This article originally featured in the December 2019 issue of Connect.

Paige Adrian (Gunma)

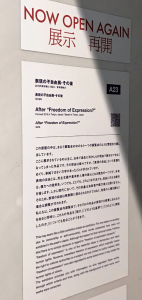

The Aichi Triennale, one of the largest art festivals in Japan with an average attendance of around 600,000 people, completed a semi-successful 75-day run in October (1). While the festival curated an impressive selection of art, it was plagued with controversy after Triennale staff decided to censor an exhibit titled After “Freedom of Expression?”. This exhibit contained the work Statue of a Girl of Peace by Korean artists Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung. The statue is a representation of comfort women: the name for Korean women who were forced into sexual servitude during World War II.

Following the exhibit’s closure, the festival faced repercussions from its artists, the government, and the media. But large art festivals, often organized as biennial or triennial events, are no stranger to scrutiny. They happen all over the world and attract an international audience, with the Aichi Triennale boasting over one hundred different artists and groups from numerous countries. Why one sculpture caused such an intense reaction reveals a lot about Japan’s weaknesses. It exists in a strange parallel to many of the other thought-provoking works at the Triennale, which questioned Japanese culture and history but did not receive the same attention.

People come to art festivals to see something outside the norm. Viewers want to be challenged and shown new perspectives. Larger events like the Triennale are the perfect place for those interested in exploring the many forms that contemporary art can take—there’s something for everyone. The variety of art on display at the Aichi Triennale was incredible, from large-scale installations like James Bridle’s Drone Shadow, a giant painted drone silhouette, to subtle works that almost blended into the environment, like Barteremi Togo’s garbage bags emblazoned with African flags, titled Africa: Western Trash.

Art festivals often highlight art that connects to the local place and culture, meaning that the hosting location can experience a reawakening of sorts. The Aichi Triennale placed many of their artists in the older Endoji neighbourhood, featuring works in traditional houses and lining the weathered shopping street with Ayşe Erkmen’s graceful coral ropes. Although these projects interact with the past and local places in benign ways, that doesn’t preclude works that may question or reveal negative histories.

The Aichi Triennale featured many works offering commentary on social topics. My favourite exhibit might be the work of artist duo Kyun-Chome, who filmed intimate exchanges between parents and their transgender children. In one video, a transgender man held a calligraphy brush together with his mother. In unison, they wrote his original name in black ink, and then wrote his chosen name over it in red. Throughout the process, their conversation revealed a bittersweet intersection between gender identities and generational differences, and how that intermixes with Japanese culture. Another enlightening work was The Clothesline by Mónica Mayer, a project started in 1978 which asks participants to write their experiences of sexual violence or misogyny on a slip of paper. Women looked over the papers knowingly while one man read wide-eyed, seemingly shocked. For a work that’s over forty years old, it’s sad that it remains so necessary. These are just two works of many that offered criticism and insight into diverse topics like gender, privacy, eugenics, war, colonization, urbanization, and immigration—all difficult issues to which Japan is no stranger.

One work I had a weird experience with was a performance piece called The Romeos. Posters placed throughout the venues warned that you may find yourself speaking to an “attractive young man” who started the conversation under false pretenses. The posters said he may even attempt to move beyond conversation and suggested a love affair as a potential outcome. The work claimed to take inspiration from a Cold War spy strategy, but to me it was oddly similar to the practice of “pick-up artistry,” an exploitative internet-based culture that’s risen in popularity in recent years. I was standing inside a room crying, thanks to artist Tania Bruguera’s infusion of menthol in the air. It was intended to evoke tears over a number representing migrant deaths. A man came up to me and noted that the menthol seemed to be working. I laughed and we walked out, continuing to the next artwork and discussing our worldly experiences. It wasn’t until halfway through the conversation that I accused him, shocked: “You’re a Romeo!” He chuckled and admitted that he was. His friend, the creator of the work, had asked him to be one of her Romeos for the Triennale. “I’m usually quite shy,” he mused. Despite our pleasant chat I didn’t feel swayed on the work’s unconvincing premise. But regardless of my personal dislike for The Romeos, I would never expect it to be removed or shut down. In fact, it was one of the pieces that I thought about the most during my visit, and the value of that can’t be denied.

Those who censored Statue of a Girl of Peace could not see value in pieces that prompt discomfort. The visual characteristics of the piece are not particularly inflammatory. A Korean girl sits on a chair with her fists clenched, a bird on her shoulder. Of course, its implied meaning is much more evocative in light of its further context—another version of the statue sits in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul, which the Japanese government has heavily protested. Triennale artistic director Daisuke Tsuda, once a journalist, had organized After “Freedom of Expression?” with the express purpose of showcasing works which had been censored in Japan at some point, making the closing of the exhibit all the more absurd. To accompany each piece, Tsuda wrote about the work’s history and why it had been censored (2). This educational intent apparently wasn’t good enough as Triennale staff faced angry phone calls, twitter rants, and—only in Japan—a threatening fax (3). The mayor of Nagoya was one of the exhibit’s most outspoken opponents, and The Agency for Cultural Affairs has refused to provide promised funding to this years’ festival (4). Many Triennale artists revoked the display of their work in response to the censorship, though the original exhibit and its artworks were eventually reopened for the festival’s final weekend. As is usually the case with censored works, the restored exhibit drew so much attention that admission had to be designated through a lottery system, and the crowds of people made it hard to even walk past for a possible glimpse.

Although the closure of Statue of a Girl of Peace is disappointing, the fact that the sculpture can elicit a reaction of this magnitude suggests an important purpose of contemporary art. Additionally, the support from other artists, as well as the public who spoke of and saw the exhibit, serves to shine a greater light on the statue and the history we need to remember. I hope this incident provokes further interest and meaningful engagement with art in Japan. If you’re interested in experiencing a Japanese art festival in the coming year, these are some options you can look forward to:

1 ROPPONGI ART NIGHT

May 30 to May 31

2 YOKOHAMA TRIENNALE

July 3 to October 31

3 OKU NOTO TRINNALE

September 5 to October 25

4 YAMAGATA BIENNALE

September 1 to 24

5 BIWAKO BIENNALE

September 12 to November 24

6 TOKYO BIENNALE

October 12 to November 24

Referenced Works and Further Reading

1) Aichi Triennale – Official Website

2) Outrage over Aichi Triennale exhibition ignites debate over freedom of expression in art by Philip Brasor

3) The Threat to Freedom of Expression in Japan by Andrew Maerkle

4) Aichi Triennale exhibition may trigger legal battle by Maiko Eiraku

Paige Adrian is a second-year Gunma ALT hailing from Saskatoon, Canada. She dabbles in writing, photography, and illustration when she’s not on a road trip, lurking at a conbini, or being a pop culture snob. You can see more of her work at paigeadrian.ca.