This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of CONNECT.

Sophie McCarthy (Hyogo)

Throughout many centuries and various cultures, flowers have long been symbols of grace and reverence; Japan is no exception. Ikebana (生け花, literally “giving flowers life”) is a practice that has perfectly honed how to accentuate the delicate and mystical beauty of flowers. During my time on the JET Program in my school club, I received an inside look into this ancient art that is still widely practiced across Japan today.

Ikebana as an art form first began more than 500 years ago during the Muromachi period (1392-1573). Originally called tatebana (立花)], these flower arrangements were presented as religious offerings to Shinto gods and deities. The tatebana style was characterized by flowers standing upright and tall, as if reaching to the gods themselves. Later in the Momoyama period (1560-1600), the offerings became more artistic, complex, and elaborate. Additionally, they gradually decorated not only religious altars, but also the homes of nobility and samurai.

As with many other parts of Japan, during the Meiji period (1868-1912), the art and rules of ikebana changed dramatically. This time saw the development of seika (生花) style, which was made specifically for the tokonoma alcove in Japanese style rooms. Seika is a triangular-looking style, with three main lines representing heaven, human, and earth—all together representing the universe. Especially in the past, when the tokonoma alcove was considered a sacred spot, the positioning of the flowers and the use of empty space were vitally important to the seika style.

In part due to the influence of the West, ikebana arrangements began to be placed in non-sacred, open places during the Meiji period as well. This created a need for more dimensional styles. The moribana (盛り花) style takes advantage of 360-degree viewing and focuses more heavily on the materials used in the arrangement themselves. As the name suggests, materials are piled on and rebel against the traditional, structural styles.

In part due to the influence of the West, ikebana arrangements began to be placed in non-sacred, open places during the Meiji period as well. This created a need for more dimensional styles. The moribana (盛り花) style takes advantage of 360-degree viewing and focuses more heavily on the materials used in the arrangement themselves. As the name suggests, materials are piled on and rebel against the traditional, structural styles.

Today, countless other forms and variations of ikebana exist. The socio-economic barriers that allowed only the cleric, aristocrat, warrior, and bourgeoisie to enjoy it have fallen, and now anyone from any background can appreciate and try out this popular cultural tradition. There are one-time, weekly, or monthly classes available everywhere in Japan for learning ikebana (often at local community centers), and annual exhibits are held all across Japan where ikebana professionals show off their best work. I highly recommend this one famous ikebana exhibition at the Daimaru in Kobe.

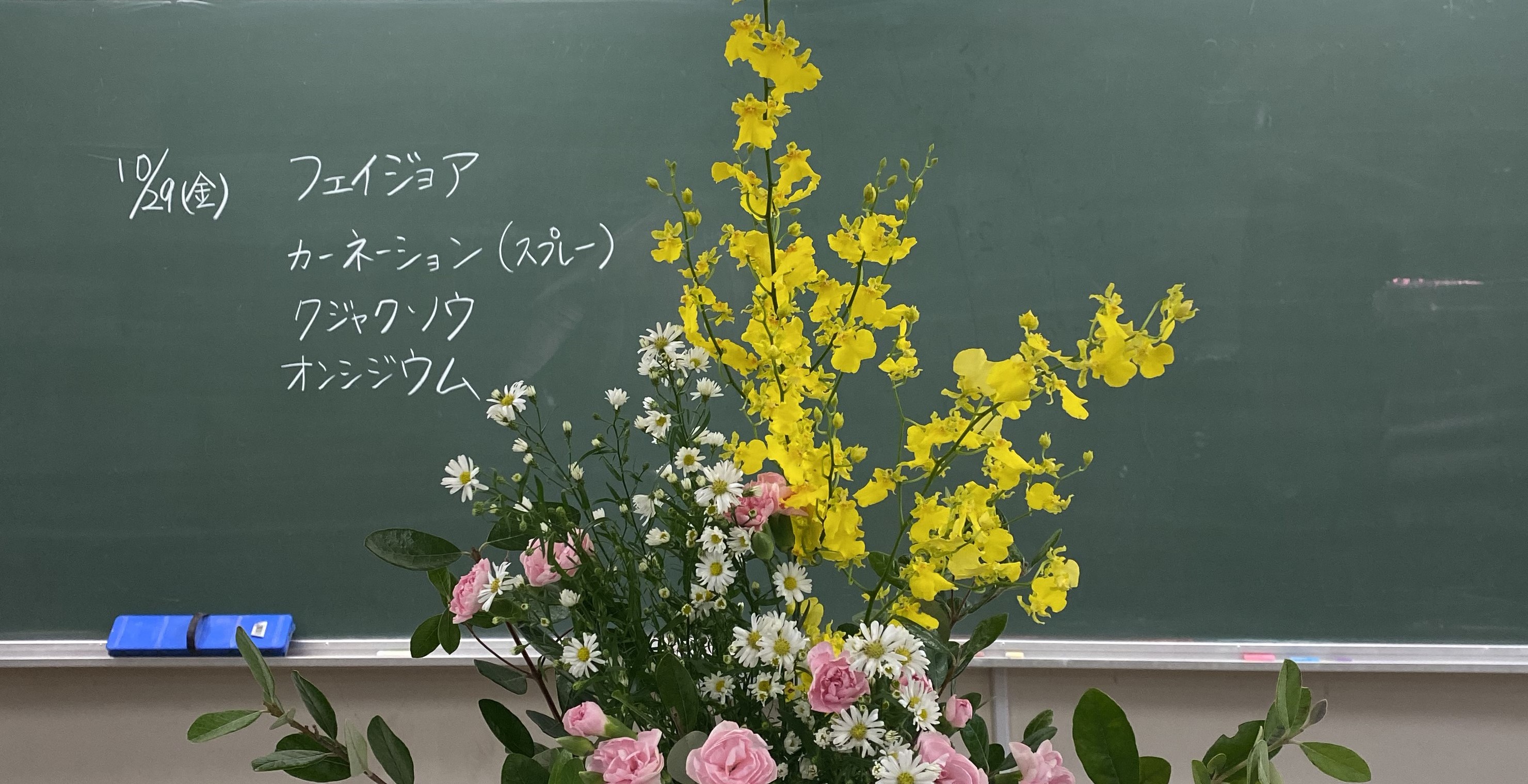

In many Japanese high schools, the ancient practice is kept alive and well in the form of afterschool club activities. During my time on the JET Program, I took part in monthly ikebana meetings with my students. Flowers in tow, a certified ikebana teacher would come to teach us not only about the act of flower arranging, but the world of flowers too. We learned the Japanese (and English) names of flowers, where the species originate, the environments they grow naturally in, and the seasons when they bloom. One of the most interesting species I learned about was nandina (南天) or “Heavenly Bamboo.” Despite its name, it is not actually a bamboo but an evergreen shrub that is native to eastern Asia, from Japan all the way to the Himalayas. Ironically, the berries that grow on the plant in winter are also toxic to animals. The most captivating information I learned, however, was when I realized that this plant had been growing in my own garden for the past few years and until that moment, I never recognized what it was.

Japan is a country that has always staunchly embraced seasonal activities and traditions, especially in terms of nature. Established all the way back in the Heian period (794-1185), viewing plants and appreciating flowers was a Japanese aristocratic pastime. Whether hanami (花見, cherry blossom viewing) in the spring or koyo (紅葉, autumn leaves viewing) in the fall, I greatly admire how in tune the Japanese people are with the changes in nature around them. This appreciation of the seasons extends into the art of ikebana as well. In fall and winter, we would incorporate foliage from those seasons such as chrysanthemums or plum blossoms in our designs. We would utilize flowers such as sunflowers, hydrangeas, or sword-lilies (gladiolus) in the warmer months. I was always impressed by the wide variety of flowers we used over the course of my four years in the club—by the care that was given into ensuring complimentary flowers were chosen for the arrangements.

Japan is a country that has always staunchly embraced seasonal activities and traditions, especially in terms of nature. Established all the way back in the Heian period (794-1185), viewing plants and appreciating flowers was a Japanese aristocratic pastime. Whether hanami (花見, cherry blossom viewing) in the spring or koyo (紅葉, autumn leaves viewing) in the fall, I greatly admire how in tune the Japanese people are with the changes in nature around them. This appreciation of the seasons extends into the art of ikebana as well. In fall and winter, we would incorporate foliage from those seasons such as chrysanthemums or plum blossoms in our designs. We would utilize flowers such as sunflowers, hydrangeas, or sword-lilies (gladiolus) in the warmer months. I was always impressed by the wide variety of flowers we used over the course of my four years in the club—by the care that was given into ensuring complimentary flowers were chosen for the arrangements.

While my time with JET and my ikebana club has ended, the fondness I have for this incredibly skilled art form is something I will carry with me for many years to come. Additionally, the knowledge the club bestowed on me about different plants and foliage is something I’m able to use walking outside in my everyday life. Before, I felt somewhat passive passing through nature, feeling like an outsider and not really paying much attention to it. Now, seeing flowers brings me so much joy, and knowing what they are and what they mean to the people here makes me feel like I’m a participant in nature and part of this world. This is, and will remain, one of my fondest memories on the JET Program.

“What is Japanese culture?” isn’t a question that has one simple answer. From anime to bullet trains and city pop music to shrines, all of it is Japanese culture, and every person identifies with different aspects of it. For me though, ikebana was one aspect of Japanese culture that connected to me the most. Ikebana has a rich and storied past with an intimate connection to the natural world.

Sophie McCarthy was a JET for four years (2018-2022) in Kobe, Hyogo, and now lives in Tokyo. In her free time, she enjoys reading classic literature, visiting coffee shops, and practicing film photography. Check out her photos on Instagram: @filmbysophie

Sources

The Essence of Ikebana by Saga Goryu Ikebana Headquarters

Moribana from Brittanica

Ikebana from JapanObjects

Image Credits

Sophie McCarthy