Bridging Past and Present Along the Kumano Kodō

This article originally featured in the September 2020 issue of Connect.

Sara Atwood (Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture)

In these past few months, with the coronavirus rampaging around the globe, travel seems like a faraway dream for most people. While we currently lack the opportunity to travel abroad, domestic travel is still a possibility if proper precautions are taken. Social distancing is completely feasible along the well-worn paths of the Kumano Kodō, where pilgrims have walked for over 1,000 years to purify the mind, body, and soul. This escape from the doldrums of quarantine and stress of the pandemic could be just what the doctor ordered.

What is the Kumano Kodō?

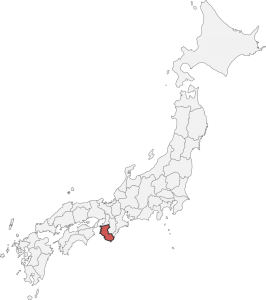

The Kumano Kodō is a series of pilgrimage routes located in the Kii Peninsula in western Japan. It is one of only two pilgrimage routes in the world that has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with the other being the Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James) in Spain. Multiple pilgrimage routes criss-cross the peninsula, though the most popular is the Nakahechi Route in Wakayama Prefecture, which was primarily used by the Imperial family on pilgrimages from Jonan-gu Shrine in Kyoto to the Kumano Sanzan— the three grand shrines of the region— from the 10th century onwards.

However, with the rise of the shogunate, Imperial pilgrimages came to an end around the 13th century. But pilgrimage culture in Japan, especially in the Kii Mountain Range, had already been well established. There was an overall decline in pilgrimages in the late 19th century, but the 1990s saw a resurgence in their popularity. After being recognised as a World Heritage Site in 2004, the area saw a dramatic increase in both domestic and international pilgrims.

It is one of only two pilgrimage routes in the world that has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site…

Gotta Collect ‘Em All— Ofuda, Goshuin, and Stamp Rallies

For centuries, Japanese pilgrims have purchased souvenirs from shrines and temples to bring back as mementos of their trip, symbols of their religious devotion, or talismans to protect themselves from various calamities. There are many types, but the two most common are ofuda and goshuin. Recently, stamp rallies have become another popular way of recording visits to famous places. It is possible to collect all of these along the Kumano Kodō, though I honestly didn’t know much about them before my trip.

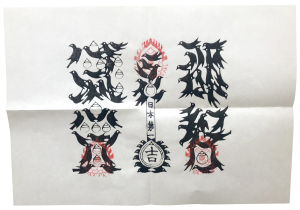

There are two kinds of ofuda talismans: the first is received from a Shinto shrine and bears the name of the shrine and/or its kami (god). People often keep them on their Shinto altars. The second protects against natural disasters, cures diseases, and more. You can get these from either Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples and place them in different areas of your home.

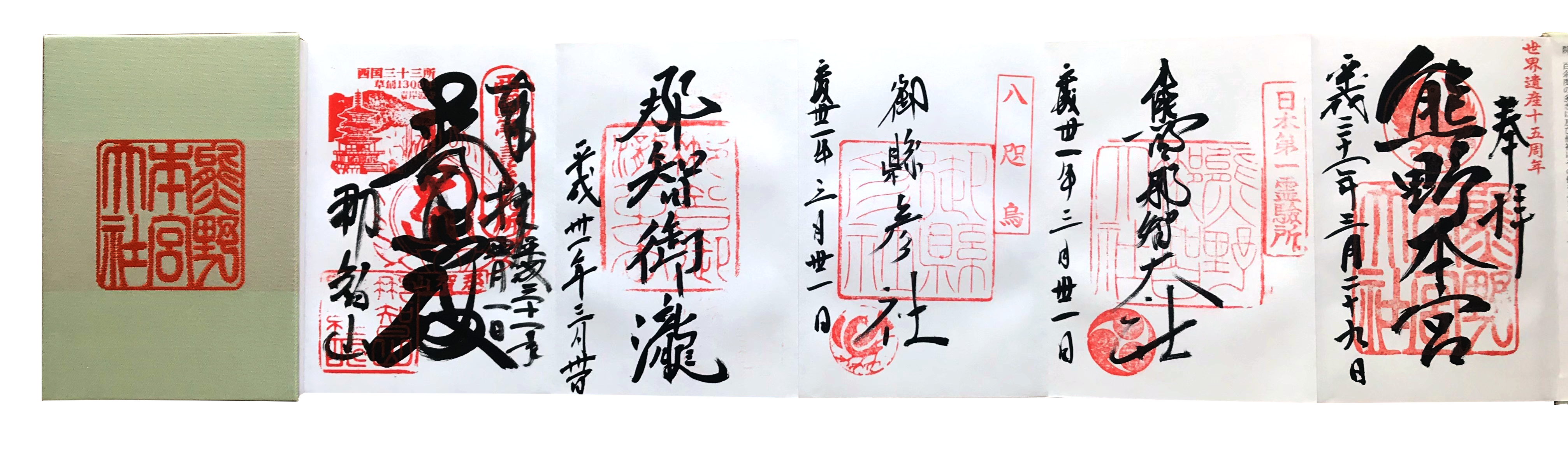

Goshuin are special, hand-written calligraphic seals collected by visitors to shrines and temples usually kept in a designated goshuinchō book. When visiting these sacred spaces, pilgrims would demonstrate their piety by giving offerings. In exchange, they would receive a goshuin as a physical record of having visited the temple or shrine. The practice of collecting goshuin has continued through the centuries and is now popular with visitors of all ages, religions, and ethnicities.

Goshuin are special, hand-written calligraphic seals collected by visitors to shrines and temples, usually kept in a designated goshuinchō book.

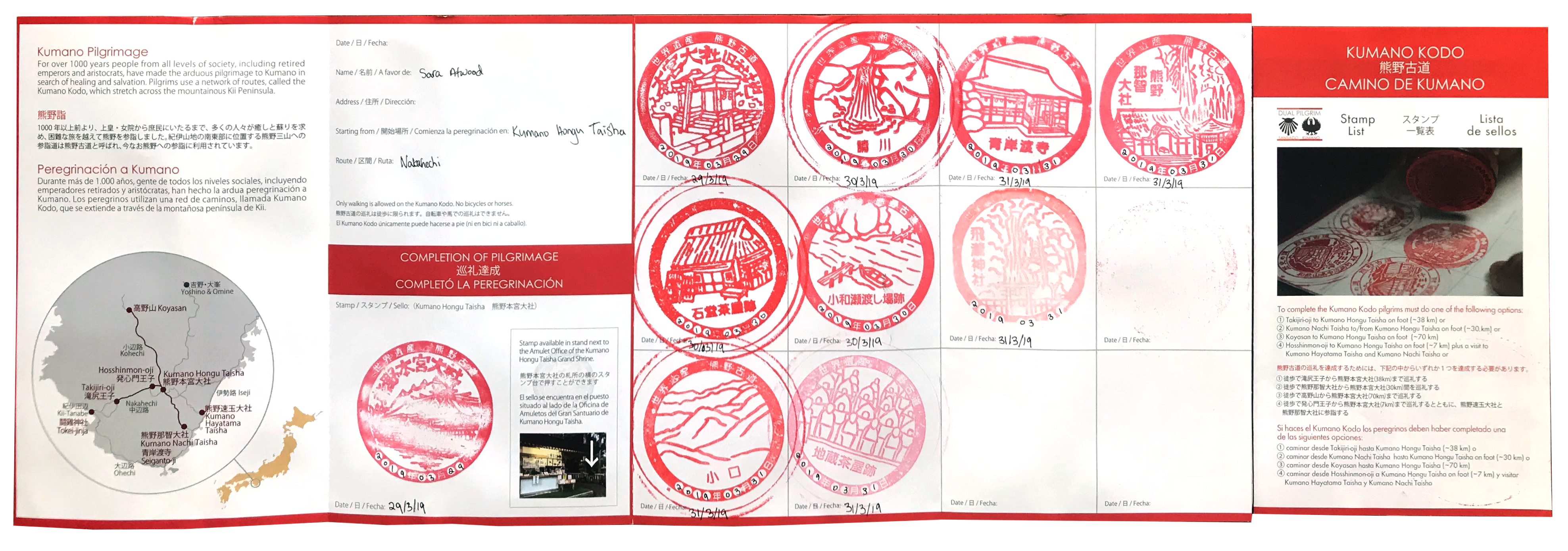

Modern-day stamp rallies are incredibly popular in Japan, with many being organised by railway companies, local government offices ,and major tourist sites, including temples and shrines. Visitors collect various stamps associated with an area or event, and if you collect them all, you can often win prizes. No one really knows when or how these rallies began, but they could be linked to collecting goshuin. While many religious centres have their own tourist stamps, it is incredibly important to put them in their own designated books. Goshuin are considered sacred, so if you fill your goshuinchō with any other stamps, monks and priests will often refuse to write any more goshuin in your book.

Traversing the Kumano Kodō’s Nakahechi Route

In November 2018, some friends invited me on a hike along the Nakahechi Route during the upcoming spring holidays, and I jumped at the opportunity. I was new to the JET Programme and had always planned on doing a pilgrimage in Japan, so this was the perfect chance to check something off the bucket list.

The planned trip was a three-day hike from Hongū Taisha to Nachi Taisha, which is roughly 30 kilometres across the Kii Mountain Range. On March 29, 2019, our group of five met up in Osaka and took the JR Kisei Line along the Wakayama coast to Kii-Tanabe Station. After having a quick lunch, we stopped by the local tourism office and picked up some stamp rally booklets before running to catch our bus.

About two and a half hours later, we reached Hongū Taisha. We climbed the steps to the shrine and paid our respects to the kami. I bought my first goshuinchō—a limited edition marking the 15th anniversary of Kumano Kodō becoming a World Heritage Site—and, while waiting for the shrine priestess to complete my goshuin, I got the first rally stamp in my booklet.

From there, we followed the riverbank, walking under the world’s largest torii at Oyunohara and up into the mountains. The first leg of the hike was a very short, yet steep, two kilometres, but luckily, we each grabbed a walking stick from the base of the trail before beginning the climb. We walked by statues of Jizō, a bodhisattva often associated with travellers, and through forests with trees stretching as far and as high as the eye could see, eventually arriving at our hostel in the small onsen town of Yunomine. After eating dinner and relaxing in the onsen, we crawled into bed.

Bright and early the following morning, we took a 30-minute bus ride to Ukegawa, where the hike began in earnest. We walked roughly 13 kilometres along winding trails through the mountain’s ancient forests, overlooking the incredible views of the valleys below, to the small town of Koguchi. It took about seven hours, including a lunch break and stamp collecting for our rally from the wooden stands at various landmarks along the way. Like the day before, upon reaching the hostel and relaxing in another onsen, we crashed early to prepare for the next day.

The third day was probably the most difficult. We were already shattered from our long hike the day before and had to psych ourselves up to trek another 14 kilometres to Nachi Taisha. This part of the hike contains the highest elevation point on the trail and some of the steepest, longest stairs I’ve ever seen in my life. It is gruelling, but there are also many historical places to enjoy along the way, like the ruins of Edo period teahouses and the Waroda-ishi. This sacred stone has three Sanskrit symbols carved into its face, each representing one of the main Kumano deities: Kannon (Bodhisattva of Mercy), Yakushi (Buddha of Medicine), and Amida (Buddha of Compassion). It is said that they meet here from time to time to relax and drink tea. We paused here to do the same, so I’d like to think we had one big tea party together.

When we finally began the descent to Nachi Taisha, we were rewarded with a breathtaking view of the ocean. Stumbling the rest of the way down the mountain, we arrived at our destination after about nine hours and just 15 minutes before the area closed for the evening. We quickly took a commemorative photo together and then rushed off to collect our remaining stamps and goshuin. After realising that it would be impossible to collect them all in such a short time, we decided to return the next morning instead.

This proved to be the best decision, as we could leisurely enjoy the scenery and atmosphere. We spent time taking in the views, snapping dozens of photos, buying omiyage, and collecting those final stamps. I also bought a special ofuda designed to bring good luck and ward off illness, which is now hanging in my genkan. When we finally wrapped up, we headed to Kii-Katsuura Station for the four-hour train ride back to Osaka, where we went our separate ways.

Even though the hike was long and difficult, the overwhelming sense of taking part in something spiritual made all the exertion worth it. Collecting ofuda, goshuin, and stamps transformed my ordinary hike into an enlightening contemporary pilgrimage, where I truly felt like an active participant in history. I hope that one day soon I will be able to walk the Camino de Santiago in Spain as well. If you collect the main rally stamps along both UNESCO World Heritage pilgrimage routes, you can receive a special certificate recognising your efforts and granting you the status of “Dual Pilgrim.”

Along the Kumano Kodō, your weary heart and soul are renewed by the sounds of chirping birds, rustling leaves, and flowing rivers. You may struggle sometimes along the way, but pilgrimages aren’t supposed to be easy. They’re about connecting to something larger than yourself and following in the footsteps of the centuries of pilgrims before you, while leaving footsteps of your own for others to one day follow.

Sara Atwood is a third-year ALT at a senior high school in Hyogo Prefecture. She has a MA in East Asian Art History from SOAS, University of London. She is especially interested in Japanese religious art history and women’s pilgrimage in the Edo Period. Her hobbies include playing video games, reading fantasy and science fiction novels, studying Japanese, and hiking. Instagram: @klfshepard