Amber Bunnell (Tokushima Prefecture)

It was a misty Sunday in mid-October when I became an accidental pilgrim. From a temple perched on a mountaintop, an hour and a half away from my new home in rural Tokushima, I studied the mountain range below in awe, the way it stretched endlessly to the horizon. I’d left my car parked in a tiny lot on the side of a cliff, hiked through a bamboo forest, passed through an enormous temple gate and climbed a hundred stairs for this view. The air smelled sweet, like incense and rain. I could see my breath.

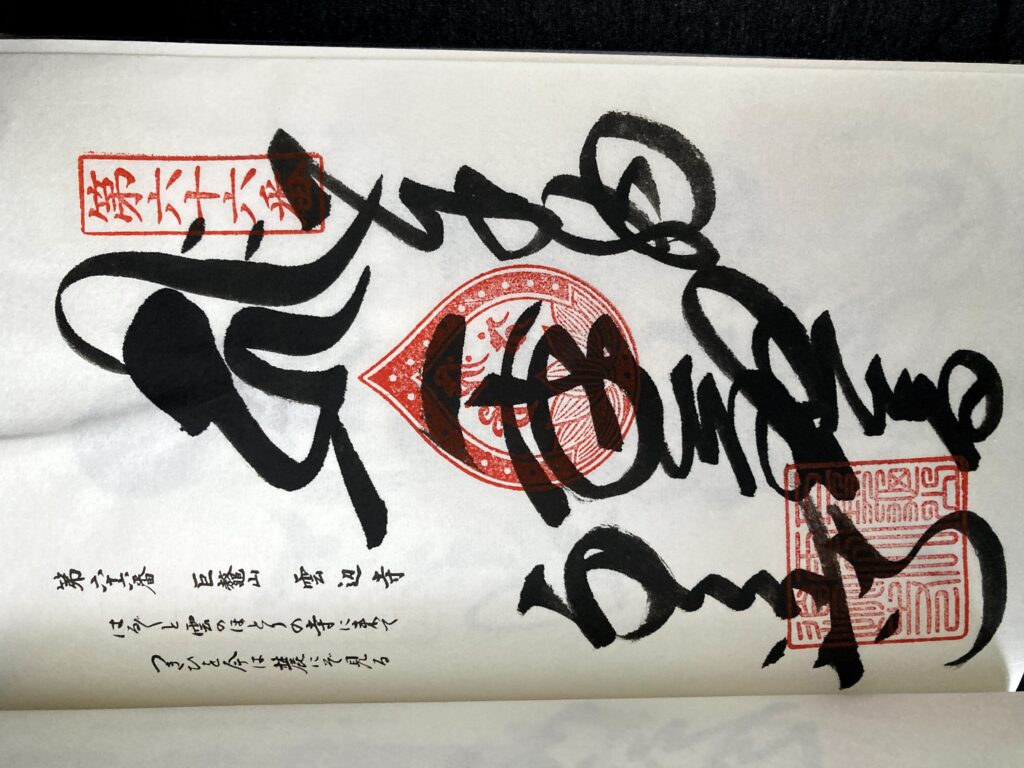

Earlier that day, I’d googled the Shikoku 88 Temple Pilgrimage on a whim and found the temple nearest me: Number 66. Unpenji. Later, inside the temple nokyosho, the small administrative office that sold things like omamori charms and engraved walking sticks, I eyed the different designs of the nokyocho pilgrimage books. They each had bright colors woven together in different patterns—some pocket-sized, some larger, all with 88 blank pages. I chose one with a deep blue background and red flowers. The temple staff signed it with a long calligraphy brush, in purposeful, unwavering strokes.

I didn’t consider myself a pilgrim, an ohenro (お遍路), yet. But this impromptu visit to Unpenji would set into motion a years-long journey around the wild, mesmerizing island of Shikoku.

A 1200-Year-Old Tradition

The Shikoku 88 Temple Pilgrimage is known as ohenro in Japanese, a word which can be used to mean both pilgrimage and pilgrim. It begins in Tokushima and circles Shikoku’s perimeter, stretching through Kochi and Ehime before ending in Kagawa. The 88 temples along the pilgrimage are a collection of sacred sites where the 9th century Buddhist monk Kobo Daishi (also known as Kukai) is said to have trained or visited (or been born, in the case of Temple 75, Zentsuji). As a young man, Kobo Daishi traveled to China and brought a collection of Esoteric Buddhist practices back to Japan, before establishing a monastery at the sacred site of Mt. Koya. He would later be known as the founder of Shingon Buddhism.

The 88 Temple Pilgrimage has been altered over the centuries before becoming the route we know it as today, but one thing has remained the same: there is no wrong way to do the pilgrimage.

The temples can be visited in any order. The pilgrimage can be completed in one go, or it can be broken into chunks and completed over time. Pilgrims travel by foot, car, bus, motorcycle, and bicycle. Some pay to go on guided tours. Some hitchhike, like a man from Hokkaido I met at Temple 29, Tosa Kokubunji; he’d been hitchhiking Japan for two years and was doing the pilgrimage a second time.

There’s also no wrong reason to become a pilgrim. Some become ohenro for religious reasons, or to pray for an illness to be healed. I once met an elderly couple in Kagawa—the wife with a headscarf wrapped around her short, lost hair, the husband steadying her with his arm as they meticulously lit incense. I don’t remember the temple number. I do remember praying for them.

Other pilgrims come out of an appreciation for the hiking trails and wild nature of Shikoku, or for self-discovery. And while you may see pilgrims in the traditional white jacket and triangular straw hat, there is no mandated pilgrim uniform.

No matter the reasons for your visit, there are some temple basics most pilgrims adhere to. Bow before entering through the temple gate. Find the basin of water near the entrance and use one of the dippers to wash your hands and mouth. All temples on the pilgrimage will have a daishido (大師堂), a hall in the temple dedicated to Kobo Daishi, and a hondo (本堂), or main hall. Make your way to one (or both), and place a coin in the offering box—five yen coins are the most sacred. Place your palms together, bow, and say a prayer (or recite your sutras). Finally, visit the nokyosho office and pay 300 yen to have the temple staff stamp and sign the corresponding page in your book.

If you’d prefer to simply wander the grounds, appreciate the architecture and the history of the ancient ground you find yourself on, that’s perfectly acceptable too.

Modern-Day Pilgrims

“Kobo Daishi was a great businessman,” my friend Naoko likes to say. “He saved the economy of Shikoku.”

It is undeniable that a robust industry has sprung up around ohenro, including bus tours, restaurants and souvenir shops in remote locales, and shukubo, temple-run inns for pilgrims. While the image of Kobo Daishi may be of an ascetic traveling alone with few worldly possessions, a substantial portion of modern pilgrims are driven by tourism. They want to experience the good food, beautiful views, and local hospitality of the island.

I admit that I owe a lot to Kobo Daishi. His pilgrimage has brought me to places I would have never discovered on my own. Thanks to him, I know that the seaside trails in Muroto, right below Temple 24, Hotsumisakiji, offer the most spectacular view of the sun rising above the Pacific Ocean. I know that the longest ropeway in western Japan spans a stunning green canyon in southern Tokushima, providing access to Tairyuji, Temple 21. I know that each October the neighborhood kids who live around Temple 39, Enkoji, perform a centuries-old dance dressed in gold pants, colorful scarves, and deer antlers.

Of course, the pilgrimage has connected me to people too. I’ve completed different parts of the journey with different people, and with different purposes in mind. The temples farthest from me, deep in the mountains of Kochi Prefecture, I explored with friends on a car trip. We spent the entire time laughing, taking photos of sunsets and waterfalls, turning the music in the car up as loud as it could go.

I visited the temples nearest me in central Tokushima alone, the day after my grandmother died. I drove for hours in silence. I don’t remember much of that trip except for the beauty of Temple 6, Anrakuji, where I tried not to cry while watching koi fish swim circles in a pond.

most of Kagawa on day trips with my partner, during the worst of the pandemic. We climbed hundreds of empty stairs leading up to the hondo, GO TO OHENRO posters plastered on bulletin boards around us. From the steep top of Temple 71, Iyadaniji, I thought, This is the man I want to spend my life with.

Most recently, I took a friend on medical leave from work with me to the Pacific coast in southern Kochi. At Temple 23, Shinshoji, we wrote prayers for her recovery on wooden blocks and then hung them in the wind, among dozens of other wishes. We were so close to the sea that the air around us was salty.

“Are you okay?” I asked her as we made our way slowly back down the stairs. She looked tired.

“Let’s do another one,” she said.

An Ongoing Journey

Despite being a fourth-year pilgrim, I often forget the rules of how to wash my hands and pray. In my early days visiting temples, I felt self-conscious about my lack of expertise, and was nervous about offending the other pilgrims or temple staff. Do I bow before or after walking through the gate? Which hand do I wash first?

But now, more than any precise Buddhist ritual, I know that the most precious thing about ohenro is the opportunity to feel everything.

Feel the cold water on your hands as you wash them at the temple gate. Smell the incense floating in the air as you make your way to the hondo to pray. Hear the brief clank of metal as your coin enters the collection box, and the chants of the pilgrims next to you reciting their sutras. Feel your prayer, whatever that looks like for you—eyes closed, palms together, thinking about God, or your family, or simply taking in the tranquility around you. For a moment, the rest of the world becomes quiet, 88 times.

Amber Bunnell was a JET from 2016-2019, based in Tokushima. She is a licensed English and Japanese teacher, and co-founder of Tsunagu Mima World Community. When not teaching or volunteering, Amber enjoys camping and travel, and is obsessed with onsen. Follow her at ambersensei.mima on Instagram.