Reflections on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

This article originally appeared in the November 2022 issue of CONNECT.

Marco Oliveros (Tokushima), Monica Hand (Ehime), Marco Cian (Hyogo), Dianne Yett (Gunma), and Chloe Holm (Ehime)

Many things might come to mind when thinking about what there is to do in Japan, but only two cities in this country—in the world—have the infamous distinction of being sites of nuclear tourism. Present-day Hiroshima and Nagasaki are vibrant, modern, and peaceful cities. However, even if foreign visitors aren’t actively searching for any memorial museums and peace parks, they might walk around certain parts of these cities. They might stumble upon a nuclear monument, exhibit, or ruin . . . and be swept up in thoughts.

As the Culture Section Editor, I’ve asked members of the CONNECT staff to write a few passages about their experiences in Hiroshima or Nagasaki—if there’s something connected to the bombs in those cities that caused them to stop and think. I’ve also added my own reflections. If you make it out to Hiroshima or Nagasaki, we hope these reflections will help you get something more from these trips.

Monica Hand (Ehime)

Hiroshima is a beautiful city. At times, walking around the tranquil and meticulously manicured Peace Memorial Park, it’s possible to forget that, not all that long ago, the city had been utterly devastated. But then, turning the corner, the ravaged Dome appears over the trees, and the horrors that the city and its people had seen become reality again.

That reality hit me hardest on my last morning in the city. I was sitting by the river drinking a vending machine coffee, still groggy with my eyelids hanging heavy. Then it was 8:15 a.m., and the chime rang out. It was the time the atomic bomb struck.

At first, I didn’t register what it was. But as the realization crept over me, so did that nagging pit of dread in my stomach. I knew the stories of where people were when the bomb hit from the museum. The images of school children were still raw in my mind, some still haunt me when I think of it now. But sitting there on that bench it was no longer a face from a black and white photo or painting. It was everyone around me. It was the children passing by on bikes, it was the woman walking her dog, it was my friend next to me on the bench, and it was me.

Monica is a second-year JET living in Shikoku’s Ehime Prefecture. She is also the current Head Editor of CONNECT.

Marco Cian (Hyogo)

Having been to several major historical cities in Japan, I knew before going to Nagasaki that most ancient buildings in this country are regularly rebuilt and refurbished. And several places in Nagasaki follow this pattern. The Dejima I saw was not the Dejima that existed in the Edo period, but a carefully reconstructed replica. And the Chinatown in Nagasaki (Japan’s largest) was destroyed, rebuilt, and expanded with each passing generation.

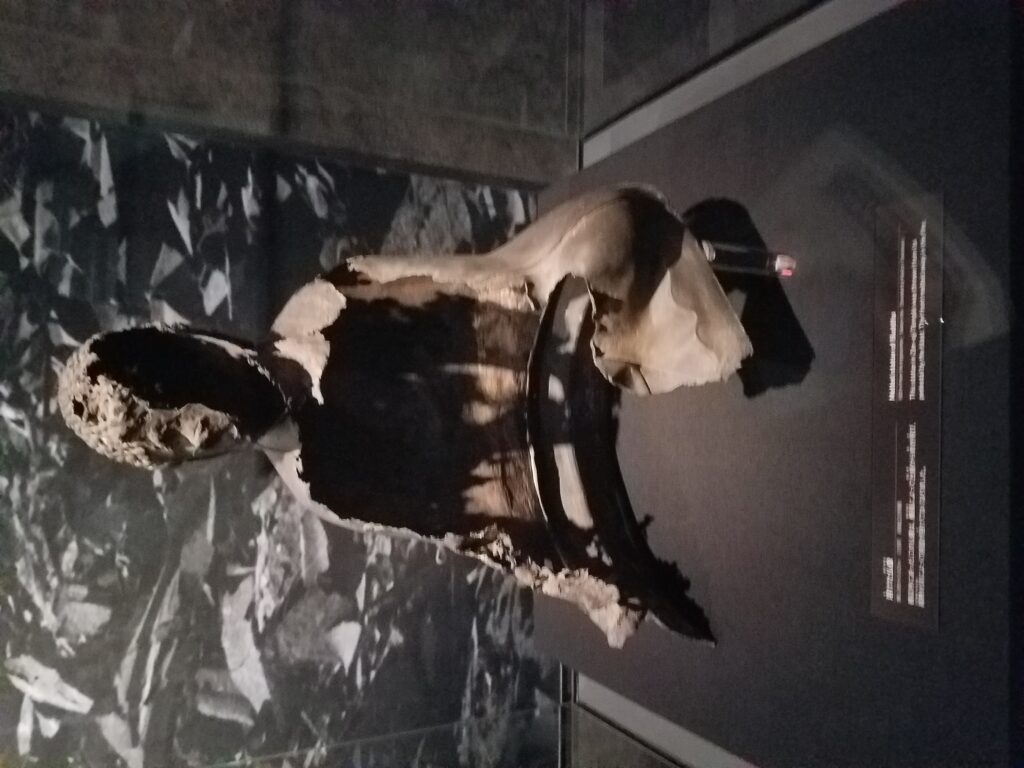

However, architecture in Nagasaki that had survived the bomb was left untouched, as though the places held a certain holiness, or hauntedness, depending on your point of view. The former British Consulate? Left as it was since 1945. The Urakami “Bombed Mary” statue? Preserved as a symbol of rebuilding and survival. I even saw what appeared to be a decaying parking garage in the heart of Nagasaki’s vibrant, neon downtown, overtaken by moss and corrosion. In any other city, such a sight would be demolished, but that garage had survived the bomb, so it was not to be touched.

I went to Nagasaki in 2015, when the Japanese government was reinterpreting the role of its military. There were protesters throughout the city, pleading the government to not go through with its plans for re-armament, to not forget what war brings. With such architecture around them, I could see why it remains difficult for the people there to forget.

Marco Cian is a second-year ALT in Toyooka, Hyogo and a Website Editor for CONNECT. You can read more of his stuff on his Substack.

Dianne Yett (Gunma)

There are a number of moments that struck me while visiting Hiroshima in January 2022, but while the main exhibitions of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum were very provoking, I was especially captivated by a special exhibit at the end of the museum, near the gift shop. It appeared fairly new, and it primarily displayed everyday objects found in the destruction left by the bomb, items donated by local residents. There were clusters of melted glass bottles, shards of pottery, heat-blasted teapots, ink bottles, cosmetics containers, and other assorted objects.

I was greeted by a question at the exhibit entrance, “Did people wear make-up even during the war?” While the experience wasn’t as harrowing as the bloodied clothes or battered sentimental belongings displayed in the upper levels of the museum, I was struck by this more mundane exhibit’s concluding statement. While seeing all of these ordinary objects as evidence of the lives the atomic bomb affected, the statement speculates that we might be compelled to react with anger. However, it follows up with a different resolution, saying “our mission is not turning this anger into hate but converting it into an energy to create a world where everyone can live happily.” It seemed a little hopeful, even constructive, and left me with more to ponder about the atomic bomb’s deeper and more profound impacts on humanity.

Dianne is a fourth-year ALT from Southern California and the current Assistant Head Editor of CONNECT Magazine. She is also the Municipal Liaison of the Asia:Japan:Elsewhere region for NaNoWriMo.org and is haphazardly preparing to cobble together another novel about animal people this November.

Chloe Holm (Ehime)

When I arrived in Hiroshima, the first thing I noticed was the quiet. Hiroshima is a sprawling city of 1.1 million people, but it feels a little quieter than other major metropolitan areas in Japan. I came with a few tourist sites in mind, mainly the Atomic Bomb Dome, the Peace Memorial Park, and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Seeing the Atomic Bomb Dome felt surreal. I knew the ruins were an important part of history, but in person, the structure felt stuck in time, a tragedy amid the normal city bustle.

One site I originally had not planned to visit was the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall. I stumbled upon it, and, when entering, the space inside immediately captured the feeling of past tragedy. The immediate path beyond the memorial’s entrance steadily dipped into the underground, the starkly white walls gradually rising above as I descended deeper below into the memorial. Soon, the hall became a vast vertical space, with a clock in the center saying 8:15 a.m., the time the atomic bombs fell. Plastered on the walls were the names of victims from different neighborhoods. The open space and the lonely clock in the center made the hall feel hollow and somber; it felt clean and respectful, but a heaviness weighed on my trip to the ground, surrounded by the walls of deceased names.

There was a deafening silence in that space. It spoke louder than any cityscape could.

Chloe Holm is a first-year ALT living in Ehime. She is the CONNECT Magazine Travel Section Editor and likes DnD, Stranger Things, and poetry.

Marco Oliveros (Tokushima)

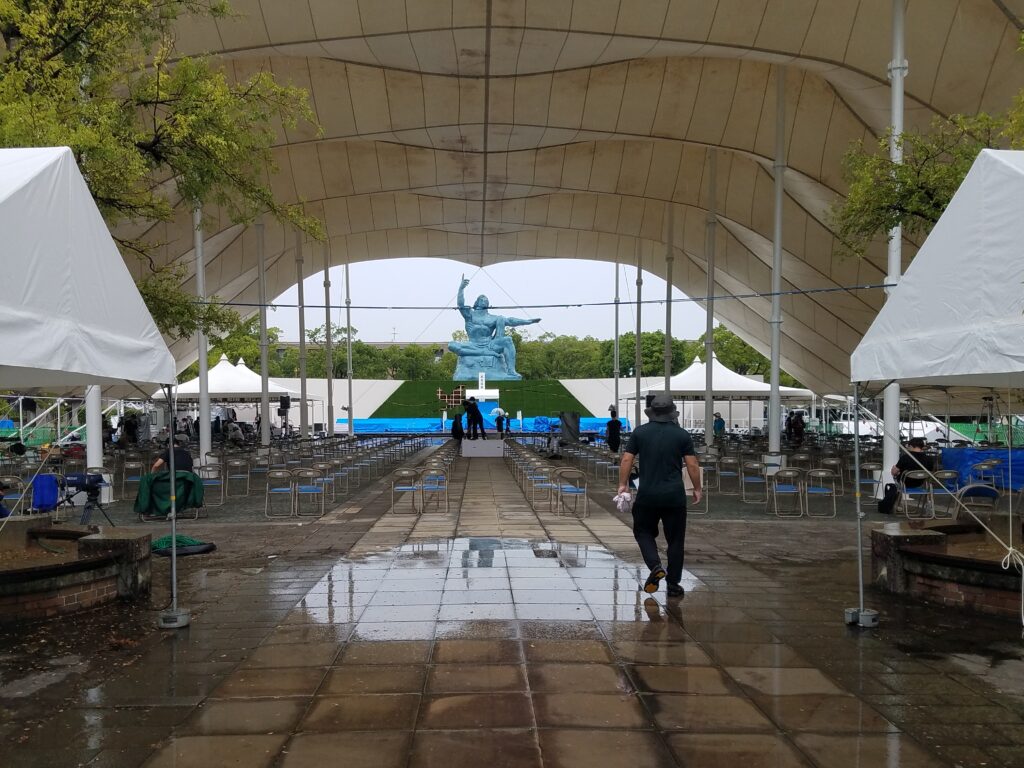

By complete coincidence, I ended up traveling to Nagasaki during the anniversary of its atomic bombing. Somber ceremonies cropped up near memorial markers. Drinks (sake especially) aren’t uncommon offerings at holy sites and gravestones in Japan, but the copious number of water bottles made me think there was some special meaning there.

As a history enthusiast, I’d like to say I’m a little more informed than the average person about how devastating the atomic bombings were, but until I visited the Atomic Bomb Museum, it escaped me the effect those bombs had on the weather. Nagasaki was bombed on a cloudy day, and not long after, an ominous black rain fell. Rumor quickly spread among survivors that they shouldn’t expose themselves to that rain under any circumstances, let alone drink it.

The rain was irradiated poison—it tears the body apart from the inside if consumed—but at the same time, the city just suffered a scorching, and there was little safe water to go around. Dehydrated and badly burned children begged their parents for water, and many parents denied them due to the rumors. Many kids died anyway, in agony, their parents left wracked by grief and guilt . . . Could letting them drink have saved them? Perhaps it could have been a last small comfort.

When I connected the dots from agonizing thirst then to the water bottles at the memorials now, it really hit me. Japanese parents, even now, are mourning.

Marco is a fifth-year ALT in Tokushima and the current Culture Section Editor for CONNECT. He likes history, and thinks sad history is worth learning, too.