This article originally featured in the May 2020 issue of Connect.

David Atti (Chiba)

“I think I want to try judo.”

I casually uttered those words to Mr. Sakai, the secretary at my elementary school. He was a good person to talk to about judo since he had been a judoka himself.

Mr. Sakai paused to look at me for a minute before starting to make calls like a stockbroker on Wall Street. He quickly arranged for me to meet Sunaga-sensei, the local fire chief and head instructor of Kamogawa Judo Club. So I went to the dojo, and on my first day, I was presented with a gift: my uniform.

The uniform formerly belonged to Sunaga-sensei’s son, and it was practically a dojo relic since the fire chief’s name was stitched in the lapel. I stared at the judogi that had been passed down to me. Kamogawa’s characters were boldly embroidered in black on the right side. The inaka judo club welcomed its newest white belt.

The uniform formerly belonged to Sunaga-sensei’s son, and it was practically a dojo relic since the fire chief’s name was stitched in the lapel. I stared at the judogi that had been passed down to me. Kamogawa’s characters were boldly embroidered in black on the right side. The inaka judo club welcomed its newest white belt.

Sunaga-sensei was explaining to me that the dojo’s members were primarily firefighters and students when suddenly, one of the black belts roared “HEY! HEY! HEY!” as he sprinted into the dojo. This judoka was full of warmth and charisma. Sunaga-sensei cracked a smile before introducing me to Kazu, a 29-year-old fireman and former champion of Chiba Prefecture.

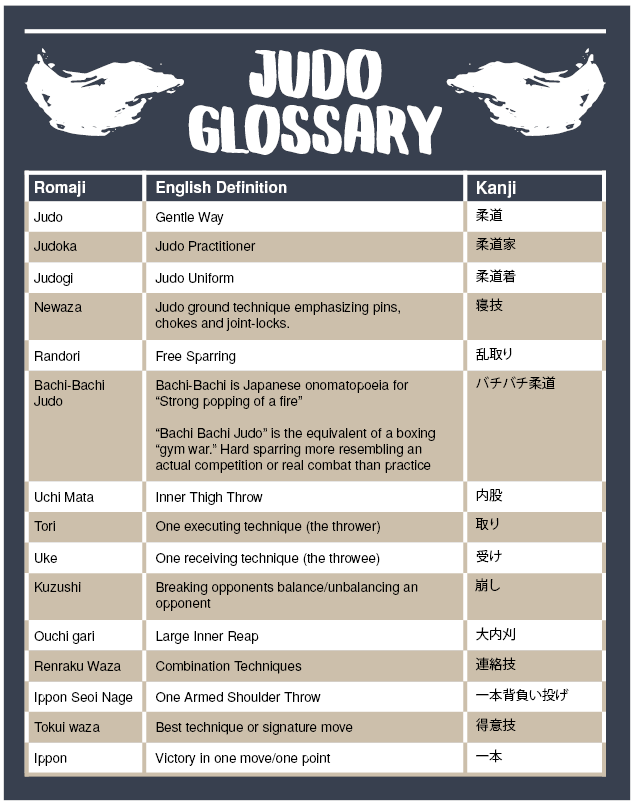

I immediately noticed his cauliflower ears, forged from years of newaza (ground technique(s)). He was in great physical condition, standing about 5 feet 6 inches and weighing a lean 68 kilograms. Sunaga-sensei said he’d like us to practice randori (free sparring) together. On the mat, Kazu quickly demonstrated to me what he referred to as “bachi bachi judo,” throwing me up and down the dojo at will. When I established a grip and tried my best to throw him, he’d tease me, shouting, “hoshii” (close or almost) with a big grin on his face before slamming me onto the mat again. I staggered to get to my feet with the wind still knocked out of me. Meanwhile, Kazu was already on his second victory lap around the dojo again howling, “HEY! HEY! HEY!”

I immediately noticed his cauliflower ears, forged from years of newaza (ground technique(s)). He was in great physical condition, standing about 5 feet 6 inches and weighing a lean 68 kilograms. Sunaga-sensei said he’d like us to practice randori (free sparring) together. On the mat, Kazu quickly demonstrated to me what he referred to as “bachi bachi judo,” throwing me up and down the dojo at will. When I established a grip and tried my best to throw him, he’d tease me, shouting, “hoshii” (close or almost) with a big grin on his face before slamming me onto the mat again. I staggered to get to my feet with the wind still knocked out of me. Meanwhile, Kazu was already on his second victory lap around the dojo again howling, “HEY! HEY! HEY!”

After my first taste of randori, I couldn’t imagine how anyone could refer to judo as the “gentle way.” When I think back on my first day, I showed two things if nothing else: my ignorance of the Japanese language and heart. Over time, this would prove to be a comical and perilous combination.

But Kazu eventually decided to take me under his wing after many more one-sided randori sessions, and all the black belts were excited when I told them I wanted to learn uchi mata (inner thigh throw). I was in the right place to do so. Everyone praised Sunaga-sensei as an “uchi mata master.” Uchi mata is considered one of the more complex throws in judo as the timing needs to be perfect. Sunaga-sensei acted as tori and requested that Nori-san serve as his uke. Nori-san, one of many firemen in the dojo, resembled a Japanese Terry Crews due to his shaved head and “dynamite body.” After witnessing the fire chief throw around the much larger man with ease, I thought I’d give uchi mata a try. I decided that this technique would be my main focus.

Kuzushi

In The Art of War, Sun Tzu writes, “All warfare is based on deception.” I started to understand this more after studying judo. I tried desperately to throw everyone with my uchi mata, but my attack was too transparent. In boxing terms, I felt like a crude slugger throwing wild haymakers against a slick counter-puncher. I telegraphed my throw in every way imaginable. Kazu joked that every time I’d try to throw him, my eyes would pop out of my head like that old-time cartoon wolf.

Tamaru-sensei, a fourth-degree blackbelt and absolute bear of a man, sought to remedy the situation with something he called kuzushi—the practice of “breaking your opponent’s balance” before throwing them. Tamaru-sensei grabbed my judogi and “broke my balance” with a forward throw, ouchi gari. I stumbled backwards on to my heels, fighting to stay on my feet. As I struggled to regain my footing, Tamaru-sensei abruptly yanked me forward on to my tippy toes and launched me into the air with a proper uchi mata. Suddenly, I was airborne. Sailing through the air, I couldn’t help but wonder how big of a hole my body would make when I hit the floor. Luckily, Tamaru-sensei kindly pulled up on my sleeve and lapel at the last minute so the impact wouldn’t cripple me.

Tamaru-sensei, a fourth-degree blackbelt and absolute bear of a man, sought to remedy the situation with something he called kuzushi—the practice of “breaking your opponent’s balance” before throwing them. Tamaru-sensei grabbed my judogi and “broke my balance” with a forward throw, ouchi gari. I stumbled backwards on to my heels, fighting to stay on my feet. As I struggled to regain my footing, Tamaru-sensei abruptly yanked me forward on to my tippy toes and launched me into the air with a proper uchi mata. Suddenly, I was airborne. Sailing through the air, I couldn’t help but wonder how big of a hole my body would make when I hit the floor. Luckily, Tamaru-sensei kindly pulled up on my sleeve and lapel at the last minute so the impact wouldn’t cripple me.

He led me to a white board in the dojo to further illustrate his point. He imparted to me the need to use kuzushi in combinations. Tamaru-sensei broke down the combination he had just used on me. “Ouchi gari, mae!” (large-inner reap, forward!) he asserted while pointing to a small circular magnet on the white board. Next, he slapped a larger magnet on the white board and firmly said, “uchi mata, ushiro!” (inner thigh throw, back!). The blackbelt picked up a dry-erase marker and drew a line connecting the two magnets representing my new combination. These types of deceptive combinations effectively utilize kuzushi and are referred to in Japanese as “renraku waza.” To really ensure I was getting all this, Tamaru-sensei smiled as he concluded his lecture in English, “Do you understand?” I couldn’t help but laugh as I replied in my native tongue, “Yes, I understand!”

Tamaru-sensei’s lesson really resonated with me. I boxed for years as an amateur in the U.S. and I was starting to notice an overlap between the two combat sports. In my opinion, in the same way the pugilist sets up his knockout blow with a jab, the judoka employs kuzushi before a big throw. It is essential in both disciplines to disrupt your opponent’s rhythm by unbalancing them before following up with stronger attacks. If a boxer neglects the jab and only throws power punches, the other fighter can likely see them coming from a mile away. This approach is predictable and exposes the fighter to the risk of being countered. This was the same problem I was having during randori. Judokas and boxers both get to the level where they can effortlessly string together combinations from all angles by varying their attack. I tried to apply these concepts effectively using “deception” in my judo.

Gaman Shite

Gaman Shite

Six months or so into my first year on JET, my Japanese gradually improved along with my judo, although both were still cringeworthy at best. I started asking Tamaru-sensei, “What do I do during newaza in a judo match?” Tamaru-sensei gave me a detailed explanation in Japanese but I understood little more than “gaman shite.” This expression can mean “to be patient” or “to endure” depending on the context. One day, Tamaru-sensei was shocked to see me trying to “endure” a choke for too long. He quickly stepped in and asked, “Why don’t you just tapout?” I responded like Mifune Toshiro in a Kurosawa epic, “Gaman!” I barked. Tamaru-sensei erupted in laughter, swiftly cutting down all my samurai fantasies. After regaining his composure, he explained that during newaza, if the contestants are inactive on the ground, the referee will stand them up in a matter of seconds. “If that’s the case, just be patient!” he said before reproaching me, “You don’t endure a choke or an armbar!” My failed attempt at stoicism has since become one of Tamaru-sensei’s favorite stories to tell at the judo club’s wild drinking parties.

Tokui Waza

Tokui Waza

I practiced uchi mata for over a year, struggling to land it consistently during randori. I was beaten from pillar to post every week as Tamaru-sensei and Sunaga-sensei looked on, shouting instructions to me. My senpai started to embrace me more, making a great effort to explain uchi mata’s mechanics in English when I couldn’t understand his Japanese. One of Kazu’s best throws was “ippon seoi nage” (one-armed shoulder throw), which he had used to throw me countless times during our “bachi bachi judo” sessions. I rarely practiced this throw but decided to go for it one day during randori, doing my best to emulate Kazu’s movement and timing.

Everyone (including myself) was shocked when I pulled it off. Kazu told me that in our year of doing randori together this was the first throw I had truly earned (He even let out his customary “HEY HEY HEY!” saluting my progress). Sunaga-sensei and Tamaru-sensei told me I had finally found my “tokui waza” (signature move). Everyone was relieved that all those randori sessions weren’t just senseless violence, and those who had helped me “find my throw” assured me this was just the beginning. But I couldn’t afford to rest on my laurels for long—I was told our “bachi bachi judo” sessions would “level up” from that day forward.

The feeling of executing a perfect throw is surreal. If a judoka can execute a perfect throw during competition, they win by ippon (victory in one move) automatically ending the match. Until that moment, randori had felt laborious and stiff to me. A contest of strength against strength. When I was finally able to throw an opponent properly, it felt fluid and relaxed—almost effortless. It even sounded different. I started to compete and win via ippon using my new favorite throw. One day before practice, a shy chubby-cheeked elementary student approached me. His wide smile was missing a few teeth. I was incredulous when he asked that I teach him ippon seoi nage. This marked the start of my understanding of judo as the “gentle way.”

Photos: David Atti

Sources:

https://judoinfo.com/terms/

https://www.judo-ch.jp/english/dictionary/

https://jisho.org

http://classics.mit.edu/Tzu/artwar.html

https://www.tofugu.com/japanese/japanese-onomatopoeia/

David Atti is currently a second-year JET in Kamogawa City, Chiba Prefecture. When not on the mats, he enjoys travelling and reading about the Sengoku Jidai. David graduated from SUNY Geneseo with a degree in American Studies before coming to Japan.