This article originally featured in the February 2022 issue of Connect.

Valerie Osborne (Fukuoka)

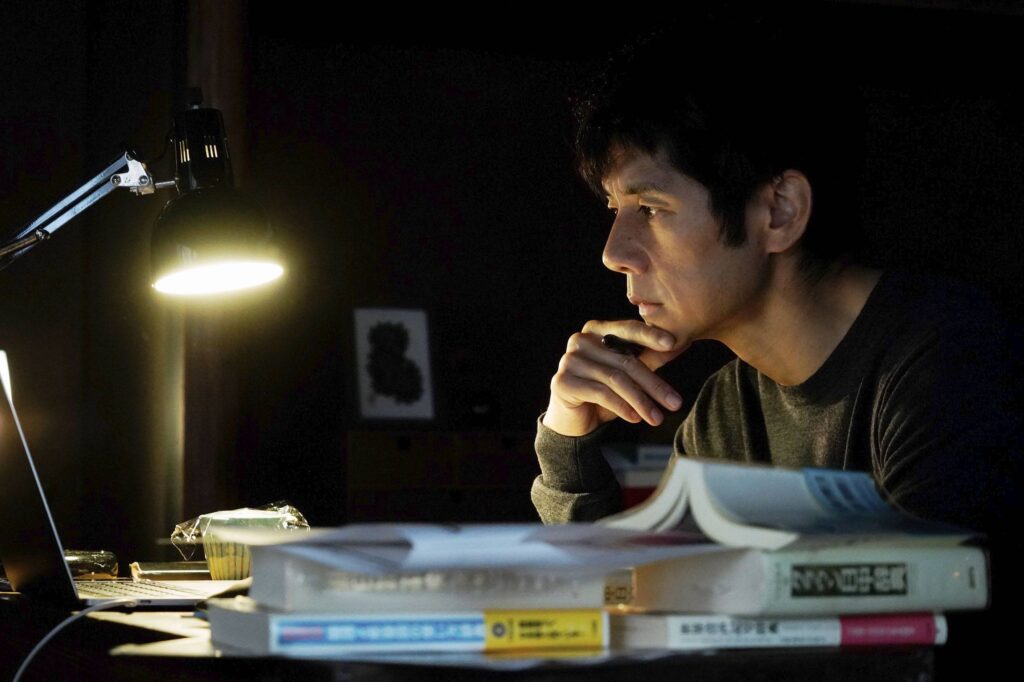

Winner of Best Picture from the National Society of Film Critics and the Golden Globe for Best Non-English Film, Japan’s 2022 Academy Award pick, Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s Drive My Car is a quiet, unassuming film that never drags despite clocking in at almost three hours. An expanded adaptation of Murakami Haruki’s short story of the same name, the film begins by introducing the audience to theater actor Kafuku Yusuke (Nishijima Hidetoshi) and his television writer wife, Oto (Kirishima Reika). Kafuku and Oto appear to share a close emotional and physical bond, a bond soon questioned when Kafuku discovers his wife has been having an affair with a much younger man. Choosing not to confront Oto, Kafuku finds himself questioning their relationship. These feelings are further confused when Oto unexpectedly passes away.

Winner of Best Picture from the National Society of Film Critics and the Golden Globe for Best Non-English Film, Japan’s 2022 Academy Award pick, Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s Drive My Car is a quiet, unassuming film that never drags despite clocking in at almost three hours. An expanded adaptation of Murakami Haruki’s short story of the same name, the film begins by introducing the audience to theater actor Kafuku Yusuke (Nishijima Hidetoshi) and his television writer wife, Oto (Kirishima Reika). Kafuku and Oto appear to share a close emotional and physical bond, a bond soon questioned when Kafuku discovers his wife has been having an affair with a much younger man. Choosing not to confront Oto, Kafuku finds himself questioning their relationship. These feelings are further confused when Oto unexpectedly passes away.

Two years later, Kafuku relocates to Hiroshima to serve as the resident director of a multi-lingual production of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, in which he casts his wife’s former lover and now disgraced television star, Takatsuki Koji (Okada Masaki), in the titular role. Against his will, Kafuku is assigned a personal driver as a requirement of his residency contract. The driver, Watari Misaki (Miura Toko), is a young woman dealing with her own traumatic past. Kafuku, Takatsuki, and Watari become the central figures of the film as it explores their relationships to each other and their shared grief.

The plot unravels in tandem with the production of Uncle Vanya, effectively reflecting Kafuku’s own feelings and inner conflicts. Similarly, a story told by Oto to Kafuku (and Takatsuki) is woven throughout the film, its climax eventually serving as a powerful, veiled confession from one of the film’s key players. Yet, despite this multi-layered storytelling, Drive My Car is minimal in both plot and style. Many of the film’s key scenes occur within the confines of the titular car, Kafuku’s red Saab. The film’s most impactful moment takes place in the car’s backseat: a conversation between Kafuku and Takatsuki. This confined space creates a shared intimacy between the audience and the characters. The camera lingers on the face of Takatsuki. As Takatsuki stares directly into the camera, it feels as if he’s speaking to the audience, forcing us to listen, no matter the discomfort.

There is a shocking act of violence that occurs towards the end of the film. A lesser film might have honed in on this act, yet here it occurs off screen. This is not a film about action but is squarely focused on the things that occur internally. It’s not so much the act of infidelity that bothers Kafuku, but the why…. What feelings and desires was Oto hiding from him? What truly bothers Kafuku is that there are sides of his wife that he can never know. So, too, Drive My Car is introspective, an exploration of the internal battles each character faces as they deal with their past traumas and try to understand their loved ones and themselves.

There is a shocking act of violence that occurs towards the end of the film. A lesser film might have honed in on this act, yet here it occurs off screen. This is not a film about action but is squarely focused on the things that occur internally. It’s not so much the act of infidelity that bothers Kafuku, but the why…. What feelings and desires was Oto hiding from him? What truly bothers Kafuku is that there are sides of his wife that he can never know. So, too, Drive My Car is introspective, an exploration of the internal battles each character faces as they deal with their past traumas and try to understand their loved ones and themselves.

Drive My Car is a somber film, but not a bleak one. The mutual-respect between Kafuku and Watari that blooms into a father-daughter like affection is sweet and comforting to watch. The final few scenes of the film are ones of welcome catharsis. Towards the end, the film briefly dips into melodrama. The film is being gentle with its characters here, allowing them the space to confront their emotions and move on from their grief. As Sonia affirms in the final monologue of Uncle Vanya, “What can we do? We must live our lives. Yes, we shall live, Uncle Vanya.”

Valerie is a 4th year ALT living in Fukuoka Prefecture. Originally from the US, she enjoys reading, traveling and karaoke.