This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of CONNECT.

Ashley Noelck (Tokushima)

Japan is internationally admired for many aspects of its culture, including sushi, anime, and video games. However, I would contend that there is no cultural artefact more well known and entwined with Japanese society and history than sake. Often (incorrectly) referred to as “Japanese rice wine,” this alcoholic beverage is experiencing an international boom. And as a longtime sake nerd I want to share my passion by giving you a brief look into the world of sake.

Japan is internationally admired for many aspects of its culture, including sushi, anime, and video games. However, I would contend that there is no cultural artefact more well known and entwined with Japanese society and history than sake. Often (incorrectly) referred to as “Japanese rice wine,” this alcoholic beverage is experiencing an international boom. And as a longtime sake nerd I want to share my passion by giving you a brief look into the world of sake.

Let’s quickly get vocabulary out of the way. What many foreigners will call sake or rice wine is actually referred to as nihonshu in Japan. Here the word “sake/酒” just means alcohol. But therein lies evidence of its cultural centrality. Nihonshu is made from specialty rice through a unique double-parallel fermentation process. This fermentation method has been developed over thousands of years in Japan and is different from how beer, liquor, and wine are made. Calling it rice wine is inaccurate to the process, although it does reflect its tabletop popularity as a drink with around 15% alcohol by volume (ABV). Additionally, like wine, nihonshu is used in many religious ceremonies as a central part of Shintoism—although it’s not symbolising anybody’s blood. It’s still nihonshu.

History and Traditions

The earliest evidence we have of humans making alcoholic beverages is from 7000 BCE. In what is now called China, people were making fermented alcohol from millet, grapes, honey, and rice. Zooming into Japan, the first written record of a Japanese rice-based alcohol is from a Chinese source from the third century CE. In 689, a nihonshu brewing division was established in the Japanese imperial court and in the eighth century we get the first written records of Shinto mythologies that mention nihonshu. In essence, the traditions and culture around nihonshu have been a part of Japan since before the Imperial Family was established.

The earliest evidence we have of humans making alcoholic beverages is from 7000 BCE. In what is now called China, people were making fermented alcohol from millet, grapes, honey, and rice. Zooming into Japan, the first written record of a Japanese rice-based alcohol is from a Chinese source from the third century CE. In 689, a nihonshu brewing division was established in the Japanese imperial court and in the eighth century we get the first written records of Shinto mythologies that mention nihonshu. In essence, the traditions and culture around nihonshu have been a part of Japan since before the Imperial Family was established.

The tradition of brewing nihonshu most likely started in Shinto temples. In Shintoism, nihonshu plays a central role in many rituals and traditions. It is often used as an offering to the gods, either by being placed at a shine or poured onto the ground. Ritually, nihonshu must always be served to the gods first. Nihonshu plays a role in numerous ceremonies. One of the more common examples is marriage. In a Shinto wedding ceremony the first ritual is the Shinzen kekkon, which can be translated as the “wedding before the kami.” This is a purification ritual centered on the couple sharing nihonshu sometimes referred to as the san-san-kudo or “three-three-nine” ritual. Three ceremonial cups are presented to the couple and they take three sips from each, creating this three, three, nine pattern. Since the number three cannot be divided by two, it symbolizes unity.

Another important tradition using nihonshu is the custom of drinking o-toso on the first day of the New Year. O-toso is a special kind of spiced nihonshu that is said to have medicinal properties. The ritual drinking of o-toso is said to ward off sickness for the upcoming year. There is also a popular saying that goes “if one person drinks it, their family will not fall ill; if the whole family drinks, no-one in the village will fall ill.” This tradition also uses three ceremonial cups, but contrary to most Japanese traditions, it is the youngest person in the family who drinks first. Some say that in this way health and vitality can be transferred from the younger generations to the elderly. If you want to participate in the New Year’s drinking of o-toso, you can buy tea bags called o-toso-san to steep in 300 ml bottles of nihonshu for eight hours (overnight is fine) to make o-toso. This isn’t even the only nihonshu based New Year’s tradition. Taru-zake is a type of nihonshu aged in cedar casks for a few days that is shared in communities and at shrines specifically during New Year celebrations.

Another important tradition using nihonshu is the custom of drinking o-toso on the first day of the New Year. O-toso is a special kind of spiced nihonshu that is said to have medicinal properties. The ritual drinking of o-toso is said to ward off sickness for the upcoming year. There is also a popular saying that goes “if one person drinks it, their family will not fall ill; if the whole family drinks, no-one in the village will fall ill.” This tradition also uses three ceremonial cups, but contrary to most Japanese traditions, it is the youngest person in the family who drinks first. Some say that in this way health and vitality can be transferred from the younger generations to the elderly. If you want to participate in the New Year’s drinking of o-toso, you can buy tea bags called o-toso-san to steep in 300 ml bottles of nihonshu for eight hours (overnight is fine) to make o-toso. This isn’t even the only nihonshu based New Year’s tradition. Taru-zake is a type of nihonshu aged in cedar casks for a few days that is shared in communities and at shrines specifically during New Year celebrations.

Kagami Biraki is a tradition where one breaks the wooden lid of a massive cask of 72 L sake using a big wooden mallet. This tradition is still popular today and can be seen during many different kinds of celebrations and parties from New Year’s to corporate events. Nihonshu is also popularly drunk during hanami celebrations. Hanami is the extremely popular tradition of gathering in parks with family, friends, or colleagues to have a picnic, enjoy speciality food and drink, and view and celebrate the blossoming of sakura and ume trees.

All of these rituals and celebrations are important parts of Japanese life and culture and they all include nihonshu. There are so many traditions involving nihonshu that it is more uncommon to find a celebration that doesn’t involve the spirit in one form or another.

Nihonshu and Shintoism

The first Japanese source mentioning nihonshu is also the oldest extant work of literature in Japan: the Kojiki. This 712 CE compendium of Japanese mythology and history contains the story of Yamata no Orochi. Legends have it that after his expulsion from heaven, the storm god Susanoo encounters an earthly couple weeping. Each year the couple has been forced to sacrifice one of their daughters to the monstrous, many-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi. When Susanoo meets the two, they are being made to sacrifice their eighth and final young girl. Susanoo comes up with a plan to defeat the monster by brewing some especially strong nihonshu. He brews and sets out one barrel for each of the monster’s heads. Susanoo was able to defeat the monster, and from its tail he pulled the legendary sword, the Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi. This sword is one of three sacred artefacts of Japan’s Imperial Regalia, used in the enthronement ceremony.

This myth is just one of many that references nihonshu. It also clearly illustrates how central this drink is to Japan’s history and cultural identity, predating many other traditions and artefacts.

Brewing

Brewing nihonshu requires double-parallel fermentation; but what is that, you ask? Unlike fruits from which wines are made, rice grains do not have much easily available sugars (such as glucose) that can be converted into ethanol by yeast. First, the rice needs to be processed. After harvesting, the rice is polished (tumbled) to remove the outermost protein coat of the grain. This layer is packed full of minerals and proteins which can muddy or diminish the overall taste. The percentage of the rice grain that is left over determines the type of nihonshu that will be made and the price: The more you polish away, the more rice and time it will take. After at least 70% polish, the rice is steamed and inoculated with a special kind of mould called koji (Aspergillus oryzae). This mould is used in a variety of Japanese foods from soy sauce to beef. The organism takes the complex starches present in rice and breaks them down into sugars. This is the first layer of fermentation. After a couple of days of careful monitoring, you have something called kome-koji.

Brewing nihonshu requires double-parallel fermentation; but what is that, you ask? Unlike fruits from which wines are made, rice grains do not have much easily available sugars (such as glucose) that can be converted into ethanol by yeast. First, the rice needs to be processed. After harvesting, the rice is polished (tumbled) to remove the outermost protein coat of the grain. This layer is packed full of minerals and proteins which can muddy or diminish the overall taste. The percentage of the rice grain that is left over determines the type of nihonshu that will be made and the price: The more you polish away, the more rice and time it will take. After at least 70% polish, the rice is steamed and inoculated with a special kind of mould called koji (Aspergillus oryzae). This mould is used in a variety of Japanese foods from soy sauce to beef. The organism takes the complex starches present in rice and breaks them down into sugars. This is the first layer of fermentation. After a couple of days of careful monitoring, you have something called kome-koji.

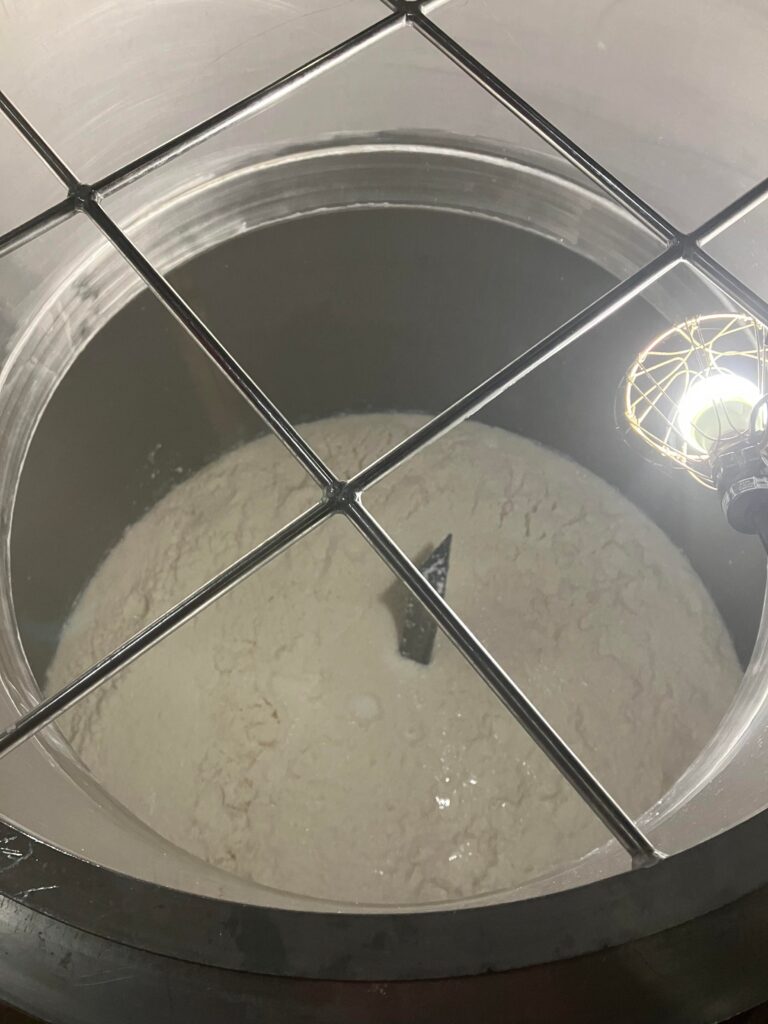

Next, the kome-koji is placed in a vat with water and yeast (or kobo). The particular strain of yeast varies between brewers and can be used as a variable to wildly change the flavour. For instance, there is a nihonshu called Shiraso Shuzo that uses yeast from strawberry flowers. The nihonshu does not contain any fruit whatsoever and yet it tastes like strawberries. Once these three core ingredients of kome-koji, water, and kobo are added, the second fermentation begins. The kobo takes the sugars produced by the koji and turns them into alcohol. Over several weeks, nihonshu master brewers called toji carefully monitor the process, controlling the temperature and pressure while sometimes adding more kome-koji, water, or kobo as needed. Finally, the mixture (called moto) is filtered and pasteurized to varying degrees to create nihonshu.

Classification

There are a lot of different types of nihonshu. It honestly can be a bit overwhelming. But for those who want to get started, there are a few basic types that together make up the majority of nihonshu. Broadly speaking, nihonshu can be split into two families. Those made using only kome-koji, water, and kobo are called junmai. This is considered a purer form of nihonshu and is how nihonshu was made all the way up until WWII. The other family consists of non-junmai types. These have varying levels of special brewer’s alcohol added to them towards the end of production. Small amounts of brewer’s alcohol can be added to highlight more aromatic notes and delicate flavours.

There are a lot of different types of nihonshu. It honestly can be a bit overwhelming. But for those who want to get started, there are a few basic types that together make up the majority of nihonshu. Broadly speaking, nihonshu can be split into two families. Those made using only kome-koji, water, and kobo are called junmai. This is considered a purer form of nihonshu and is how nihonshu was made all the way up until WWII. The other family consists of non-junmai types. These have varying levels of special brewer’s alcohol added to them towards the end of production. Small amounts of brewer’s alcohol can be added to highlight more aromatic notes and delicate flavours.

The vast majority of nihonshu produced today (up to 80%) is a low-grade type called futsuu-shu. These have a larger amount of alcohol added to increase the ABV% and to make it cheaper. The ubiquitous “Gekkeikan Sake” that can be found worldwide (and was the only one commonly available) falls into the category of futsuu-shu. For many people this popular green bottle, white label sake is the first nihonshu they ever try. And if you are one of the folks who tried this and decided you hate sake, please try something better. Any nihonshu you buy in Japan will be better than Gekkeikan Sake.

Moving up in quality from futsuu-shu, nihonshu is typically sorted and classified based on the percentage of rice polish (the percentile number represents the amount of rice left after polishing). A junmai-shu has a 70-61% polish and no alcohol added. A honjozo is the same polish but has a small amount of brewer’s alcohol added to enhance the more complex and even umami notes that can be enjoyed in quality nihonshu.

Ginjo-shu is the word used to describe four different subtypes of nihonshu that all sit at a rice polish of 60% or less. If the word junmai is added at the front, it always means no brewers alcohol added. Junmai ginjo-shu and ginjo-shu are between 60% and 51% rice polish. These kinds tend to be lighter, a little fruitier, and more aromatic. Since more of the outer rice coat has been polished away, it has an overall cleaner taste because there are fewer amino acids and minerals. Junmai daiginjo-shu and daiginjo-shu have 50% rice polish or less. The world record holder for lowest rice polish is a nihonshu made in 2018 by Niizawa Shuzo brewery. This remarkable daiginjo has rice polish of just 0.85%. With such a big category there is obviously a wide range of quality and taste but, overall, daiginjo nihonshu is highly aromatic, clear, and clean tasting.

Ginjo-shu is the word used to describe four different subtypes of nihonshu that all sit at a rice polish of 60% or less. If the word junmai is added at the front, it always means no brewers alcohol added. Junmai ginjo-shu and ginjo-shu are between 60% and 51% rice polish. These kinds tend to be lighter, a little fruitier, and more aromatic. Since more of the outer rice coat has been polished away, it has an overall cleaner taste because there are fewer amino acids and minerals. Junmai daiginjo-shu and daiginjo-shu have 50% rice polish or less. The world record holder for lowest rice polish is a nihonshu made in 2018 by Niizawa Shuzo brewery. This remarkable daiginjo has rice polish of just 0.85%. With such a big category there is obviously a wide range of quality and taste but, overall, daiginjo nihonshu is highly aromatic, clear, and clean tasting.

Other notable categories that can be combined with the aforementioned types include namazake, aged, nigori, and sparkling. Typically, nihonshu is pasteurised twice and best served within one year of bottling. However, samazake is only pasteurised once or not at all and can have a delightful zing to it. If you like whiskey but hate the heartburn that comes with strong spirits, give aged nihonshu a try. Like whiskey, samazake is stored in a variety of barrels or even aged sherry casks and has wonderful, complex flavours with lots of tannins. Nigori nihonshu is often referred to as “unfiltered,” but that’s not really true. It is filtered, just less so than most nihonshu, leaving it cloudy in appearance and much sweeter in taste. Nigori is a massive category to explore and can be very easy and enjoyable drinking for those new to nihonshu. Finally, the latest innovation in nihonshu is the introduction of sparkling varieties, going for that champagne feel. High-end producers strive to make lightly bubbly varieties using natural fermentation without the artificial introduction of gasses, for a very delicate and refined taste experience.

Nihonshu Today

Nihonshu exports reached an all-time high in 2021, with the USA, China, and France all among the top importers. While 15 years ago, one would be hard pressed to find any nihonshu in the local liquor stores in Canada, these days a variety of options are available. As nihonshu’s international popularity increases, brewers have continued to innovate with new techniques. Yet, remarkably, most producers also continue to use traditional tools and knowledge handed down from masters to apprentices. Nihonshu epitomises Japan’s dedication to preserving its cultural heritage while still driving improvement and innovation forward.

Ashley Noelck is a second-year ALT located in Tokushima Prefecture. They are an outdoor enthusiast who loves kayaking and camping. Ash loves learning about culture and history, and is slowly teaching themself bass guitar. Their dream is to go on a cross-country motorcycle tour of Japan.

Image Credits

Julie Brousseau