This article originally featured in the October 2021 issue of Connect.

Jake Davis (Okayama)

Before coming to my current town of Nagi, I hadn’t the faintest idea of kabuki, let alone its history or appeal. I’d imagine that many foreigners residing in Japan or overseas may have briefly seen kabuki on television, in a picture somewhere, or perhaps heard iconic kabuki sounds from Japanese anime and video games. Apart from these sources, I had no idea what it actually was, and if I’m being honest, I wasn’t deeply interested in finding out more, especially when it seemed like such a niche area of Japanese culture, similar to Shakespeare. However, I was placed by JET in a town that prides itself on its preservation of kabuki traditions since the Edo period (1603-1867). After being asked by a local kabuki expert if I would like to give Yokozen Kabuki a go, I knew it would have been a big mistake to turn it down.

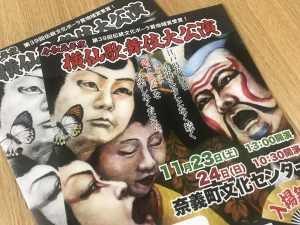

Yokozen Kabuki is Nagi’s amateur kabuki theatre tradition. It differs from other kabuki in that it is performed entirely by locals, of whom anyone can take part. Kabuki historically became restricted to grown men due to the Edo shogunate, as it was believed that the use of female performers could corrupt public morals. To this day, professional kabuki continues to be male restricted out of custom. More on kabuki in general can be read in this [CONNECT] article here. However, due in part to local actor shortages, for the majority of its existence, everyone, including women and children, has been allowed to perform in Yokozen Kabuki. Yokozen Kabuki was a pastime for Nagi’s local farmers and flourished during the twentieth century. To preserve their local tradition, in 1996, the local Nagi government established the Children’s Kabuki Workshop. Supported today by the Yokozen Kabuki Preservation Society, local children at the Workshop not only learn acting, but also become familiar with the instruments, props, and makeup used in kabuki. These children then perform before a discerning crowd during the annual two-day show in late November. Videos on Yokozen Kabuki can be watched here.

I was asked to join a small group of five other locals, including a mother and her three primary school aged children, in a series of short skits between scenes in one of the main performances. I went to Yokozen Kabuki rehearsals, known as keiko, which at first involved our small group sitting down on the stage with one of the local kabuki experts, going through a vertically-written script and discussing the characters. Despite being able to grasp everyday Japanese, the script language was completely different to what I was used to—not to mention the unique way one’s character lines are performed. We got together to practice once a week for roughly two months. I realized quite quickly that, especially as a non-native Japanese speaker, I would be better off using my phone to record an expert reading my lines and using that audio to practice at home by shadowing it.

When the day of the performance came in late November, we had to be there a couple of hours before our performance in order to get ready. During that time, I bumped into some familiar faces who were excited to hear that I would be performing and gave me some last-minute encouragement. Upon entering the costume room, I saw performers having their makeup applied by hand by local elders, being dressed, and getting wigs placed firmly on their heads, all according to their roles. The makeup doesn’t come off easily due to the horse oil used, and I remember it taking about twenty minutes to remove it afterwards. It was definitely worth it for the experience though—plus it made for some cool photos to show the family and friends back home in Australia.

Prior to walking on stage, our small group was waiting in a side room next to the stage, visible only to a few people in the front of the audience. I could hear whispers from some local elders, curious about me performing their local Yokozen Kabuki. As we walked on stage, I felt nervous because I wanted to do my best to respect the local traditions while hopefully impressing people. Because of all of the practice that I had done though, and because I was performing in a group that I had become quite close to during rehearsals, I also felt confident. I can’t say that my acting was great by any standard, but I was thrilled that I was able to remember all of my lines, including the long ones.

The skits I performed were bits of comic relief, and the audience seemed to enjoy them. At the end, we bowed on the main stage as ohineri (small paper-wrapped money offerings, often coins) were hurled onto it by the audience. After we exited the stage, we made our way back to the costume room, though not before getting some quick photos in the lobby and chatting to some locals who had watched the show.

Originally, when I heard about the strictness of professional kabuki, such as only men being allowed to perform, I was surprised that Nagi’s local Yokozen Kabuki was so open to having a foreigner perform. I remember several elderly people coming up to me, smiling while telling me that I did a good job. That, along with the shock of almost getting hit with coin bags on stage, calmed my nerves completely, and I felt proud of myself for having decided to take part. I think it must have also been a memorable experience for the locals to have a foreigner involved in the process. I bumped into one of the kids from my group a few months later when visiting the school. She was really excited to see me again.

Shortly after, I was asked to check the script of an English kabuki performance that a local Saturday English club, mostly of elderly women, was going to rehearse and perform for the winter show in February. As you could probably guess, the script’s English would be considered quite unnatural even after multiple checks, similar to trying to translate a Shakespearean play into Japanese. However, I felt that despite the impossible nature of translating a kabuki script perfectly into English, after some checks with an expert, we felt that the English club’s final script was acceptable for what it was—something aimed at bringing the wonders of Japanese culture to a wider audience. By having a native speaker check the script and give feedback, the members of the English club were much more motivated to give it their best, without taking it so seriously that they couldn’t enjoy themselves.

I ultimately ended up participating in the English club’s play, performing as the famous Lady Shizuka in a condensed version of Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Blossom Trees. I had fewer lines, and the English was definitely easier to remember. However, learning to walk elegantly with one giant foot in front of the other, while being squeezed into a kimono for over an hour and also wearing the heaviest wig that they had available, was a challenge. Despite being far too tall for the role, with a bit of practice, I was able to walk without tripping over my own feet, and thanks to the makeup artists and costume staff, my mum was pleased to see how pretty her hypothetical daughter could have been.

I sincerely believe that, when looking back on your time in Japan, it is unexpected opportunities like these that help to make it all worthwhile. Of course, with all of the odd requests and invitations that you may receive, you shouldn’t take on more than you can handle. It’s definitely important to say no sometimes, and it’s fine to say that you need time to think something over. However, by getting involved and saying yes to opportunities, including things that may take you out of your comfort zone, you will not only have a memorable experience and strengthen your connection to Japan, but also have a very real and significant impact on your local community.

Jake Davis is a fourth-year Coordinator for International Relations (CIR) from Perth, Australia, based in Nagi, Okayama. He spends his time studying Japanese, traveling (when possible), and is working towards becoming a primary school teacher in Australia.