This article is part of a web original series

Marco Cian (Hyogo)

The popular image of a creator is that of Howard Roark, a lone genius who strives against those who would stifle or misinterpret his creative vision, such as fatuous editors who demand cuts or snobbish critics who only say mean things out of envy. And if there are other people involved in the production of Roark’s work, they are merely puppets carrying out his vision, their own talent judged by how much they dilute or distill the creator’s genius.

This is, of course, nonsense. Even in something like prose fiction, perhaps the least collaborative creative medium, there are still publishers, proof-readers, and other people who help the writer come up with the final story we see on the page. And as for something like filmmaking, there are so many different moving parts in the process that it’s impossible to credit the final product to any single person, even if the screenwriter or director help steer the ship in a cohesive direction.

This is also to say nothing of how stories and art survive, not by being told, but by being retold and reworked with each passing generation. This is why the griots scoff at the idea of books, and why even the biggest King Arthur fan won’t defend the notion that the Icelanders are a slave race fit only to lick their English masters’ boots (even though that’s very much a part of early Arthurian stories). Even within the same generation, adaptations from one medium to another often involve different creators with different perspectives on the subject matter. That’s why Jack Torrence goes from a sympathetic character to a more villainous one in the film adaptation of The Shining. That’s why people fondly remember M.A.S.H. as a heartfelt tv drama and not a wildly sexist book. And that’s why I’m interested in checking out the manga version of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Some context. Anime is very costly to make, because of all the aforementioned moving parts. So most anime consists of adaptations or tie-in media, so that the program will already have a stable fanbase they can count on upon release. Today, an anime being a completely original work is rare, but in the 90s, it was unthinkable, which is why, when Anno first pitched the idea that would become Neon Genesis Evangelion, a tie-in manga series was conceived concurrently to drum up interest in the project.

This manga is interesting for several reasons. Firstly, it’s the first piece of Evangelion media without Anno’s involvement, made entirely by the show’s lead character designer Yoshiyuki Sadamoto. Secondly, Sadamoto’s motivation for finishing the manga (after copious delays) was simply a feeling of obligation to fan demand, as opposed to Anno’s motivation of artistic integrity. And thirdly, because of these copious delays, Sadamoto was informed by all three versions of Anno’s Evangelion: the original NGE show, the End of Evangelion movie, and the Rebuild of Evangelion films, incorporating bits and pieces from all of them into the finished product.

I mentioned in my review of EoE that the main obstacle to it being a satisfying conclusion to the Evangelion saga was most likely Anno himself. With his own mental state preventing him from keeping an objective distance from the work, the finished product is less a proper ending to the series and more an unvarnished reflection of Anno’s own deteriorating psyche. Perhaps, like Kubrick with King, Sadamoto has the distance necessary to deliver a satisfying story removed from personal baggage. Or, perhaps this distance will result in disaster. There’s only one way to find out.

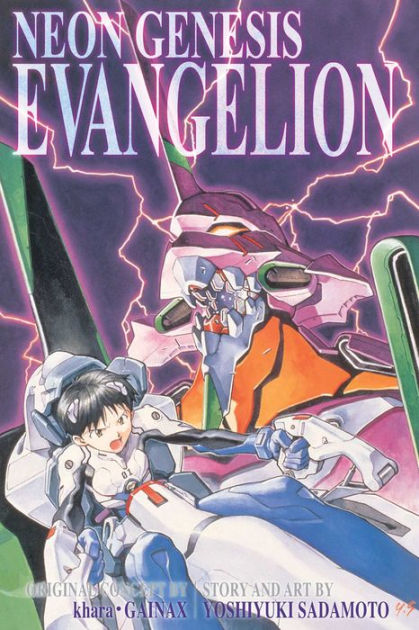

Neon Genesis Evangelion

The NGE manga is fascinating to read, not just because of the story itself, but in how the story is presented to readers. The first chapters came out back when English translations of manga were still printed like American comic books, each chapter getting its own issue with flipped imagery, cover art, and a letters section where you could read fan mail and see fan art submitted by readers. It’s so fascinating reading the manga in this way, because it means you not only get to read the story with scripts as well-translated as the ADV dub, but you also get a snapshot into what the anime fandom was like in that time and place. Seeing Talmudic scholars try to decipher the show’s symbolism, reading the comic editor somberly discuss the then-recent tragedy of Columbine, checking out the art eager fans made of their favorite characters, it left me feeling nostalgic for a time when I was only a wain. I know it will never happen, but there’s a part of me that wishes they would bring back this way of printing manga for English-speaking audiences, or at least print the whole NGE manga series this way.

As for the story itself, while the manga faithfully adapts the basic plot beats of the anime, things are always just slightly different. Whether it’s a more overt horror tone, certain characters behaving differently than we expect, or some scenes being excised or combined, the overall result is a story that is almost, but not quite, entirely unlike Neon Genesis Evangelion.

In some cases, this is spectacular. Shinji for instance is only slightly different from his anime counterpart, but these slight differences create a wildly altered character. Shinji in the anime is someone who chooses to cloister himself from the world when confronted with hatred or conflict. But Shinji in the manga believes that the best way to deal with people hating him is to calmly accept it. If it’s inevitable that no-one will ever show him love or kindness, then there’s no point in getting upset over it, right? He just has to soldier on, and eventually, he’ll be okay with the situation. That’s what Shinji tells himself, and as we get far more insight into his upbringing than we did in the anime, we can see just how hellish his life before NERV was, and why this acceptance is the coping mechanism he settled on. But even as Shinji says he’s okay, you can see from his actions and his moments alone that he isn’t really, he just needs to believe that he is so that he can carry on.

Shinji in the anime knows that he isn’t okay, but needs to learn how to confront his issues head-on instead of running away from them. Shinji in the manga needs to realize that he isn’t okay, and that it’s alright for him to want more in life, to want human connection and happiness. For both Shinjis, the answer to their woes comes from self-love and self-acceptance, but for Shinji in the manga, he’s far more assertive and confident, allowing him to take steps in his healing on his own once he understands what the issue is, and to not let people treat him poorly even in the beginning.

I confess, if I’d had this manga to read back in High School, my little AsuShin shipper heart would have exploded from cholesterol from all this fresh red meat they give us! And Shinji’s relationship, not just with Asuka, but with everyone else, is far healthier in the manga because of his assertiveness. Instead of allowing people to walk all over him, Shinji will call people out on their bullshit, and even take direct action when he sees something he can’t abide. And this makes his relationship with Asuka take on a new and wonderful form when she finally appears in the manga.

There’s a certain relationship dynamic you see a lot in anime. Just off the top of my head I can think of it in Oreimo, Haruhi Suzumiya, and Ocean Waves. But it’s where a pushover everyman warms the icy heart of a demanding diva through general decency. We’re supposed to cheer for these relationships because at last, someone got through her cold exterior, someone like… you, perhaps? And this gives us schlubby everymen hope that we too can acquire the heart of the Queen Bee diva of our school.

Of course, this is a rather warped view of love and relationships, especially when said diva only changes her attitude towards the pushover protagonist, and not anyone else, because it’s basically saying “I’m fine if the hot girl I like is a bitch, just so long as she isn’t a bitch to me.” But what I love about Shinji and Asuka in the manga is that the story recognizes and addresses this. Yes, Asuka may be popular and beautiful and a genius, but she still has her own issues that she needs to work through, and she doesn’t have the right to treat people terribly just because she has her own trauma to deal with. The foundation of her relationship with Shinji is in learning to open up and rely on each other, as they mutually work on their own, respective issues. They become each other’s support, but they don’t become each other’s crutches, and the manga is clear that they’ll both need to grow before a healthy romance can really bloom between them.

However, this leads to the basic issue with the manga’s adaptational policy. Sadamoto will create subtle differences and craft new scenes that lead to butterfly effects in the story, and these scenes are really beautiful! Shinji and Rei by the pool, Shinji and Asuka growing fond of each other during training, the way Misato and Kaji’s relationship plays out, these are all such wonderful moments that deserve to be explored further. But whenever these moments happen, Sadamoto will remember that he’s ultimately adapting a story that was already set down, and subsequently the characters will snap back to their anime forms so that the plot can progress as it’s supposed to.

The manga is very good at smoothing out the anime’s rough edges. Every scene from there that made me cringe, groan, or livid (like the scene over the body) is replaced with a much better version of events that would fit right in with the anime. But in smoothing things out, Sadamoto also streamlines and sheds several episodes’ worth of story. The manga really only replicates about half of the anime’s plot material, keeping only the choicest moments and Sadamoto’s own original content. But this can sometimes mean that when our favorite moments from the anime arrive in the manga, the scenes no longer have the same weight they once did, Sadamoto having excised the foundational filler that had built them up originally.

That being said, there’s still a lot to love about this manga, especially when Sadamoto is able to weave his own thematic throughlines into the story. There’s an emphasis on hands in the manga that wasn’t present in the anime, not simply in terms of visual imagery, but also in what hands can represent. When we speak of hands, we can mean our physical appendages, but we can also mean our actions. And there are a plethora of uses one can put their hands to, both physically and metaphorically. Our hands can strike, they can caress, they can reach towards goals, they can heal, and they can connect us. The simplest way to show one’s love, the simplest way to physically connect with someone, is to hold their hand. And such a simple act can mean so much, to those who have been so starved of love.

It’s with Shinji’s hands that he pilots the Eva, and protects those he loves. Sadamoto understands what Anno forgot in EoE, that Shinji is ultimately someone who will stand up to protect the people close to him, no matter how much he’s hurting inside. And yet, Sadamoto manages to twist this piece of Shinji’s character so that he can be just as inconsolable as he was at the start of that film, when that plot beat arrives in the manga. Yes, Shinji pilots to protect people. But after the death of Kaworu, as Shinji looks back on his actions, he realizes that what he is supposed to protect (NERV HQ and humanity) is not the same as what he wants to protect (his friends and friendships), and that while he has succeeded in his duty, the friendships and connections he made have all left him one way or another. So in the end, even if he’s a hero who saved the earth, he wasn’t able to save what actually mattered to him.

So when the soldiers find him like they do in EoE, Shinji isn’t catatonic with self-pity. He’s just tired. Tired of losing everyone he’s ever loved. Tired of fighting and killing. Tired of not knowing if he’s doing the right thing anymore. When he’s surrounded by soldiers sent to kill him, Shinji doesn’t run away, because this feels to him like how things were meant to be. This is how it would always end. Better to just accept it, like Shinji has accepted every tragedy in his life. At least this way he can see his friends again in Heaven.

But this acceptance is really just a rationalized form of despair. And Shinji cannot give into despair. As with every ending of Evangelion, Shinji needs to fight through the pain and the trauma and the hopelessness and keep living. Thanks to the love and support of his friends, Shinji is able to heal and grow as a person, and the ending of the manga combines the best aspects of the NGE show, the EoE movie, and its own storyline to construct what is arguably the happiest ending of all Eva, and what is certainly my favorite ending thus far.

However, this leaves me with two nagging thoughts. The first is a question: Could one enjoy this manga without having ever seen the show or movie? After thinking it over, I’m honestly not sure. This is easily my favorite Eva ending, but a big reason that it was so satisfying was that it learned from the mistakes of previous endings. More than that, the manga is littered with call-backs to the source material (and, surprisingly, the last Rebuild film, which it predates by several years), and while the snapping back of characters I mentioned makes sense if you’ve seen the anime, I imagine it would be even more frustrating if you were trying to take in the manga in isolation.

This leads to the second thought. I went into the manga hoping to find the ending that I couldn’t find with the show and movie, and that’s just what I got. As the conclusion to Shinji’s story, this is about as good as it can get, I think. But the thing that sticks out most to me, the thing that leaves me with new feelings of curiosity and listlessness, is those original Sadamoto scenes. I find myself wishing that he had pursued the butterfly effect more ardently, and he had explored the new possibilities he’d opened up.

That’s why I still feel hungry for more Eva, even if the craving has shifted in nature. I want to find more stories like the ones Sadamoto teased at, where Shinji and everyone else are in new scenarios and new dynamics. I want to see NGE’s story not simply retold, but refashioned and reworked, which is why, even if I found what I was looking for with this manga, this series, my search, and Shinji’s story have yet to conclude.

Oh, and also…

(The manga fans will get it)

Marco Cian is a second-year ALT in Hyogo. You can read more of his stuff (including this series) on his website here.

2 thoughts on “The Forerunner of Evangelion”

Comments are closed.