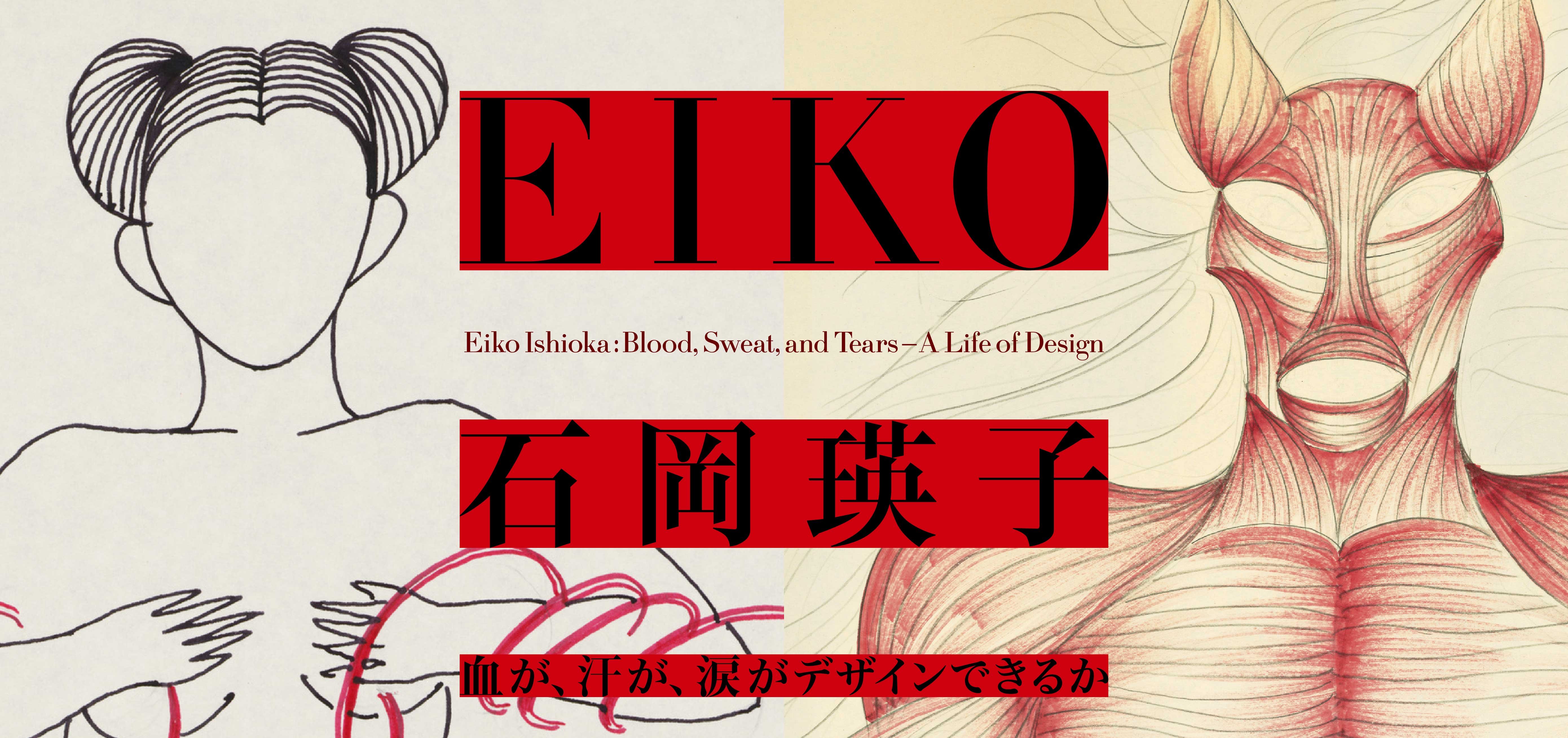

A Look Back At The Costume Designs of Ishioka Eiko

This article originally featured in the April 2021 issue of Connect.

by Rhiannon Haseltine (Hyōgo)

There are two common themes to the work of Ishioka Eiko: “big” and “red.” This is, of course, a massive oversimplification of her decades of legendary design work. In her early graphic design through to her later costume work, Eiko (as she preferred to be called) favoured boldness and intensity. She aimed, too, for timelessness—not in the sense of classic simplicity or minimalism, but in evoking both the future and past at once. Her ingenuity suggested a future not yet known; her use of the grotesque and erotic appealed to the most primitive parts of human emotion. And then there was the red, her signature colour—one a collaborator described to be as “strong, intense, [and] brilliant”[1] as Eiko herself. In a world that so often teaches women to make themselves small and unheard, Eiko and her work have commanded attention and space from the start.

A Life in Four Chapters

A Life in Four Chapters

Eiko, born in Tōkyō in 1938, began her career in graphic design at cosmetic giant Shiseido in the 1960s. Her father, otherwise encouraging of her creativity, had strongly discouraged it; being a graphic designer himself, he understood the hostility she would face as a woman. Indeed, Eiko had to insist even in her interview that she receive equal treatment to her male colleagues. Young women at the time were seeing a sudden increase in their power as consumers, and Eiko’s ad campaigns called to this newfound independence; empowering women who had been brought up “to listen rather than speak”[2] to see themselves as the directors of their own lives and experiences.

The women Eiko featured in her campaigns were, invariably, “big, big, big”[2] in both presence and visual impact, frequently nude, and emblazoned with slogans like “Girls Be Ambitious!” and “Don’t Stare at the Naked; Be Naked”[1]. She was known to feature models from India, Morocco, and Kenya, presenting a striking new ideal of beauty to a country notorious for its exaltation of porcelain-white skin.

A favoured muse of Eiko’s was American actress Faye Dunaway, pictured here in the 1979 poster “Can West Wear East?,” produced for department store Parco. Dunaway, clad in robes of shiny, silvery satin and an exaggerated headdress reminiscent of a nun’s cornette, stands (with wing-like seraphic, voluminous sleeves) between two young Japanese children. The little girls, Eiko’s nieces, have eyes daubed with red shadow and wear long, full red skirts tied at the chest that call to mind the hakama trousers worn by miko (shrine maidens). The effect is heavily evocative of religious iconography—a dreamlike image seeming simultaneously futuristic and primal. This seamless blend of western and eastern cultural motifs with archetypal imagery can be seen time and time again through Eiko’s work.

Can West Wear East?

Fearful of becoming stuck in a creative rut, Eiko left Japan for Manhattan in 1980;—a 15-month hiatus followed before she turned her attention to the cinematic and theatrical worlds of production and costume design. Between budgets, practicalities, and conflicting creative visions—not to mention the pressures from above to not stray too far from the profitability of safe, mainstream ideas—design for film and theatre is usually an exercise in compromise. Director Francis Ford Coppola, who worked with Eiko on Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992), wrote: “When you make a movie, you don’t get exactly what you want—you never do—you get percentages[.] Except for Eiko. She got what she wanted.”[1]

Eiko’s unyielding determination to realize her design ideas exactly as she envisioned them only made her more desirable to collaborate with. She was sought out time after time specifically for her uniquely surreal artistic vision; director Tarsem Singh stated that he “fell down on [his] knees” to get her to work with him.[1]

The themes of eroticism and spirituality evident in Eiko’s earlier work were also infused in her costume designs, from the gothic sexuality and decadence of Bram Stoker’s Dracula to the ominous Pagan mysticism of opera Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of Nibelung, or The Ring Cycle). She played with gender, cultural influences, and the human body itself, and also liberally incorporated animal motifs, historical elements, and references to other artistic works, seeking to visualize those most primal and visceral parts of the human psyche and experience. Her costumes reflected this even in their construction—being sometimes impractically heavy or otherwise uncomfortable to wear but always serving to represent the character’s psychology. Jennifer Lopez, while filming Singh’s The Cell (2000), requested that the hard plastic collar Eiko had designed for her be made more comfortable, only for Eiko to respond, “No—you’re supposed to be tortured.”[1] And although safe in practicality, Eiko’s spiked, angular costumes for the Cirque du Soleil acrobatic show Varekai (2002) were designed to provoke a sense of fear and danger in the audience.

“It was sometimes difficult for actors to wear Eiko’s costumes[.] They were heavy and constricting, and it could take three people to carry a coat. But look at the film in the end.” -Tarsem Singh, 2012.[1]

If it was a risk to hire “a weirdo outsider with no roots in the business”[1], as Coppola described Eiko, it was certainly one that paid off. Eiko’s innovation and unique imagination were handsomely rewarded, first in 1992 with an Academy Award for Costume Design (Bram Stoker’s Dracula), then in 1998 with two Tony Awards for Stage and Costume Design (M. Butterfly), and finally with a posthumous Academy Award nomination in 2012 for Costume Design (Mirror Mirror). Even those projects that proved less popular with audiences and critics could not be faulted on the basis of Eiko’s work—notorious Broadway failure Spider-man: Turn Off The Dark (2011) still saw praise for her surreal, sculptural costume design.

Blood, Sweat, and Tears

Analysing Eiko’s entire body of costume work in-depth would fill this entire issue of CONNECT, so let’s focus on the two films that earned her the attention of the Academy: Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mirror Mirror.

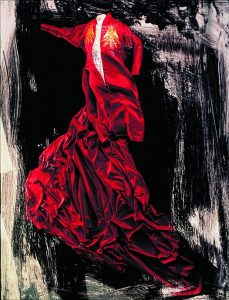

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, conceptualized by Coppola as “an opera with sex and violence”[3], took its sartorial influences primarily from Victorian garb—but by no means exclusively. This is evident in perhaps the most famous costume of the movie: the sumptuous, billowing scarlet cloak worn by Dracula (played by Gary Oldman). With gold phoenix and dragon embroidery on silk of Eiko’s signature red, the dynastic Chinese inspiration is clear. The rich fabric and trailing length exude power, wealth, and sensuality, and—of course—the bloody colour evokes vampirism without resorting to more well-worn costume tropes.

Another particularly enduring image from the movie is that of Lucy’s (Sadie Frost), post-vampiric transformation. Her enormous lace colour calls immediately to mind a frill-necked lizard’s mid-threat display, evoking ideas of danger and cold bloodedness. She wears what had been her pre-transformation wedding dress—a shapeless, lacy bohemian gown. Pre-transformation Lucy is a flighty, flirty socialite, quite in violation of Victorian social norms. Her seductive nature is represented with sheer fabrics, bare shoulders, and even cleavage—gasp, shock, quelle horreur. . . . Her later fate is hinted at with reptilian touches, such as the embroidered snakes patterning one of her gowns.

Flipping to the other side of the Madonna-whore coin, Winona Ryder’s Mina is the poster child for Victorian femininity—a pure and innocent ingenue clad in soft greens and leafy motifs. Given that she is the (spoiler alert) reincarnation of Dracula’s centuries-lost love Elisabeta, the crown of acanthus leaves she wears in one scene is a nice touch, as acanthus symbolizes immortality and eternal life.

Flipping to the other side of the Madonna-whore coin, Winona Ryder’s Mina is the poster child for Victorian femininity—a pure and innocent ingenue clad in soft greens and leafy motifs. Given that she is the (spoiler alert) reincarnation of Dracula’s centuries-lost love Elisabeta, the crown of acanthus leaves she wears in one scene is a nice touch, as acanthus symbolizes immortality and eternal life.

Mirror Mirror, in stark contrast, has the timeless fantasy feel of “a true fairytale”[3], a delightful mix of eras. Costume elements were chosen not for historical accuracy but instead for establishing character. Snow White (Lily Collins) appears first in pastel colours and festooned with flowers, the bust-flattening 16th century bodice and 19th century poofy sleeves serving to emphasize her innocence and childlike nature. This is further emphasized later in her ballgown of purest white with angelic wings and a swan headdress.

The swan imagery works primarily to under-score the contrast between the understated elegance of Snow White and the extravagant vanity of the evil Queen Clementianna (Julia Roberts). The Queen’s crimson ballgown features silvery peacock motifs and an absurd feathered collar. Her costumes throughout the movie pull mostly upon the fashions of Tudor and Elizabethan nobility, with huge collars, voluminous sleeves, and skirts up to eight feet in diameter. As it was throughout history, this ostentatiousness is a demonstration of immense power and wealth—a silent message to potential enemies that the Queen is not one to be trifled with.

Timeless, Original, Revolutionary

In both her graphic design and costume design, Eiko viewed art’s purpose as not for its own sake but for the visual communication of a message. Eiko described it as ”a language to convey oneself.”[4] Nevertheless, collaboration, rather than limiting her self-expression, opened new avenues for the realization of her vivid ideas.

Eiko died, before the release of Mirror Mirror, of pancreatic cancer at age 73. Singh reported her as being seriously ill during filming, but no less intense and dedicated for it: “Her work kept her alive—it was her reason for being.”[1]

Eiko recounted once being told by a male designer that she was only famous because she was a woman in a male-dominated field, implying that her work was otherwise insignificant. [1] The body of work she left behind proves this statement laughably false. Her bold, visceral design language was inimitable, going far beyond anything expected or safe. She made her big, red mark on the design world, and it’s one that won’t be forgotten.

Sources

1. http://bit.ly/2ONhZwT

2. http://bit.ly/3csmLb9

3. http://bit.ly/38yJxgi

4. https://bit.ly/2NcAJoS

Rhiannon recently returned to her hometown of York, UK, after spending 2.5 years on the JET Program. She has a degree in Costume Design & Making, a fact that still surprises her given how bad she is at sewing. She enjoys traumatizing herself with horror movies and misses Sushiro more than words can say.

Top photograph: Photo found on Mot Art Museum website – Eiko Ishioka, Costume design for the movie Mirror Mirror (Directed by Tarsem Singh, 2012) ©2012-2020 UV RML NL Assets LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Bottom photograph: Photo found on Mot Art Museum website – Eiko Ishioka, Costume design for the movie, Mirror Mirror (Directed by Tarsem Singh, 2012) ©2012-2020 UV RML NL Assets LLC. All Rights Reserved.