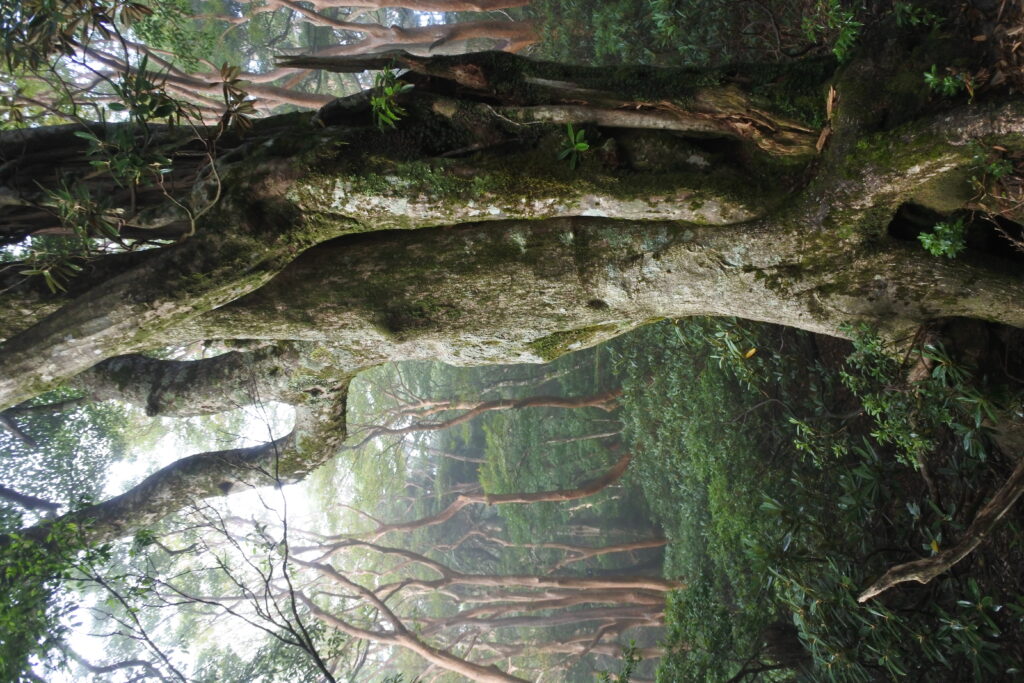

Towering above them all are the Yakusugi Cedar trees, many of them centuries or even millennia old. These ancient behemoths were once logged, and the remnants of a logging railway still snakes its way through some of the oldest woodland on the island. Thankfully, after its designation as a National Park and UNESCO Natural Heritage Site, the logging ceased, and the railway now serves as part of a unique heritage trail to visit the oldest-known remaining tree on Yakushima, Jomonsugi, which is thought to be between 2,000-7,000 years old.

Moving beyond the moss-clad forests, you quickly end up high in the mountains among the island’s unique alpine species. If you catch the weather at the right moment on the highest peak, Miyanouradake (1,936 meters), you can gaze down the length of the island in each direction to the sparkling blue of the sea.

To the northwest, you can even catch a bird’s-eye view of Nagatahama—-a site of immense importance as it is the largest remaining nesting site for endangered loggerhead sea turtles in the Northern Hemisphere. An estimated 40% of the world’s remaining loggerhead sea turtles come to nest on this beach. Endangered green sea turtles also nest here. The waters beyond the island are protected as they carry an immense wealth of aquatic species, from flying fish to bioluminescent firefly squid that light up the sea with flickering green light during the summer months.

It’s easy to see why Yakushima is such a popular destination for local and international tourists alike. As an avid hiker, I couldn’t wait to get my boots on the ground to see as much of the island as possible, and not just out of love for wild spaces. The precedent for my off-grid wild adventure across the heart of the Yakushima begins with the introduction of a potentially devastating invasive species nearly 50 years ago.

Tracking an Unwelcome Invader

Raccoon dogs, or tanuki, were introduced to Yakushima from mainland Japan in the 1970s, and recent anecdotal reports suggest that the population of this invasive species has grown very large. We know from ecological research in Europe, where tanuki are also invasive, that their populations can spread rapidly and wreak havoc through competition with native species. Their impact on the diversity on Yakushima has been largely unstudied until now.

Arriving at the island at the start of August, I was continuing my research on the impacts of invasive tanuki, particularly focusing on their impact on endangered and endemic species on the island. My research is focused predominantly on the Seiburindo Coastal Forest, but I’ve been wondering just how widespread their population is on Yakushima and how far they’re reaching into the mountains.

At the end of my six-week field research period, I packed my tent, sturdy hiking boots, water, and instant ramen and decided to find out.

Day One: Summiting Miyanouradake – The Roof of Yakushima

I decided to take the most popular route, beginning at Yodogawa Trail Entrance. Conveniently, there is a public transport bus that deposits hikers two to three times a day at this entrance. My plan was to hike across the two of the highest peaks on the first day, then spend two days descending through the old-growth forest, with a stop to see Jomonsugi. Along the way, I was on a mission to find traces of tanuki—especially tanuki scat—-to confirm their presence in the mountains.

While the main trail network on Yakushima is in excellent condition, hikers must take extra care with planning for the weather, avoiding periods of heavy rain or strong winds. There is no electricity or running water along the trail. Many of the hikers drink directly from the water springs located along the way, but as a biologist working in a parasitology lab, I would strongly advise against this approach. I brought a small water filtration system with me and boiled my water before drinking it.

The view from Miyanouradake is breathtaking. The trails at this elevation are carved into the thick bamboo grass that blankets the mountains, with rock faces reaching up out of the sea of green.

I reached the summit of Nagatadake about an hour after leaving Miyanouradake, and this is where the hike became a bit more challenging.

Planning to reach Shikanosawa hut (1,550 meters) for a place to overnight, I descended down a much more worn trail full of teetering ladders and washed out sections. Luckily, pink markers on branches still led me safely to my first mountain hut. This stone hut is very basic, and the area around it was submerged under a centimetre of water, so I decided to forego my tent and sleep under the cover of the stone hut’s roof. Camping in the Yakushima mountains is only permitted adjacent to the mountain huts. Keep in mind the popularity of the trails during Obon and Golden week when planning your stay in the mountain huts.

Day Two: Second Summit of Nagatadake and Yakusugi Forest

After my first night in Shikanosawa Hut, I began my second day by summiting Nagatadake yet again to continue on to Shin-takatsuka mountain hut (1,460 meters), which is approximately one hour away from Jomonsugi.

I was less fortunate with the weather this second day with some light rain falling most of the morning. I was grateful for the rope lines installed across the bare rocks as even with a little precipitation and sturdy hiking boots, these become very slippery rapidly.

For parts of the day, I kept the company of Yakushima macaques along the trail. These are a subspecies of Japanese macaque found only in Yakushima, and like the sika deer that also roam the island, they are considerably smaller than their mainland counterparts. Nonetheless, they are wild animals, and I exercised caution while moving past their foraging groups.

I was also thrilled to meet a Yakushima weasel—a species I believe is in direct competition with invasive tanuki as the only native small carnivore on the island—right on the trail.

Shikanosawa Hut looks like it was plucked directly from a Studio Ghibli film. It is a wooden structure covered in moss and surrounded by gnarled yakusugi cedar, and a small family of sika deer silently departed the front veranda as I approached. A large wooden platform just outside the main entrance also facilitates a comfortable space to camp. It is the perfect setting to overnight and prepare oneself for arriving at the base of one of the oldest trees in the world the following day.

Day Three: Jomonsugi and the Rail Trail

Each day on the trail felt like the absolute pinnacle of beauty, but just when I thought it couldn’t get any more incredible, it did. The section of trail between the Shin-takatsuka Hut and the Arakawa Trail entrance, which was to be my exit, is all old-growth, mossy forest. My luck with the weather had thoroughly run out, and I was caught in some rainfall, so the descent took extra time on the slippery wooden steps that cover much of the trail toward Jomonsugi and further on to the heritage rail trail.

Arriving at Jomonsugi was probably the closest I will ever be to meeting an ”Ent” from Lord of the Rings. This was the first section of trail that had a number of other hikers on it, as tour groups frequently depart to see this ancient resident of the forest. The sheer magnitude and character of this tree awed us all into silence as we stood on the mossy viewing platform, looking up into the mist gathering around its crown. Seeing this remaining ancient of our world gave me a particular sense of purpose and pride in the work I was undertaking to contribute to the conservation of this island.

The final portion of the old logging trail snakes through the mountains and, in mid-September, already feels autumnal, with large amanita mushrooms sprouting out from the moss between yellow and red fallen leaves.

The gradient here is very gentle, and signposts along the way provide information in multiple languages about the natural significance of the forest and the impacts of the logging industry. As an ecologist, I am always thrilled to see outdoor enthusiasts having opportunities to learn about protecting wild spaces.

As with the Yodogawa entrance, the Arakawa entrance has multiple buses servicing it per day, so departing the mountains to return to my field station was fairly convenient. I didn’t find traces of tanuki scat this time, but to my surprise, I found numerous Yakushima weasel scats along the trail. These could provide invaluable information on this little-studied subspecies’ diet and the comparison of its diet to the invasive tanuki for a better understanding of how vigorously the two species compete with one another. More importantly, this hike promotes such a strong feeling of connection to our natural world, I felt reinvigorated after six weeks of difficult field work to keep on with my research and continue to be a part of the network of hardworking researchers and volunteers who are instrumental in protecting this island for future generations of local people and visitors alike.

Kasia Majewski fell in love with the wilderness in Japan as a JET in Shimane Prefecture between 2015-2016 and remained on the lookout for opportunities to return to Japan ever since. In 2021, she was granted an incredible opportunity to return to Japan as a Monbukagaksho (MEXT) scholarship recipient, which offers a fully-funded opportunity for post-secondary students to study in Japan in a subject of their choice. She is now a Kyoto University graduate student, and her research site is Yakushima. You can find more details about her research here.