This article originally featured in the March 2020 issue of Connect.

Rachel Fagundes (Okayama) Photos: Wikimedia Commons & Rachel Fagundes

Kabuki theater, with its striking face paint, wild wigs, and bold poses, has become an iconic image of Japan internationally. However, the art form is not always well understood abroad, or even by Japanese people. The heightened and archaic language can make the dialogue difficult to access even for native Japanese speakers, and its stylized form is an extreme departure from the more naturalistic style of acting preferred in the west. Nonetheless, this unique form of theater is a delight, and well worth experiencing if you get the chance.

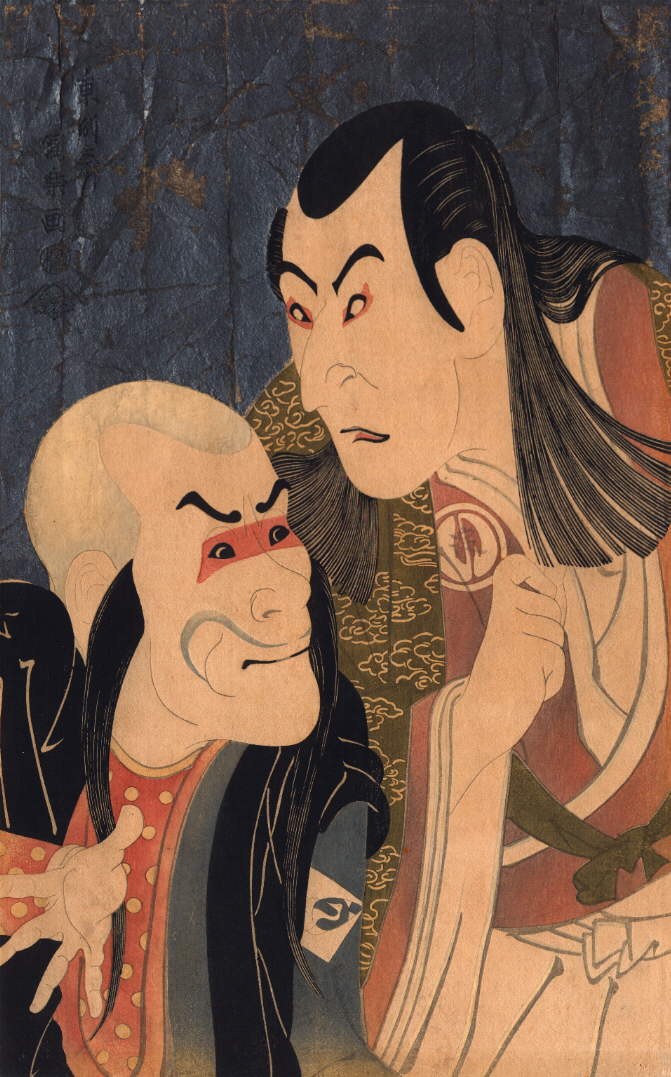

Kabuki, which derives its name from the Japanese word for “bizarre” or “outlandish,” is currently the most popular and well known of Japan’s traditional theater forms. Its plays usually have a five act structure and are performed exclusively by male actors, appearing in both male and female roles. Men playing female characters are known as onnagata and have developed highly stylized posture, gestures, and mannerisms to capture the ideal of alluring feminine beauty in their performances. In fact, all of the roles in kabuki are quite stylized. Audiences can spot certain character archetypes by their costumes and makeup. The actors paint their faces stark white and exaggerate their features using colorful paint that not only made their features easy to see in the dim Edo-era theaters, but also communicates their character’s social standing and temperament. Wild, blustering warriors would be made up very differently from thoughtful, delicate aristocrats or scheming villains. The actors speak in a kind of old, elevated Japanese, somewhat akin to Shakespearean English. They are accompanied by musicians and a narrator, who apparently sings his lines in an even older and less accessible form of Japanese.

Although modern kabuki may include more variation and experimentation, most traditional kabuki falls into one of three main genres: jidaimono (historical dramas), sewamono (domestic melodrama), and shosagoto (dance).

As in noh theater, kabuki acting is passed down in family lines, often from father to son. Kabuki actors will also take on, and pass on, their father’s stage name. Some particular plays are performed only within certain family lines, while the most famous and popular plays are known to all troupes. Kabuki connoisseurs may even delight in comparing how a father and son will interpret the same roles.

If this all sounds a bit dry and formal, you may be surprised to know that kabuki has quite a wild history. It was even seen as a dangerous influence by the Tokugawa Shogunate, which struggled (and generally failed) to contain and regulate kabuki for hundreds of years.

Kabuki was actually founded by a woman, Izumo no Okuni, in 1603. In its early form, kabuki consisted of dancing and short, often funny or provocative, skits performed by women who wore outlandish men’s clothes, sometimes carried swords, and played both male and female characters. This form of kabuki caused a sensation and became wildly popular (until 1629 at least, when it was banned by the shogun on account of being too sexy). The actresses who founded kabuki were then replaced by adolescent boys, who were themselves banned shortly thereafter—also for being too sexy. Eventually, adult male actors took over the roles and were allowed to perform. At this point, kabuki evolved to have less emphasis on dancing and more on narrative and drama.

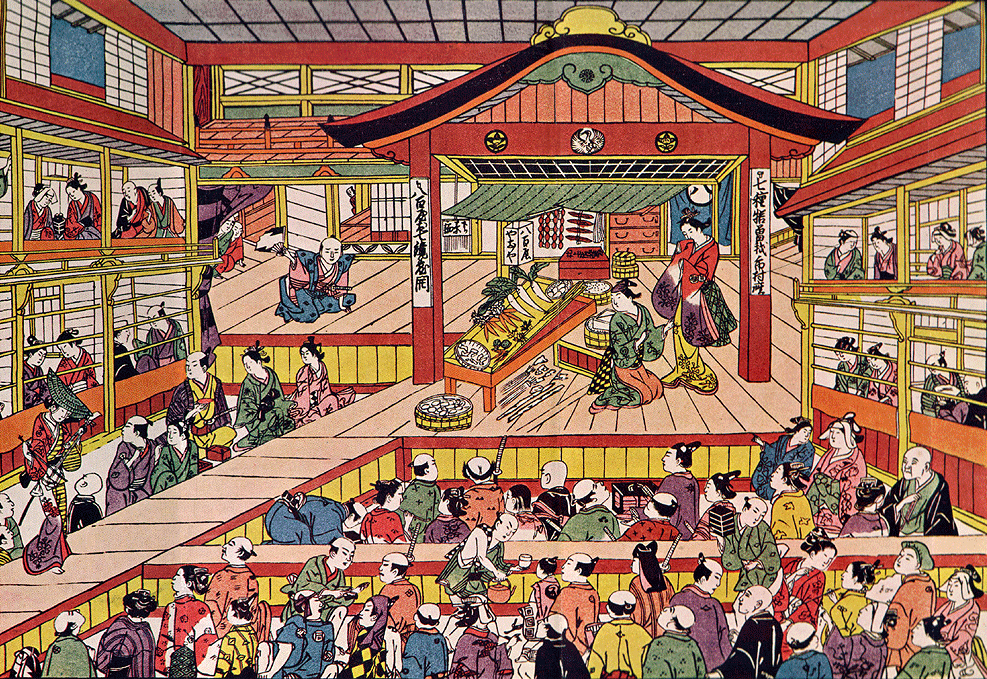

Unlike noh, which was the theater of the upper class, kabuki was the theater of the common people. It flourished throughout Edo’s Golden Age from 1673–1841. Numerous kabuki theaters were built in Edo’s entertainment district, and lively theater districts appeared in Kyoto and Osaka as well. Bunraku puppet theater developed alongside it, and the two art forms frequently borrowed popular scripts and innovations from one another. Many tropes and conventions of the art form were codified during this period, including the act structure and genres. Kabuki also developed into two prominent styles of performance: aragoto (rough style), which is characterized by dramatic mie poses, and bright, stylized kumadori makeup, and wagoto (soft/gentle style) which is more natural.

In the early 1700s innovations in stagecraft included revolving circular platforms built into the floor of the stage, allowing the whole set to revolve for quick and dramatic scene changes. Later, some stages were also built with trapdoors in the floor, and even elaborate flying rigs that allowed actors to float over the crowds in dramatic scenes where clever fox women make daring escapes or deities ascend into the heavens.

Despite being “The Common People’s Theater” and therefore considered inappropriate for the upper class, kabuki remained of interest to a broad swath of Edo society. At the height of its popularity, the kabuki theaters and the tea houses around them became the center of fashion, culture, and social mixing in Edo, and productions would last all day long. Kabuki became a favorite subject of Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, with famous scenes from kabuki plays and portraits of popular kabuki actors selling like hotcakes in the theater district. Oshiguma, face prints of the kabuki actor’s makeup, were also sold on strips of cotton or silk as mementos of their performances. Kabuki actors were so popular that fights could sometimes break out in the theater over their favor, and high ranking nobles snuck into private boxes to see performances, despite being banned off and on from doing so. Kabuki even spread outside major urban centers with local variations becoming popular in some rural towns.

Throughout the Edo period, the Tokugawa Shogunate viewed kabuki as a source of mischief and societal disruption, and fought a losing battle against its popularity and influence. Kabuki actors of Edo were banned from leaving the theater district to give private performances in noble houses; they did so anyway. Onnagata were ordered to adopt deliberately unattractive hairstyles to curb their sexiness; they developed elaborate wigs. Theaters were ordered not to use exquisite fabrics in their costumes, since this would be above their station; these bans were eventually worn down and rescinded. Plays were strictly forbidden from critiquing the government, or depicting contemporary events or political figures; thinly veiled political satires simply changed the character names and setting to that of an earlier historical period.

In 1868 the Tokugawa Shogunate collapsed, the emperor was back in power, and Japan went through a radical transformation from a feudal state to an industrialized nation. The samurai class was gone, but kabuki survived into the Meiji era and saw new innovation and experimentation during this time.

Kabuki was also briefly banned by the American occupying forces after WWII, but it was eventually allowed to return to the stage. Although kabuki struggled somewhat in the postwar period to compete with that advent of television and other modern forms of entertainment, kabuki has been recognized as an important cultural asset was declared by UNESCO to be intangible heritage possessing outstanding universal value.

Kabuki continues to adapt and evolve in the modern era. In addition to still popular classics from the Edo period, new kabuki plays continue to be written, as well as adaptations from sources as varied as Shakespeare plays, Italian operas, and Ghibli movies.

You can enjoy kabuki productions in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka at such venerated theaters as Kabukiza, Minamiza, and Osaka Shochikuza. If you’re lucky, you may even find local kabuki groups performing in the countryside to this day.

Sources:

1. Begin Japanology Kabuki (NHK Documentary)

2.“Bakufu Versus Kabuki,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

3. Wikipedia

Interview with Kabuki Actor Taiki Yokobayashi

After driving through rice fields on tiny, unlit, dirt roads in the dead of night, circling and searching for a location that would obviously scream KABUKI FESTIVAL, I came upon Katsuga Shrine. The locals had been performing kabuki here since the late Edo period, and built a theater behind the shrine to house their annual autumn festival. Dozens of cars were clustered around it, trying to park, jostling to pass each other on the narrow inaka roads. This must be the place, I thought. As I stepped inside the little theater, I saw that it was packed to the gills. The audience, entirely comprised of (mostly older) locals, sat on rows of floor cushions facing the stage, all the way to the back of room, where latecomers stood. On stage young boys costumed

as exquisite cranes whirled like dervishes, dipped and bowed and fluttered their wings around a beautiful maiden (also a young boy) dressed in brilliant red. Whispers began to circulate as the locals realized a wild gaijin had appeared in their midst, and I was excitedly ushered into a better seat toward the front.

For the next several hours I was treated to a dazzle of color and sound. A variety of self-contained scenes, and a few longer plays, were presented, broken up by intermissions where the little old ladies in the audience chatted happily with their neighbors and whipped snacks out of their bags to share with one another. Some of the scenes were dance performances with little discernible plot. Others appeared to be family dramas or historical epics, where I could mostly figure out the characters and their relationships from their interactions and costuming. Even without understanding every element of what I had just seen, I left the theater at the end of the night enchanted, and feeling very lucky to have been invited into such a traditional space in my inaka community.

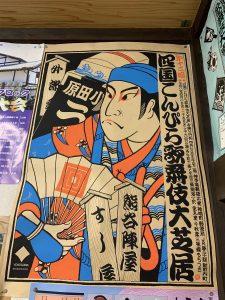

Almost a year later I returned with my friend and translator, Toshie Ogura, to interview one of the kabuki actors and sit in on a rehearsal for the upcoming kabuki festival. This time we entered from backstage, and found images of painted kabuki actors peering down from the walls. Every surface seemed to be covered with old posters, yellowing newspaper clippings, and playbills of past shows. Backstage was also surprisingly full of women, working on props, costumes, and equipment. On the stage itself, rehearsal was already in progress. Actors—and surprise again, a few actresses!—mostly in street clothes, rehearsed their blocking.

We were introduced to our contact, Taiki Yokobayashi, a mild-mannered young teacher by day and master kabuki actor by night, who showed us around the theater before settling into an interview. In particular, he directed us to a wall of photographs, rows upon rows of pictures of groups of children and teens in full costume and makeup, posing on stage. “This is me!” He said, pointing to one young boy, then to another, “and that is my friend, there!” He gestured to a grown man practicing on stage, and then back to the photographs, “That’s him many years ago, and this one’s his father!” And on and on, the faces go back for generations.

We were introduced to our contact, Taiki Yokobayashi, a mild-mannered young teacher by day and master kabuki actor by night, who showed us around the theater before settling into an interview. In particular, he directed us to a wall of photographs, rows upon rows of pictures of groups of children and teens in full costume and makeup, posing on stage. “This is me!” He said, pointing to one young boy, then to another, “and that is my friend, there!” He gestured to a grown man practicing on stage, and then back to the photographs, “That’s him many years ago, and this one’s his father!” And on and on, the faces go back for generations.

Note: All interview responses were originally in Japanese. They have been translated into English by Toshie Ogura and transcribed and edited by Rachel Fagundes.

Rachel: Thank you so much for letting us interview you! Please tell us about this kabuki troupe.

Yokobayashi: This group is the Awai Kasuga Kabuki Preservation Association. This building is 20 years old. Before that, this kabuki group used to act on the outside stage of the Kasuga shrine for roughly 30 years. So they have roughly 50 years as a formal group. Before that, there was no fixed group in this area, but the indigenous people used to perform kabuki to worship the gods in autumn and to celebrate the harvest.

We are quite famous in Japan, in Okayama. It’s because the young people are disappearing from the countryside. They want to hunt for their jobs in the city. The countryside people want to revitalize the villages, so the city and the countryside people focus on this kabuki group.

Rachel: Your kabuki festival is in October, right? What about the rest of the year?

Yokobayashi: From July we begin practicing. Each person has their work. There’s no admission fee so it’s all for free, all volunteers.

There are three places for us to play kabuki every year. This is our main location. We also play in Nagi. There are two big kabuki groups in this area. Our group, and the Nagi group. We have our festival here, at this temple, and two weeks later the Nagi Group has their festival. The Nagi Group always asks us to perform one play at their festival with them. This year I am playing Hatsugiku at both festivals.

Have you ever heard of Konpira Kabuki,* in Shikoku? We also perform in the “Sanuki Kabuki Festival” there in Kagawa Prefecture every October.

*Konpira Grand Theatre, also known as “Kanamaru-za” is the oldest kabuki theater in Japan still standing. It was built in the 1830s and recently restored to its original Edo period appearance.

Rachel: What types of stories were performed to worship the gods?

Yokobayashi: We have all the scripts for all the titles this group plays, have ever played ever. There are 16. We pick four of them to perform every year, plus the crane dance, which we do every year at the start.

However, we don’t write a special story to worship gods. Instead we perform with worshiping thoughts and feelings in our minds.

Rachel: How long have you been a kabuki actor?

Yokobayashi: For 21 years. I started when I was maybe turning 6 or 7.

Rachel: Do you come from a kabuki actor family? How long has your family been performing kabuki?

Rachel: Do you come from a kabuki actor family? How long has your family been performing kabuki?

Yokobayashi: My great grandfather, grandfather, father, and I have all been playing kabuki together as a family—so four generations. A few families in our theater troupe are like that, but that’s kind of rare.

Rachel: What was it like learning kabuki from your father?

Yokobayashi: Autumn is kabuki festival season for me. It’s a matter of fact. It’s natural for me. From my childhood I have admired kabuki, thinking, “Oh, it’s so cool!” So I wanted to do that. My father has never said “Do kabuki!” or “You have to do this!” but since I admired the kabuki players, it was natural for me.

Rachel: Were you able to see your grandfather perform also, when you were a child?

Yokobayashi: I don’t remember actually. My grandfather died young, but there are many pictures that I can see. And I’ve seen videos of him performing.

Rachel: Usually kabuki actors are all men, playing both the male and female roles. But some modern kabuki troupes allow women. There are women in this group, right?

Yokobayashi: There are professional Edo kabuki groups or Edo families, so they are kind of real, high-class professional kabuki players. When it comes to the professional kabuki players, women are totally not allowed to play on the stage. However, when it comes to our local kabuki troupe, Awai Kabuki, anyone is welcome. This group especially is very inclusive, regardless of ages, sexes, whether you are from a kabuki family or not.

Most of our actors are people who are connected to the Awai area in some way. They aren’t all from kabuki families. Some have not played kabuki before, but I invited them in so that we could perform kabuki together and they said “why not!” As long as they come to practice anyone is welcome.

A couple of years ago foreign people used to practice for this kabuki play for a couple of years in a row. They used to act on the stage, not in leading roles, but it was very impressive.

Rachel: You have sisters also, right? Are they involved?

Yokobayashi: They used to act on the stage!

He proudly directs us back to the pictures on the wall, where his sisters can be found among the others.

Three brothers and sisters on the stage when we were children. After they graduated from junior high, they stopped acting, but I decided not to stop acting. My sisters got married and they live in Tsuyama, but they come back to this kabuki in the autumn festival. My oldest sister has two children, the oldest is turning 2 so we are discussing him playing on the stage. So that’s how our family is going to be. With my friend’s children, it’s the same. We are chatting happily “maybe next year, or maybe next-next year, your children are going to join our kabuki!

Yokobayashi explains the plot of Revenge of Hideyoshi Part 10—Amagasaki in a Hidden Place, a tragedy about the doomed young lovers: Jujiro, who must go off to battle, and Hatsugiku, his devoted fiance. While he is getting into the somewhat complicated historical circumstances that led to this scenario, our interview is interrupted by his own father who, grinning, shows us a picture from last year’s performance.

Yokobayashi explains the plot of Revenge of Hideyoshi Part 10—Amagasaki in a Hidden Place, a tragedy about the doomed young lovers: Jujiro, who must go off to battle, and Hatsugiku, his devoted fiance. While he is getting into the somewhat complicated historical circumstances that led to this scenario, our interview is interrupted by his own father who, grinning, shows us a picture from last year’s performance.

In it, Yokobayashi stands in full costume as the noble young warrior Jujiro, and his father poses delicately on his arm as Jujiro’s 16 year old fiance.

Both laugh.

“Everyone was busy!” Yokobayashi explains, “A girl my age was supposed to be Hatsugiku, my fiance, but everybody got busy, so my father had to stand in!”

Rachel: Can you tell me about the kabuki makeup? Does each actor apply their own?

Yokobayashi: We don’t put on makeup by ourselves. There are professional makeup artists for kabuki who are called kaoshi.

Rachel: Does that run in families also?

Yokobayashi: It’s not a family-style. If you really want to be a makeup artist for kabuki, you have to ask the master for training. To be an apprentice.

Rachel: So how many makeup artists work with this group?

Yokobayashi: This group doesn’t have any professional kabuki makeup artists which are exclusive to this Awai kabuki group. So we always ask the Nagi Kabuki group to borrow their makeup artists. Maybe three or four makeup artists.

Rachel: What is the makeup made of?

Yokobayashi: Horse fat. Horse oil.

Rachel: What—Wait, what?

Yokobayashi: Horse oil.

Rachel: So, is this oil you put on the horse, or is this oil made from the horse’s body?

Yokobayashi: It’s kind of a solid oil. It’s not liquid. So you take the oil and get it melted on your palms and then spread it on our faces and then put white powder on it. It’s kind of a face painting. Body paint. So with the horse oil, it will be easier to spread the face painting better, smoother.

It’s really really hot on stage because of the light and we have to wear kimono and heavy costumes, but the makeup doesn’t move or sweat off. Afterwards, it’s really difficult for us to remove the makeup because of the horse oil.

Rachel: Does it smell?

Yokobayashi: A little. It’s kind of a fat oil.

Rachel: So how does the makeup define the different characters?

Yokobayashi: Ah yeah, it depends on the character, how to do the makeup is different. Totally different. Have you heard of Kuge? Kuge are like, high society people. So the eyebrows should be like dots. Round dots.

The makeup of samurai should be straight. Straight lines. Straight and thick. When it comes to the strong characters, the makeup should be like kumadori**.

There are books on how to make up each character. So when it comes to Hatsugiku, she should be like this. So the makeup artist should always see the textbook of each role, and they makeup according to the textbook.

**stage makeup worn by kabuki actors in the aragoto acting style. Kumadori makeup is highly stylized and characterized by bold stripes and symmetrical patterns on the face.

Rachel: So, her character type will appear the same every time.

Yokobayashi: Yeah. And so when it comes to the veteran makeup artist, he doesn’t have to see the textbook because he knows everything. That kind of craftsmanship.

Rachel: Tell me about the character archetypes.

Yokobayashi: When it comes to kabuki, there is not purely good heroes or purely villainous characters. For example, even though he is an asshole in this play, there is a good point to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The characters are complicated.

Rachel: I know that the language of kabuki is very ancient. It can be difficult for modern Japanese people to understand. So, as an actor how do you communicate to the audience?

Yokobayashi: Actually I don’t understand the lines myself at first. When I first get the script for a new play, I don’t understand what kind of lines they are and what they are saying. I have to research the meaning, or ask someone, until I understand. And after I understand the lines I try to express it using emphasis in my voice, or in my body language and behavior, or using mie.

Mie are theatrical poses struck at the height of a dramatic moment to emphasize its importance in the scene. They are an important element of the aragoto style of kabuki acting.

The hyoshigi, wooden block instruments, are key to marking these moments. Yokobayashi explains, “When it comes to doing mie, the wooden instruments should create a beat that becomes more intense, to a crescendo. Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton!”

The hyoshigi, wooden block instruments, are key to marking these moments. Yokobayashi explains, “When it comes to doing mie, the wooden instruments should create a beat that becomes more intense, to a crescendo. Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton! Ton!”

We practice striking the wooden instruments in a fast rhythm. He strikes a pose as each strike rings out, freezing his face in a dramatic expression, moving slightly in between the beats. It’s almost like vogueing. The strikes become more rapid and intense as the moment escalates towards its emotional climax.

Rachel: Can you tell us about the stage?

Yokobayashi: This is a rotating stage. During a performance, backstage staff put a peg into this hole, from the top, and they rotate the stage. This changes the set, so there are scene changes.

Rachel: Is this a common feature in many kabuki theaters?

Yokobayashi: Yes, it’s often.

Rachel: Are there any special effects, or tricks?

Yokobayashi: The lights are so hot for the actors, the lights are designed not to shine on the audience but to be bright on the actors, to focus on their faces. So the lights are a kind of special effect. At this theater the performances are at night.

Rachel: Can you tell me about the musicians who perform with the kabuki plays?

Yokobayashi: There is a narrator, a shamisen player, a hyoshigi (wooden block) player, so there are three players with kabuki. For each title, the lineup can be different. Sometimes there are three shamisen players for one title, like a high tone shamisen, a low tone shamisen, and a normal shamisen. There should always be one narrator and one wooden block player, but there could be one, two, or three shamisen players depending on the play.

When it comes to the wooden block player, there is no fixed musician for that. For example, if I do not have a role to play in a particular title, I can play the wooden blocks. But the narrator and the shamisen players are fixed roles, they are not actors. We borrow them from Nagi.

Rachel: It sounds like all the local kabuki groups help each other.

Yokobayashi: Our group cannot live without the Nagi kabuki group. We borrow many costumes from them also. So indigenous kabuki groups help each other to pass on their traditions.

Rachel: What do you want foreigners to understand about kabuki?

Yokobayashi: Kabuki is really unique to Japan, so I want foreign people to understand the whole uniqueness, so for example, the atmosphere itself, the story itself, is really Japanese-like. I want foreign people to experience authentic Japan.

Maybe foreign people won’t understand the whole story completely, but if they think ‘this part was really impressive’ or ‘I felt a really moved by their acting’—if they think so or they feel so, then we will be very happy.

Taiki Yokobayashi is a junior high PE, crafts, and computer science teacher. His motto is “Try anything! Experience counts.” He loves kabuki, has been performing since he was 7, and is the fourth generation in his family to be a kabuki actor. He’d like as many people as possible to learn about kabuki.

Toshie Ogura is a Japanese English teacher. She treasures her family, friends, and students, and loves to travel around the world. She also loves Japanese culture and studies tea ceremonies, calligraphy, kimono culture, Buddhism, and Japanese cooking. She enjoyed learning more about kabuki as well!

Rachel Fagundes is a third year ALT in Okayama Prefecture and the Entertainment editor of CONNECT. She previously worked as the associate editor of Tachyon Publications, and once taught a Lit class at UCSC on ethics and social justice in the Harry Potter novels. She likes science fiction, fantasy, the Italian Renaissance, and Japanese festivals. She will steal your cat.