This article originally featured in the May 2021 issue of Connect.

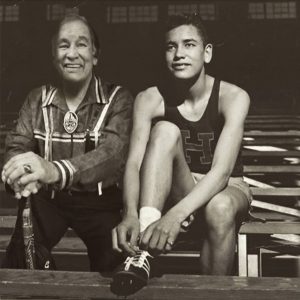

Billy Mills interviewed by Rashaad Jorden (Yamagata 2008-2010, Kochi 2018-2020)

Prior to entering the 1964 Olympics, Billy Mills was rather unheralded, but the native of South Dakota went on to produce one of the greatest upsets in Olympic track and field history, stunning world record holder Ron Clarke of Australia and defending champion Pyotr Bolotnikov of the Soviet Union to win gold in the 10,000-meter run. Mills set a then Olympic record to become the only American (to this point) to win gold in the event, a triumph that inspired the 1983 film Running Brave. Mills is the co-founder of Running Strong for American Indian Youth, an organ-ization devoted to enhancing the lives of Native Americans. In 2012, he was awarded the Presidential Citizens Medal by President Obama.

I had the privilege to interview Billy Mills in June 2020.

Was the 1964 Olympics the first time you visited Japan? If so, what excited you the most about coming to Japan for the Olympics?

It was the first time that I had ever been to Japan, and there were several things that excited me. When I was a little boy with my father on the reservation, we were driving. He’s fiddling with the radio, trying to get a clearer reception. Then he said, “We made a big mistake. We did a terrible thing.” And I thought he meant us. I said, “What did we do, Daddy?”

It was the first time that I had ever been to Japan, and there were several things that excited me. When I was a little boy with my father on the reservation, we were driving. He’s fiddling with the radio, trying to get a clearer reception. Then he said, “We made a big mistake. We did a terrible thing.” And I thought he meant us. I said, “What did we do, Daddy?”

I was finding parallels based on our prayer, “we are all related.”

He said, “We dropped a bomb on Japan. We should have given them a demonstration of the power [of the bomb]. We should not have dropped it. We should have demonstrated in another way the power of the bombing and what it could do.”

“It could destroy the world,” he added.

I said, “When is that explosion going to reach us?”

He said, “It’s not. But we could build a bomb that could destroy the world.” And he quoted the most powerful prayer of my Lakota tribe. He made a reference to Japanese people being our relatives. He said, “We are all related.”

I grew up learning about World War II and learnt a bit about Japan before I went [to the 1964 Olympics].

The Black Hills, which is an extension of the Rocky Mountains in the United States, is—in our tribal area—the heart of everything that is. As I learned about Mt. Fuji, I thought, “That must be the heart of everything that is to the Japanese people.” I was finding parallels based on our prayer, “We are all related.”

When we were flying into Japan for the very first time on Oct. 1, 1964, I could see Mt. Fuji, and I felt very comfortable spiritually; it was comforting that this must be the heart of everything that is for [Japanese] people.

Every Japanese citizen I saw, as our Lakota tribe teaches us to do, was humbling themselves to honor their family and their nation. If I could do that, I could honor the United States of America and then honor humanity globally.

It sounds like it was a very spiritual experience coming to Japan.

Going to Japan was very spiritual. Spiritual as in the story I mentioned, it was about honoring myself, honoring my tribal nation, and seeing the Japanese citizens honoring themselves and honoring their country. It was so powerful to me.

I went to the Olympic Games not to win a gold medal. I was struggling with racism in America. I came so close to taking my life in my junior year in college, and my Dad died when I was 12. [But] he told me, “Pick a dream. It will heal a broken soul.” I had wrote down, “Olympic gold medal. 10,000-meter run.” I used the Olympic Games as a journey to heal my broken soul. The 1964 Games allowed the citizens of Japan to dream, to help them heal on a global basis.

I want to promote global unity, dignity, character, beauty, global diversity.

During my first week in Japan, I read about the young people that were born in Japan on the day of the two atomic bombs. The theme of the Olympic Games, representing the youth and the world as one, was enduring.

That was a spiritual experience reminding me that, “We are all related.” My wife and I use that experience in our life journey now. I want to promote global unity, dignity, character, beauty, global diversity. Not only the theme of the 1964 Tōkyō Olympic Games but also the future of humankind.

What were you feeling when you toed the starting line for the 10,000?

I would call it a spiritual feeling. I was using the Olympics as a catalyst to heal my broken soul. So I line up at the start of the race. I’m in the second row, probably lane eight. I was confident that the race and victory was mine if I chose to take it. I had to believe that I could perform beyond my capabilities.

I was using the Olympics as a catalyst to heal my broken soul.

My wife was 95 meters back up the track. Probably 30 seats up. I knew where she was when we walked to the starting line. She knew then what I was trying to do. She knew I wanted to win.

I debated during a 25-mile run six months earlier [about getting a loan to take her to Tokyo]. After I finished that run, it was like, “Yeah, I need her there to win.” [So] we borrowed the money from a bank. $800 for a plane ticket and lodging at the Palace Hotel so she could be there with me.

Before the gun goes off, the thought of her 95 meters behind me crosses my mind and yes, I needed her. The victory was there. It was up to me to win.

Where did that confidence come from?

I think the confidence came out of high school. In my graduating year, I was the second-fastest two-miler in the nation and the fourth fastest miler. I did not know until Sept. 23, 1963 that I was hypoglycemic and type 2 diabetic. In high school, my coach said I was tired from not being rested. Not knowing anything medically, he started giving me honey before the races. The honey before the races kept my glucose level up. In college the coach said, “We do things differently. We eat four-and-a-half hours before competition.” So every race I ran in college, I went low blood sugar.

The doctor diagnosed me 12 months before the Olympic Games and I realized if I could control [the hypoglycemia], rather than being marginally elite—running like the best in the world and faltering at the end—I could beat them.

The talent was there. I had to find out what was keeping that talent from blossoming. I only had one world record. I trained through my world record. I didn’t rest. I wanted to compete in Europe against the Soviet Union. In July of ‘65, I wanted to go sub-27:40 in the 10k. No one had been under 28 minutes. Then [Australia’s Ron] Clarke broke 28 minutes, but I was ready to beat it.

I got sick and couldn’t compete. When I walked off the track on Aug. 12, 1965, I looked at my wife and said, “I will never be world-class again. It’s too difficult running hypoglycemic, borderline type 2 diabetic.”

I quit running on Oct. 12, 1965. So in retrospect, I feel—if I was running today—with the talent that I had against the best in the world today, I think I could still have not one but several world records.

If I could have handled that hypoglycemia back in the ‘60s, I would have been able to match Ron Clarke world record for world record. He had 18 of them. So I look upon my career as being number one, I healed a broken soul. That by far was the most powerful victory I had in my life.

It seems like healing a broken soul was more important than winning an Olympic gold medal.

Yes, and with probably about 80 meters to go, I knew I was going to win. My thought was, “I’m gonna win.” But following that was, “I may not get to the finish line first.” It meant I healed a broken soul. The journey, not the destination, is what empowers us.

It provided a healing process. And I was blessed because in the process I also happened to win a gold medal that no one else from the Western Hemisphere has won. But, healing a broken soul was by far the greater gift.

Far greater than healing the broken soul was the empowerment—spiritually and mentally—of Japan putting on the greatest Olympic Games in the history of the modern Olympic Games and what it did for the country. To me, that’s a miracle.

What were your impressions of Tōkyō as an Olympic host?

What were your impressions of Tōkyō as an Olympic host?

Tōkyō was the perfect host. Many countries have put on incredible Olympic Games, London, for example. The Japanese citizens were the perfect hosts; they went out of their way to help me and my wife Patricia. They tried to answer any questions despite the language barrier. The restaurants we went into, the volunteers at the stadiums, the humbleness and the respect they showed to us. I have a hard time describing it. It came from their heart.

Other than your gold medal, do you have any other favorite memories of the 1964 Olympics?

I have several beautiful memories that come from the ‘64 Olympics. One of them was being introduced to sushi and a Japanese fruit. It’s like a huge apple, a juicy fruit. It’s yellowish and similar to an apple. It’s the size of a grapefruit and very sweet. That fruit helped me win the gold medal because as I ate it, my blood sugar stabilised.

Another memory had to do with a candy bar. I was going low blood sugar before the race started, and I was panicking. I was trying to find someone who could get me a Coca-Cola or a candy bar. I felt I needed something in my stomach rather than fluid. A Japanese man had a candy bar. That candy bar helped me win.

A couple of other beautiful memories. I was speaking at a conference on sport as a culture in 1984 or 1985, and they were showing the movie Running Brave. There was this young man standing there very politely with a young lady. He stopped me and said he was named after me. He and his fiancee were getting married and going to America.

“We want to go across the United States by train, by bus just to see the heart of the country and when we get to California a month later, could we visit you?” he asked.

So my wife made arrangements for the young couple to visit us. Months go by and they visit us. As they are leaving Patricia asked, “Could you write your name down for us?” So he wrote his name.

Patricia said, “Well, what part is Billy?”

“My name’s not Billy,” he responded.

She said, “I thought you were named after Billy.”

He said, “Yes, I am. My father went to the Olympic Games—the 10,000-meter run—to watch the Japanese athlete (Kokichi Tsuburaya) who finished back in sixth and my mother goes into labor. I was born during the 10,000-meter run. My father was so taken by how you won the race. He named me after you but my name is not Billy.”

My wife goes, “What’s your name?”

He said, “My name means ‘The Noble One.’”

That moment in time touched me.

The journey, not the destination, is what empowers us.

Rashaad Jorden was a two-time JET participant—first in Yamagata Prefecture from 2008 to 2010, and in Kochi Prefecture from 2018 to 2020. During his JET experiences, he completed the Tōkyō Marathon in 2010 and the Kochi Ryoma Marathon twice, 2019 and 2020. He also served as the sports editor for CONNECT from September 2019 to July 2020.