This article originally featured in the January 2021 issue of Connect.

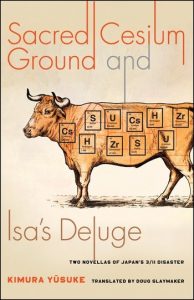

‘Sacred Cesium Ground’ by Kimura Yusuke

Alice French (Yamagata)

Political protests come in many forms. Boycotts, sit-ins, marches, flashmobs, the list goes on. For Yoshizawa Masami, of Namie Town, Fukushima Prefecture, political protest comes in the form of raising cows. He is the proprietor of Kibō no Bokujō (The Ranch of Hope), where he keeps around 300 cows, all of whom were abandoned by local farmers following the Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent nuclear disaster of Mar. 11, 2011 (otherwise known as 3/11). In the aftermath of the explosion of the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s (TEPCO) Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, the national government ordered all livestock in the surrounding area to be killed, as the animals were considered to be contaminated by the radioactive fallout. In defiance of this order, to this day, Yoshizawa continues to raise his cattle on the Ranch of Hope, situated just 14km from the power plant, in the hope that they will be a living reminder of the suffering that the rural Tōhoku region has experienced as a result of 3/11, and proof of what he considers to be the insufficiency of the government’s financial support for the farmers affected.

In 2014, author Kimura Yusuke visited Yoshizawa’s Ranch of Hope as a volunteer. His 2016 novella, ‘聖地Cs’ (‘Sacred Cesium Ground’), is a semi-fictional account of his time there. It follows the story of a young Tokyoite, Nishino, during her couple of days’ volunteering at a ranch called the “Fortress of Hope.” In between feeding the cows and shovelling a lot of what she refers to as “mudshit”, Nishino learns about the hardships that the people of Tōhoku have been subjected to at the hands of Japan’s central government from the ranch’s owner, Sendo. He asserts that Tōhoku residents have been treated like “disposable people,” their lives sacrificed to meet the needs of those living in the financial metropolis of Tōkyō (all of the power produced by Fukushima Daiichi before the disaster was fed directly back to Tōkyō). By the end of her volunteering stint, city girl Nishino, who was initially horrified by the cows on the “Fortress of Hope,” finds an affinity with the animals, and ends up reluctant to return to her monotonous Tōkyō lifestyle.

In 2014, author Kimura Yusuke visited Yoshizawa’s Ranch of Hope as a volunteer. His 2016 novella, ‘聖地Cs’ (‘Sacred Cesium Ground’), is a semi-fictional account of his time there. It follows the story of a young Tokyoite, Nishino, during her couple of days’ volunteering at a ranch called the “Fortress of Hope.” In between feeding the cows and shovelling a lot of what she refers to as “mudshit”, Nishino learns about the hardships that the people of Tōhoku have been subjected to at the hands of Japan’s central government from the ranch’s owner, Sendo. He asserts that Tōhoku residents have been treated like “disposable people,” their lives sacrificed to meet the needs of those living in the financial metropolis of Tōkyō (all of the power produced by Fukushima Daiichi before the disaster was fed directly back to Tōkyō). By the end of her volunteering stint, city girl Nishino, who was initially horrified by the cows on the “Fortress of Hope,” finds an affinity with the animals, and ends up reluctant to return to her monotonous Tōkyō lifestyle.

‘Sacred Cesium Ground’ is an excellent read, not only because it provides a rare and refreshing account of the 3/11 disaster as told by the farmers who were directly affected, which is invaluable within a narrative that is too often dominated by central government voices. The novella also offers a thought-provoking critique of the power structures in Japanese society. It is a story of dichotomies: collective versus individual, Tōkyō versus Tōhoku, animals versus humans, dirty versus clean. Within the confines of the “Fortress of Hope,” ordinary power balances are reversed. Tōhoku takes centre stage; animals’ needs are prioritised over humans’; the contaminated, radioactive grounds are regarded as “sacred.” Kimura thus suggests that 3/11, although a tragedy for the Tōhoku region, in fact, offers a promising opportunity to reevaluate the distribution of power in modern Japan. Although borne out of disaster, ‘Sacred Cesium Ground’ is, just like the ranch itself, ultimately a story of hope.

The English version of ‘聖地Cs,’ translated by Doug Slaymaker, is available on Amazon.

Alice French is a second-year CIR from Cambridge, England, based at the Prefectural Office in Yamagata. When she is not singing in the shower or taking pictures of sunsets for Instagram, she can be found hiking or skiing on one of Yamagata’s many mountains.