This article originally featured in the February 2022 issue of Connect.

A Popular Traditional German Song in Japan

Marco Oliveros (Tokushima)

Hands tucked in warm coat pockets, scarf wrapped around my neck, I climb down the mountainside Japanese shrine in my neighborhood as the winter sun dims into the horizon. My breath is a condensed white as I exhale down already dark stone stairs. Clocks everywhere strike 6:00 p.m., and the loudspeakers around Naruto City play a song from, oddly enough, Germany: Ode to Joy. And on it plays, in every season of every day, from winter, spring, summer, fall, and winter, this hopeful ode.

It’s kind of weird music to hear played to mark the beginning of evening, but Ode to Joy is a song with an interesting history in Japan, and a remarkable past in Naruto, Tokushima. Inspired by the poem of the same name by German poet and philosopher Friedrich Schiller, German composer and pianist Ludwig von Beethoven wrote up an whole section in his Ninth Symphony as an homage to it, turning the words of the poem into lyrics for his music.

Ode to Joy’s humanistic message of freude, brotherhood, and goodwill to all fits fairly neatly with the Christmas vibe, even if it wasn’t explicitly written to be a Christmas song. December does happen to be Beethoven’s birth month. Today in Japan, Ode to Joy and Beethoven’s Ninth is sung and played in the choruses and orchestras of Japanese schools and concert halls of every month, but especially during December, especially in Osaka-jo Hall with its 10,000 person daiku concerts, especially at the year’s end daiku performances in Naruto.

How did Ode to Joy get to be so famous in Japan? Well, it first had to do with war. During World War I, as a military ally of the British Empire via the Anglo-Japanese Alliance (and by extension, the Allied Powers), Japan attacked and captured German holdings all across the Asia-Pacific—including the German-held Chinese city of Qingdao. German soldiers turned into prisoners of war, and the Japanese interned these German POWs in camps all over Japan. One of them was the Bando POW Camp in Tokushima Prefecture.

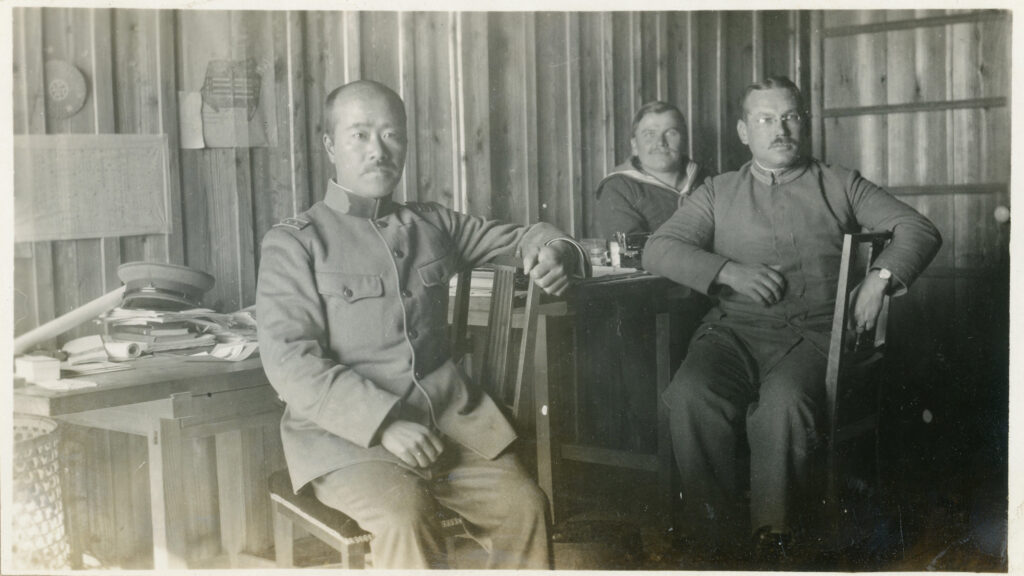

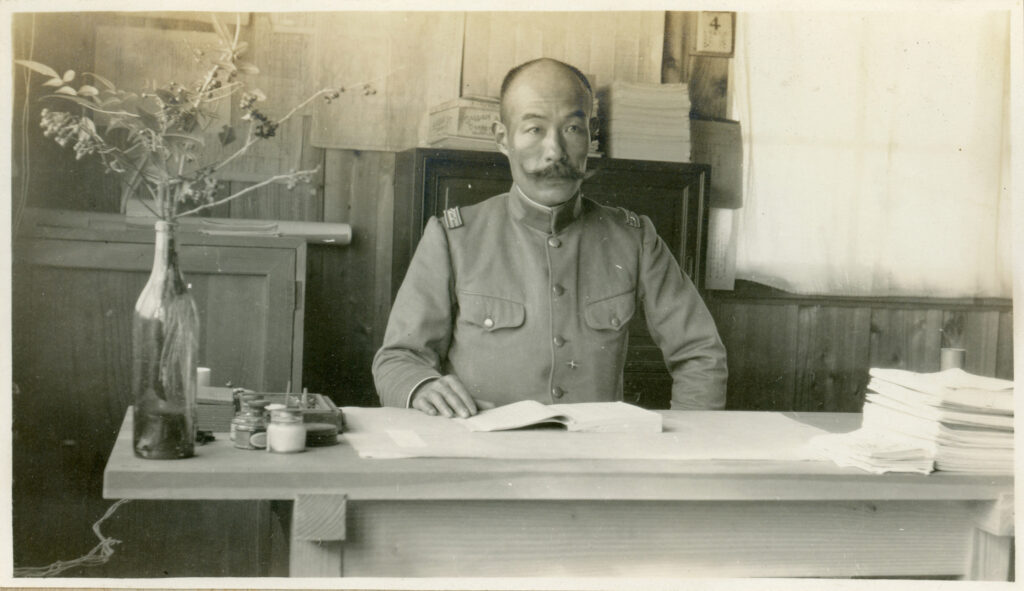

Not yet were the days of Japan’s WWII-era concentration camps, with its myriad accounts of horrors visited upon the POWs therein, but there wasn’t any guarantee that these German POWs of the First World War would be treated especially well either. One wildly notable exception to these expectations was the Bando POW Camp, whose commandant, Toyohisa Matsue, bid his German guests to enjoy their stay until peace returned, so long as they didn’t cause trouble or leave the camp without his permission.

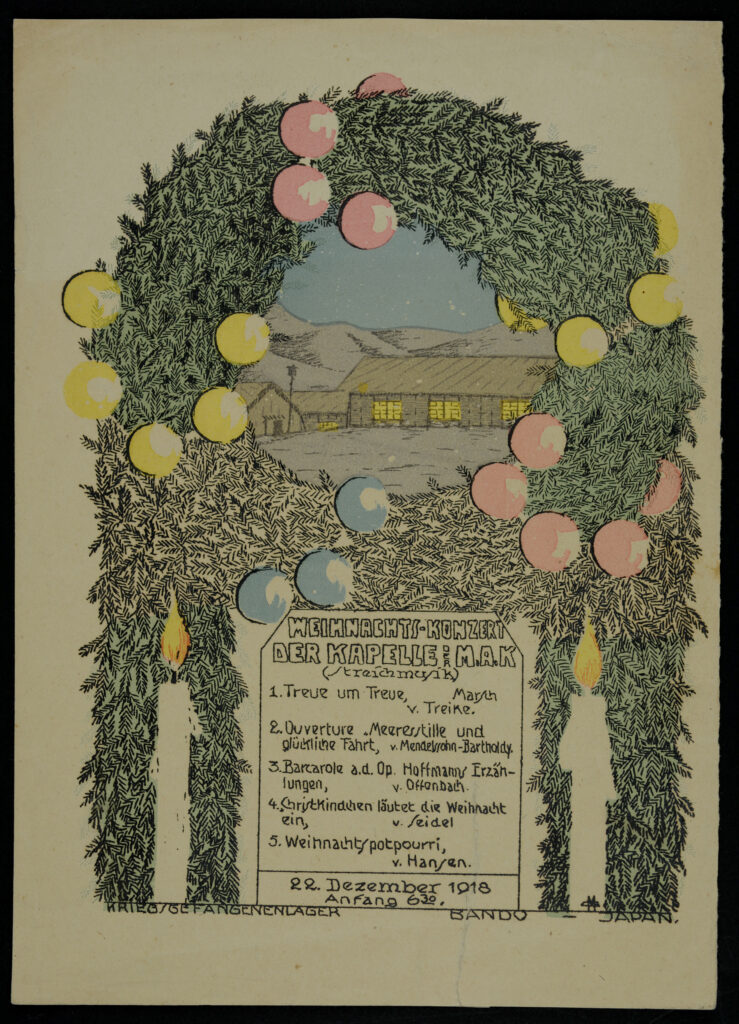

Many of the Germans sent to Bando weren’t crude military grunts, but men of various skills, trades, learning, and interests, and the camp commandant allowed them the freedom and even some resources to ply them. They grew crops, baked bread, made cheese, brewed beer, built furniture, swam in pools, played sports, sketched pictures, published newspapers, constructed a bridge, practiced instruments, and much more. When some of his German guests passed away to natural causes, the commandant allowed the survivors to hold funerals for them. A cenotaph monument commemorating the German dead stands watch now, cared for today by Japanese locals.

By war’s end, when the Germans were finally permitted to return back home, some decided to stay and make Japan and Tokushima their new one.

But before war’s end, these grateful German POW-guests of Bando, with the commandant’s leave, decided to organize concerts for the Japanese public. Interactions and exchange between curious Japanese locals and the interned Germans had occurred before and would occur in-between. However, it’s with these concerts and a certain song played during them that these Germans left their most memorable impact on Japan. Overcoming cultural differences and even the fact there was war going on between their two countries, the Germans of Bando played a concert of humanism for the Japanese; a song of freude, brotherhood, and goodwill to all; a Symphony numbered Ninth by Beethoven; an Ode to Joy.

Tokushima would be the first place in Japan the Ninth Symphony would be played live. Japanese concert renditions of the Ninth would later be called daiku in Japanese, and its popularity would continue to spread all over the country and into the decades beyond.

After both World Wars, the city of Naruto would later integrate the Bando area into its jurisdiction. The city has since taken active efforts to promote the intercultural legacy left behind by the Bando POW Camp. Blessed by both the Japanese and German governments, the Naruto German House (or doitsukan in Japanese) was established over the former camp grounds to serve as a museum and a center of cultural exchange between Japan and Germany. Naruto currently enjoys a sister city relationship with the German city of Lüneburg.

Little of the physical barracks the Germans lived in still survives, but dioramas of their living quarters along with other exhibits and artifacts detailing life at the camp can be viewed at the Naruto German House. The bridge the Germans built still stands, and so does the cenotaph monument dedicated to those who died there. During pre-COVID times, the city would put on 600-person Naruto-Daiku, or Naruto-Ninth, concerts in December. And in every season of every day, from winter, spring, summer, fall, and winter once again, it plays.

Clocks everywhere strike 6:00 p.m. as I head back from my regular winter walk down the mountain shrine, scarf wrapped around neck, hands stuffed into coat pockets. The loudspeakers of my neighborhood in Naruto come alive to a familiar frequency, an Ode of Joy, bidding me in the dark, welcoming me to warmth and home.

Marco is a fourth-year ALT and the current Culture Section Editor for [CONNECT]. Living up to his certain Italian explorer namesake, he’s traveled to over 25 prefectures in Japan so far, primarily to comb over places of historical significance. He really likes history.

Sources: