How I learned to embrace being multiracial

This article was originally published in the March 2023 issue of CONNECT.

Shou Seidai Yuan (Ehime)

The first thing I did after dumping my bags at the hotel for my Tokyo JET orientation was to go to the Lawson convenience store down the street. It was odd to suddenly be in a country I could only remember vaguely, having not been here for 15 years. Walking jetlagged down the street in Tokyo’s infamous humidity, I felt like I was having a lucid dream, syncing old sensory memories to what was in front of me. I realized I had never been in Japan in summer. Whenever I visited with my family as a kid, it was always spring or fall. My dad was born in Tokyo. He always said he missed certain things about this city, but he certainly made it known that he didn’t miss this swampy inferno every July.

The first thing I did after dumping my bags at the hotel for my Tokyo JET orientation was to go to the Lawson convenience store down the street. It was odd to suddenly be in a country I could only remember vaguely, having not been here for 15 years. Walking jetlagged down the street in Tokyo’s infamous humidity, I felt like I was having a lucid dream, syncing old sensory memories to what was in front of me. I realized I had never been in Japan in summer. Whenever I visited with my family as a kid, it was always spring or fall. My dad was born in Tokyo. He always said he missed certain things about this city, but he certainly made it known that he didn’t miss this swampy inferno every July.

I bought four rice balls there. No rice ball in the past five years I’ve been here has ever tasted better. Each was more delicious than the last, a stairway to nostalgic heaven, an instant return to childhood days.

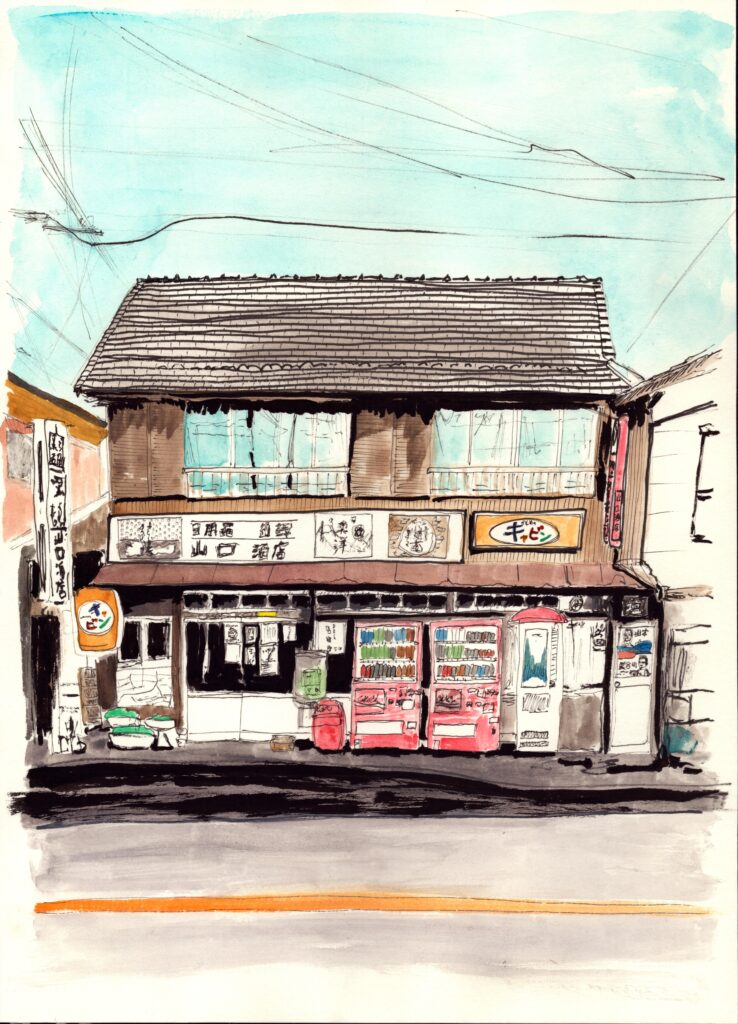

My grandma’s house in Kawasaki felt like a time capsule from another era, and I guess, in a way, it was. I remember the scarily steep staircase to the upstairs tatami room, the sliding doors, and the stone pathway out onto the street. I remember doing my American homework on a tiny dining table and dull incandescent light shining from the old fixture above. But more than anything else, I remember the smell of curry roux, slowly simmering in a dark corner of the old kitchen. Every time we visited, my grandma would make curry as the welcome meal. It was the earliest time I could remember food being an expression of love. I wish I had been old enough at the time to really understand this. I wish I had the words to be able to tell her what her curry and rice meant to me.

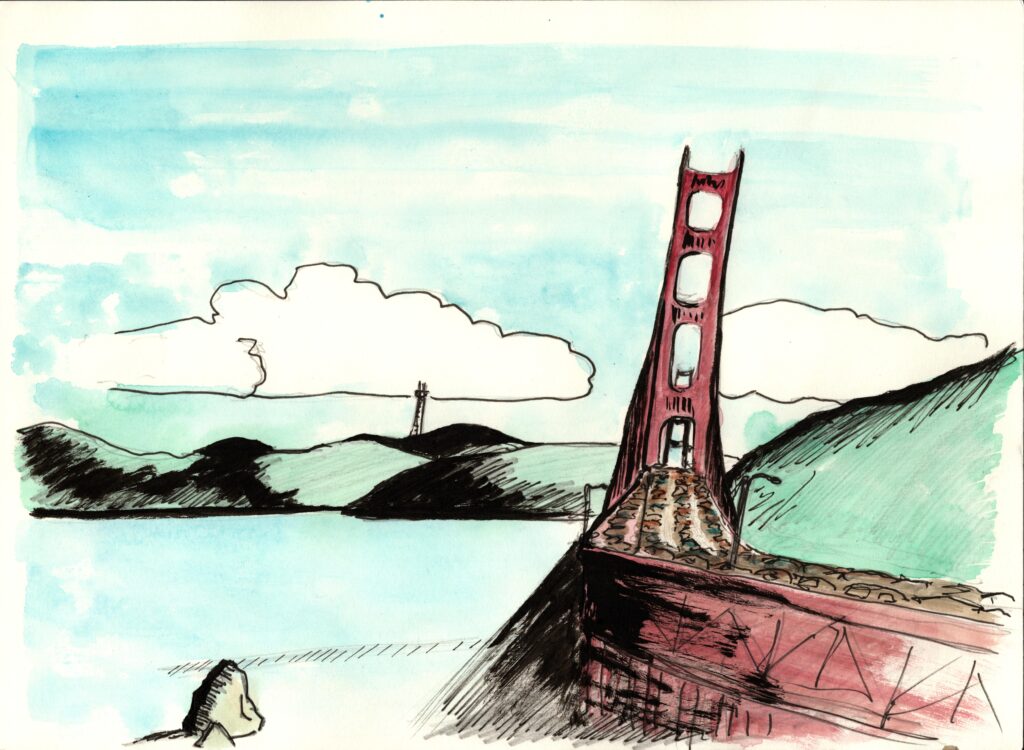

I’m old enough now to look back on it and realize things I couldn’t then. I was born in San Francisco, California in 1991 to a first generation immigrant father from Japan and a white midwestern migrant mother from Michigan. I spent most of my first 25 years of life there. It was a unique upbringing, a balance between my parents trying to be supportive but also holding certain expectations, my father especially. I don’t think I ever developed my Japanese language skills very well or learned to be culturally Japanese to the degree my father had hoped.

I’m old enough now to look back on it and realize things I couldn’t then. I was born in San Francisco, California in 1991 to a first generation immigrant father from Japan and a white midwestern migrant mother from Michigan. I spent most of my first 25 years of life there. It was a unique upbringing, a balance between my parents trying to be supportive but also holding certain expectations, my father especially. I don’t think I ever developed my Japanese language skills very well or learned to be culturally Japanese to the degree my father had hoped.

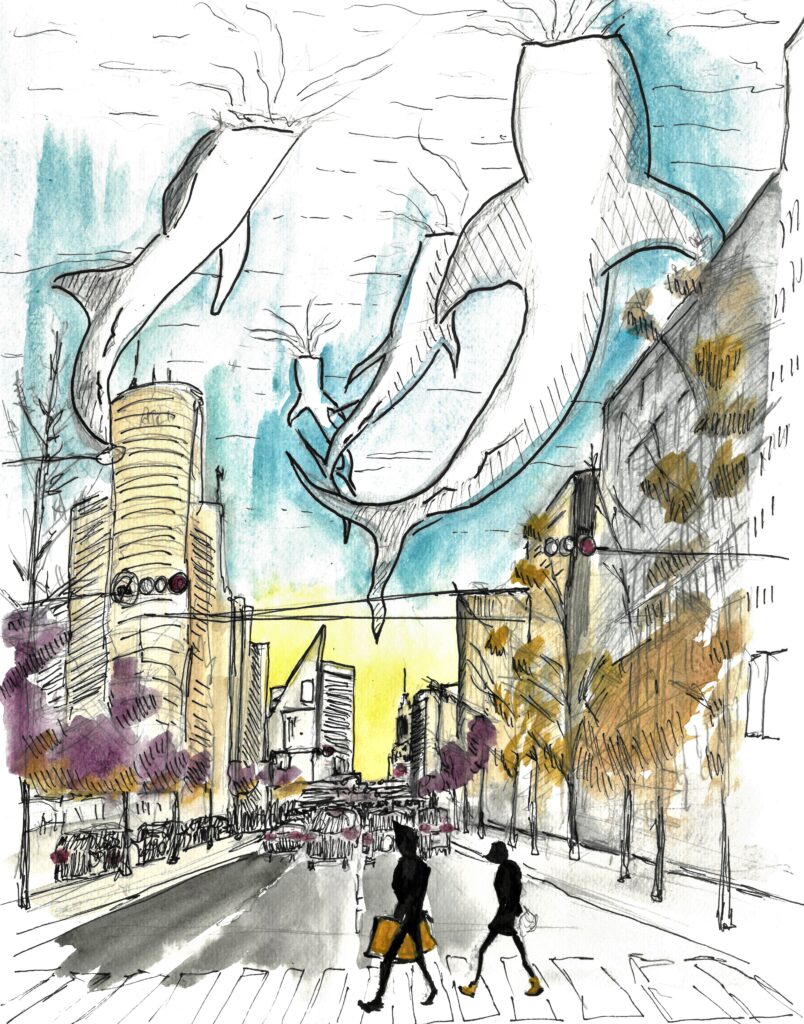

I had always wondered what it might have been like if my parents had settled in Japan instead, in some alternate universe where there was some version of me who was more Japanese than American. Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so conflicted back then if I had lived in Japan all along. Now I realize it doesn’t matter. That version of me, this version, and all the versions in between . . . we are not Japanese, nor are we American. It’s a gift now, not a curse—an ability to see things from multiple perspectives, the freedom from being expected or pressured into picking a side. I have the JET Program to partly thank for this.

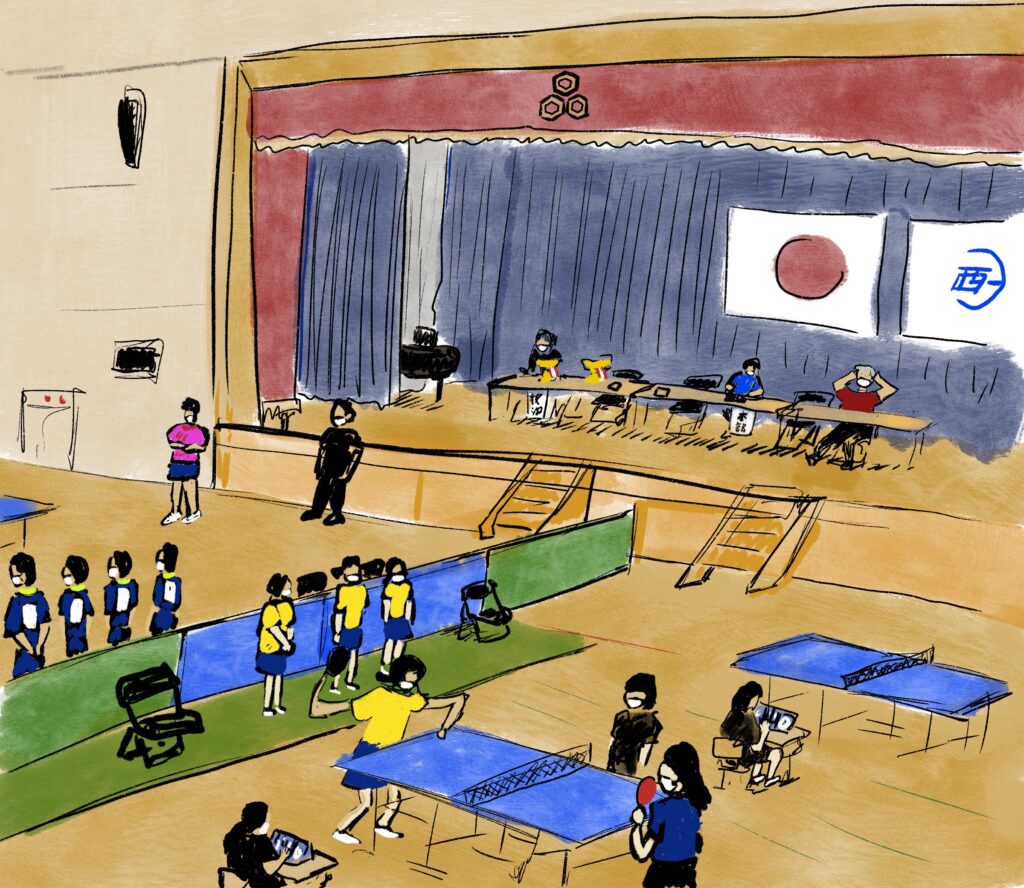

Being in Japan as part of the JET Program has given me a whole new outlook on my identity. Teaching my students every day at my assigned schools has been a rewarding challenge . . . and a glimpse into a life that I always wondered about. Through them, I’m able to look at what it could have been like to grow up in Japan, with all its experiences: the club practices and the drill tests, the long walk home in all seasons, the bugs.

Being in Japan as part of the JET Program has given me a whole new outlook on my identity. Teaching my students every day at my assigned schools has been a rewarding challenge . . . and a glimpse into a life that I always wondered about. Through them, I’m able to look at what it could have been like to grow up in Japan, with all its experiences: the club practices and the drill tests, the long walk home in all seasons, the bugs.

It is hard not to be impressed by my students and coworkers’ humor and adaptability to life’s daily absurdities: every stink bug that flies around the classroom causing a panic, every instance that one student in every class almost falls asleep, and every time a surprise costume is revealed at a festival. I admire the drama-less rhythm of the daily school routine, the way it allows kids the opportunity to experience different interests as part of the normal curriculum. These schools—and the Japanese education, more broadly—really value arts, crafts, and other creative fields as something everyone can attempt and enjoy through school-provided time and practice, not as something lesser or reserved for a gifted few. It’s that attitude towards the creative fields that I’m thankful my Japanese father imparted to me. As an artist now, I wish my American school and American education in general had promoted this more. As a JET, I’ve seen the results of this Japanese approach to creation through the creative projects of my students at a festival and in school exhibitions.

In a smaller, yet personal way, I also like the excitement the children always have, without fail, whenever there’s curry and rice for school lunch. It’s a feeling I know well, and one I wished I could have felt more often—a simple comfort and reassurance that things will be alright.

In a smaller, yet personal way, I also like the excitement the children always have, without fail, whenever there’s curry and rice for school lunch. It’s a feeling I know well, and one I wished I could have felt more often—a simple comfort and reassurance that things will be alright.

When I was seven years old, in America, I started going to Japanese language school every week on Saturdays. I had to endure this ongoing pissing contest of bullying and being bullied that people like me played when we were kids, kids that were also mixed and confused about their cultural identity. Anxious and uncertain, we tried to make others feel as small as we felt. We asserted our anxious little egos and tried making everyone around us feel inadequate.

People would make fun of my lighter skin tone and my easy-to-ridicule name. I had never thought much about these things until then, let alone as things worth ridiculing over, but suddenly they were front and center targets for my classmates. So I came up with my own vitriol to fire back with. Fighting back like that felt good initially, but I didn’t notice what it was doing to me—trapping myself in negativity. It felt good at first to tell my classmates struggling with Japanese how dumb they sounded speaking, how messy their writing was, and how they’d never improve either. But in the end, it just fueled my self-hatred and bitterness even more. Some people grow out of this mindset, and some people never do, staying insecure and resentful into adulthood.

I used to resent having to go to these extra school sessions every week, resenting my parents and resenting myself. Neither my mother nor father seemed to have fully thought about catering to what I wanted from my life and what best fit me. My parents weren’t perfect though—they had their own personal and identity struggles too. Plus, like all couples starting families, raising kids was a new experience for them, shaped by trial and error. They did what they thought was best for me, but I felt in the end there was something important about myself I wasn’t able to understand. As I got older, I realized that if I didn’t go to Japan and live there long enough to understand myself better, I would regret it my whole life. I would have an incomplete picture, half obscured. Knowing became existential, necessary, so I’m grateful that the JET Program gave me this opportunity.

At the end of the day, none of us mixed kids were or ever will be really Japanese. Determining if we were Japanese enough didn’t matter in the end. I used to long for some kind of clarity about whether I was this or not. Halfway between two opposites, feet off the ground, I envied people with a clear cultural identity. I realize only now that being mixed gave me a clear opportunity. Not many people would be able to see and appreciate the world like me. There were no mentors to help me figure out how to be self-confident. I was never going to be any one thing, and I think I always knew that, deep down. I think that my grandma knew it too. She never made me feel like I wasn’t enough, and I wish I appreciated that more back then. What I wouldn’t give to go back to that dusty room and tell her no meal will ever compare to her curry and rice. I’d have told her my future self would cherish those memories of being accepted and loved.

At the end of the day, none of us mixed kids were or ever will be really Japanese. Determining if we were Japanese enough didn’t matter in the end. I used to long for some kind of clarity about whether I was this or not. Halfway between two opposites, feet off the ground, I envied people with a clear cultural identity. I realize only now that being mixed gave me a clear opportunity. Not many people would be able to see and appreciate the world like me. There were no mentors to help me figure out how to be self-confident. I was never going to be any one thing, and I think I always knew that, deep down. I think that my grandma knew it too. She never made me feel like I wasn’t enough, and I wish I appreciated that more back then. What I wouldn’t give to go back to that dusty room and tell her no meal will ever compare to her curry and rice. I’d have told her my future self would cherish those memories of being accepted and loved.

There’s never been a real roadmap laid out for me, so I will just have to continue making my own.

Shou Seidai Yuan is a sixth-year ALT working in Ehime Prefecture, the land of citrus. He is originally from San Francisco, California. He spends his time cooking complicated multi-course meals and losing at video games. Eventually though, things come out alright.