Where to start your journey into Japan’s iconic horror franchise

This article originally appeared in the October 2022 issue of CONNECT.

Marco Cian (Hyogo)

Ring is an iconic work of horror, kicking off the J-Horror boom and inspiring a slew of imitators, fan works, and adaptations. However, it’s because of this slew that it can be difficult for newcomers to get into the story, as they trip over the basic question “Where should I start?” The obvious answer is “the beginning,” but which beginning? The original book? The TV movie? The theatrical film? The American remake? Which is the best entry point for someone trying to get into Ring, when each of these works is unique and has their own strengths and weaknesses?

The best lens to view this question through is Ring’s iconic “monster,” Sadako Yamamura. Despite being as famous as Freddy or Jason, Sadako is wildly different depending on what version of her story you encounter. And since these differences reflect the larger differences between the Ring iterations, getting an idea of Sadako will give you an idea of what you’ll get out of each tale.

Spoilers ahead for each Ring adaptation.

Ring (1991 novel)

When reporter Kazuyuki Asakawa learns of the mysterious, simultaneous deaths of four teenagers, he investigates and finds a cursed video tape, which tells him he has seven days to live after watching it. There is a way to avoid his death, but the part of the tape that says this was taped over by the teens, leaving Asakawa in the dark on how to survive. Enlisting the aid of his eccentric friend Ryūji Takayama, Asakawa tries to learn more about the tape, and what turned the mysterious girl Sadako Yamamura into a vengeful wraith.

Because Ring is a novel, and the product of a single creative, it has the most singular vision of all the pieces of Ring media. Suzuki evokes haunting mysteries like those of M. R. James, but in the style of the trashy horror paperbacks that glutted bookshelves from the `70s to `90s. If you’re a fan of those paperbacks from hell, you should enjoy Ring well enough. However, this focused vision is also the book’s greatest weakness. Several passages are just Suzuki using his characters to discuss his own interests or air his personal gripes, which takes a darker turn as we learn more about Sadako.

In Ring, Sadako was born with Hollywood androgen insensitivity syndrome (which is a bit different from actual AIS for narrative purposes), where, despite looking like a beautiful woman, Sadako possessed a male sex organ, which Suzuki uses as evidence that she was born unnatural, a mistake. This is also why her would-be rapist killed her (and was justified in doing so, according to Suzuki), because she “tricked” him. And the reason she became vengeful was that, as an intersex person, Sadako couldn’t have children. But all women need children. Without them, their lives are incomplete. So Sadako’s inability to conceive led her to become evil. This sort of luridness is par for the course for the trashy paperback environment Ring sprang from, but may be off-putting to many readers, and as you’ll see, most adaptations give Sadako a completely different backstory.

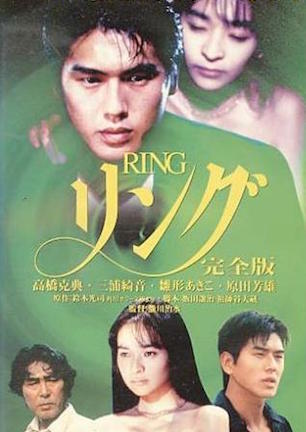

Ring (1995 film)

While the TV movie is the most faithful adaptation of the book, its story is streamlined to be more digestible, and its characters are altered to be much nicer, especially Sadako.

While Sadako in this film is still intersex, it’s made clear that her vengefulness stems not from some inherent unnaturalness, but from how the world treated her for her condition. Sadako was someone very desperate to be loved, but who was shunned and hated by society. So while she is still a monster, she was made, not born, with the movie urging the viewer to not be so harsh in how we treat people who are different. Indeed, Sadako’s ghost explicitly tells Asakawa how to avoid the curse simply because he shows her the kindness she always sought.

Viewers might still dislike how this is a story about LGBTQ+ misery, even if it’s sympathetic to LGBTQ+ people. However, if you want a general idea of the original story but don’t want to listen to Suzuki’s soliloquies, the TV movie should satisfy you.

Ring (1998 film)

Ring is a fairly faithful adaptation in terms of plot. However, its tone and characterization are so different that it barely resembles its source material. Asakawa and Ryuji go from platonic friends to a divorced couple, with their interactions no longer friendly banter but stilted awkwardness. And rather than a ticking clock mystery, the `98 movie is steeped in a creeping dread, as Asakawa and Ryuji try to not give into hopelessness over Sadako’s curse.

This is easily the most monstrous Sadako, with her appearance based on onryo wraiths and her never speaking or showing her face. Instead of killing in self-defense, this Sadako kills anyone who annoys her, and doesn’t tell people how to escape her curse. While the intersex angle has been dropped from this Sadako, the idea that she was born unnatural remains. One cannot reason with Sadako, because she is less a person than a force of evil and vengeance.

This is the movie that started the J-Horror fad in the West, and while some viewers might find it not living up to the hype, it’s refreshingly different from most Western horror, in that the monster cannot be defeated or outsmarted, but must be sated. You have to continue the ring, and there’s no way out of it.

The Ring (2002 film)

The Ring takes a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it scene from the `98 film and expands it into a major theme. Asakawa’s son was briefly shown to be a latchkey kid because of her work schedule, and Rachel Keller (Asakawa’s counterpart) must find a way to balance her work with her duties as a parent.

In this, Sadako (now Samara) was probably the progeny of Deep Ones like in the `98 movie, but instead of being born evil, she was simply born with psychic powers she couldn’t control. When dealing with these powers became too difficult for her parents, they murdered her. The Ring focuses on parents and children, how children can be born physically disabled, mentally challenged, or just not what we expected. But as parents, we have a duty to raise and love our children no matter how difficult they are, because we brought them into this world.

Unfortunately, this creates a problem for the 2002 movie, because unlike all the other Sadakos, Samara has no reason to continue the curse after being laid to rest. She wasn’t driven by a need to reproduce like book-Sadako, she wasn’t scorned and hated by the world like TV-Sadako, and she’s not a monstrous force of nature like film-Sadako. She was a young girl who couldn’t control her powers and just wanted someone to listen to her. So the movie has to pull an unconvincing twist so we can have the same ending as all other Ring adaptations, despite that ending making no sense for the movie we’ve seen up to that point. The Ring is unusual for being an American remake where the story would have been better if they’d changed more, instead of less, and will thus probably leave viewers cold after watching.

Marco Cian is a second-year ALT in Toyooka, Hyogo. He couldn’t make it through the South Korean Ring movie. The Ryuji analogue was just too insufferable. He also found Spiral to be a wonderful unintentional comedy. Seriously, “You smell like a corpse!”? Hilarious. He reads a lot, particularly fantasy, and he even wrote his own fantasy novel, which you can find on his Substack here (new chapters every other week) or his blog here.

![CONNECT ART ISSUE 2024 SUBMISSIONS [CLOSED]](https://connect.ajet.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ARTISSUE-INSTA-600x500.png)