This article originally featured in the February 2021 issue of Connect.

Nathaniel Reed (Niigata)

Note: Oftentimes when we read something in an article or blog, we find some useful knowledge but quickly forget where we read it. This usually results in us not acting on anything we read. This piece was written to empower you and is not meant to be stored away somewhere in your subconscious. One way of making this piece more useful to your future self is by including a number of references for you to follow. It is important to understand where you teach, who you teach with, and who you teach. Ultimately, a more effective teacher is a better result for everybody.

It’s 2021, and there are 20,000 Assistant Language Teachers (ALTs) in Japan. Despite that, the language competency of students in Japanese public schools, for decades straight, has been one of the lowest in Asian countries: currently trailed only by Laos and Tajikistan (Sawa, 2021).

So, why do our students consistently rank at the bottom of all international language tests like TEFL, TOEIC, IELTS, PISA, etc.? Furthermore, are ALTs to blame for this? For anyone that has taught in Japan, even for just a short time, you’ll know the answer is ‘no’. There are many ‘barriers’ (a word borrowed from Kano et al. 2016) to us teaching effectively, including the ‘one-shot’ system, lack of structured teacher training, hiring standards and the English competency of our co-workers.

What’s stopping us from delivering a high standard of language education?

The ‘one-shot system’ is the phrase that describes the number of places we work at: we don’t work in one school but in any number each week or month. The one-shot system has been in place since the beginning of the current ALT system, which started in 1987. The regularity with which we teach each class and the agency to impact learners’ language learning progression are significantly hindered by this. To put it clearly, one may work at five different schools each week with 15 classes in each school, which is 70 classes in total. For example, you’ll see class 1-1 in school one about every 6 weeks, maybe 8 times in an academic year. Can you really affect your student’s level of English in this context?

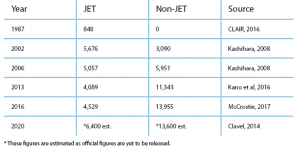

Another barrier is the lack of structured teacher training. Of the 2,000 ALT employers, few provide pre- or in-service teacher training. Those that do train their teachers offer between zero and five days of pre-service training, and any in-service training ranges from once-a-month meetings to once-a-year conference-style events. While some existing training is conducted through professional teacher trainers, most still rely on teachers sharing ideas with one another. The lack of direction from the ministry is shown in the hiring patterns of ALTs. One way of reading the table below is noticing the shift to more private and direct hire ALTs that generally acquire more training than the orientation and annual SDC offered by CLAIR.

We are all, and truly, in the age of ‘open access’ where people can share their opinions on things to the whole world, on multiple platforms, with the click of a button. And so these ‘barriers to effective teaching’ are found all over the internet, and not just in academic articles, and books, but tweets, Facebook posts, YouTube, etc. People are sharing negative aspects of our position (such as the one-shot and lack of training) with ease. Just type ‘ALT’ in Google to see for yourself (for a recent paper looking at ALTs writing online see Borg, 2020).

Behind the barriers to our effective teaching?

Perhaps the main reason why our training standards are like they are is because of the lack of a job description. The Ministry of Education has never provided a detailed description of our job. In the 2008 Course of Study (the syllabus from the Ministry of Education), our position is just a footnote: ‘ALT stands for Assistant Language Teacher. An ALT is a foreign helper to be employed for foreign language education at schools. ALTs are supposed to work along with school teachers for “team teaching.”’ (MEXT, 2008). Without a detailed job description of ALTs’ roles and duties, employers have little guidance on how best to prepare teachers.

Awakening

Japan is a different place than it was in 1987 when the political agreement to bring unskilled non-Japanese people to Japan as teachers was made. Daniel Ussher’s video on YouTube titled ‘JET 30 years On: Still Meeting Needs?’s a simple summary that paints a picture of how Japanese society is completely different from what it was in 1987 (Confident English, 2018). He mentions a couple of important points, including how other school teachers and parents are tired of the current outdated ALT system and prefer qualified teachers to teach children in Japan.

Some examples of how the teaching landscape has changed include:

- By 2015, 3,079 ALTs were Japanese nationals.

- The number of non-Japanese ALTs with teaching credentials, Masters degrees and PhDs, and who have worked in this role for more than two or three decades is technically unknown as such records aren’t kept. But, the numbers are in the hundreds (possibly thousands) as my research over the last 6 years has found.

- There are ALTs who have been teaching since before the JTEs they work with were even born.

- More universities are training non-Japanese people (mostly former ALTs) to be teachers. Perhaps ‘J’ should be dropped from ‘JTE’ as ‘Japanese’ Teachers are increasingly not Japanese.

- Media and online platforms are exposing the realities of school life and educational standards. For example, stories feature ALTs who work with JTEs they used to teach in eikaiwas.

- As the foreign community in Japan is in the millions now, social media is flooded daily with comments from people about the number of English mistakes on handouts, mock tests and notebooks that their children bring home from school.

- BoEs have been publicly expressing their frustration at the institutional constraints in sending untrained ALTs to work in schools for some time (Tope, 2003).

However, the modern reality of vastly more experienced and qualified ALTs deserves official recognition. There is a growing army of very capable teachers that could support their learners in getting better results, and who can train other teachers.

From at least the late 1990s, research has consistently found that ALTs are not teaching in assistant capacities but teaching on their own (McConnell, 2000. AJET, 2014. Walter & Sponseller, 2020). Should the ‘A’ be dropped from ALT too? This can be viewed from at least two angles: teaching unaided with no experience, qualifications, or training is less likely to improve student language competencies. However, ALTs with credentials are a good thing for improving learner competencies. Views of JTEs follow this line of inquiry, too. They are increasingly stating that they prefer working with qualified and skilled teachers, with comments such as ‘Teachers leave just as they’re getting good,’ and ‘Getting a good ALT is like winning the lottery’ (Clavel, 2014). Other JTE comments include ‘Ideally I’d like the ALT to be the main and the JTE to assist’ (Walter & Sponseller, 2020), which is quite a common finding these days.

You’re probably reading this thinking ‘Of course teachers need training. Nothing new here’. And you’d be right. I’m certainly not the first to say that ALTs need higher quality and specific training. So, let’s revisit the original question: are ALTs to blame for low standards of English education in Japanese public schools? The answer is ‘no’. However, to what extent could ALTs improve the foreign language learning competencies of Japanese students?

Previous Training Initiatives

In 2010, Dr Chizuko Kushima and others set up an online venue for ALTs to ask each other questions about the job and build a community of peer support (Kushima, 2011). The Sendai Board of Education also has a solid ALT training system. They hire teachers with five years of experience and provide regular team training with both JTEs and ALTs (Crooks, 2001 and K. Hill, Personal communication, November 29, 2016). Numerous other researchers have put forward a large variety of ways to effectively train teachers. You could see Tajino & Walker (2010); Luxton, Fennelly and Fukuda (2014); and Machida (2019) as some accessible examples. While there have been previous successful ALT training initiatives, and countless ex-ALTs (now working in universities) have researched what to include in the training, there was no resource that consolidated all the research together.

And, it takes a group to put these together and do it. But how?

Providing Training for all ALTs

In 2015, I finished an MA in Linguistics, done completely online. My eyes were open to online learning and training. Whilst writing my dissertation, I got the ALT job and quickly became motivated to improve the level of training provided and to raise the standard of language education in Japanese schools. So, I got to it, and ALT Training Online was born. But how in the world would I put a complete training programme together, keep it free, and maintain the highest quality standards?

I had been a member of The Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT) for some time, and within JALT I could network with textbook writers, MEXT officials, teacher trainers, ALT researchers, online teaching specialists who were mainly all ALTs back in the day. I asked many people to contribute in various ways and always received positive responses. These people write the courses for ALTTO, contribute blogs, proofread our work, act as consultants and much more. Without JALT members, ALTTO wouldn’t exist.

Through JALT, I’ve built relationships with numerous JETs mainly at the international conference in November. Since 2010, AJET and JALT have had a reciprocal affiliation agreement, meaning that JETs get a pass to present at the annual conference. I’m sure that this agreement is why I’ve seen a clear rise in the number of ALTs attending the November conference. This steadily rising number is further motivation to supply training, as ALTs are actively seeking professional development.

Creating ALT Training Courses

ALTTO has courses ranging from how to effectively teach the four skills (listening, reading, speaking and writing) to teaching special education, CLIL, vocabulary, ICT and more. The order of courses is meant to be linear, as the skills and knowledge in the later courses build on to the earlier courses. But, depending on background and interest, courses can be completed in any order. The content of the courses is pitched at around the graduate level as a continuation of ALTs’ undergraduate backgrounds. We also considered people who have completed TEFL or CELTA type courses, and our content compliments those, too.

My MA was all text and a lot of reading. Knowing that completion rates of online courses are below 10%, we worked hard to develop features that assist ALTs to complete the courses. Our primary way of delivering content has been to provide multimedia and strategically placed reflection questions. Some courses are more text-based while others use more video and audio so that different learning styles are accounted for. The courses are constantly evolving too. Feedback from ALTs on course content is used to edit course content: the feedback loop ensures our courses remain relevant.

ALTs Connected

The courses form the complete training, but that’s not what it’s all about. Remember that there are over 2,000 ALT employers, and there is no communication (or standardised training) between them. Any training must be complemented with network building and social relations. So along with the courses, the 3,000+ ALTs currently subscribed to ALTTO make wide use of our various platforms including Facebook, Line, and LinkedIn. The army of very qualified and experienced ALTs play a key role here in responding to queries and shaping discussions.

ALTTO Blogs and ALT writers

On top of the above, we have a guest blog. Writers range from ALTs sharing ideas and experiences, to book writers, universityprofessors , researchers, teachers with specialised teaching approaches and more. My knowledge base has grown substantially by reading them. The various topics have molded and shaped various aspects of my teaching. If you feel you have something to share, contact our Blog Editor, David!

Here’s a call for your input. The bulk of the articles and books on ALTs (a couple mentioned above) are generally written by university faculty, and not always because they are motivated to improve teaching standards. However, each year there are a handful of published articles by ALTs themselves (e.g. my latest paper, Reed, (2020)). These articles are read by all kinds of people and sow the seeds of change. Publishing also gives writers more strength on their resumes. One additional goal of ALTTO is to encourage and fully support ALTs in both conducting research and writing up their work (for publication in a quality blog or elsewhere). The final two courses on our site provide full support on how to do this. The Doing Research module was written by a widely published researcher who has written about ALTs numerous times. The Getting Published course is written by a widely published author on education and former editor in chief of an international teaching journal.

Join the ALTTO Team

Currently there are six people on the ALTTO team keeping everything together, and we are always looking for more to come on board to help steer teacher professional skills and to support the other 20,000 ALTs. As more ALT employers are using our training (provided for free), and users grow, we’re actively looking for new people to join the team. Contact me to say ‘hi’ and become a part of the change.

Nathaniel Reed has been an educator since 2001, working in many countries around the world before settling, unexpectedly, in Japan. A keen tap dancer and dedicated father of two little angels, he’s reminded everyday of the importance of delivering high quality education and his mission of continual improvement.

References

- AJET. (2014, June 16). Assistant Language Teachers as Solo Educators.

- org, P. (2020). The JET Programme’s DeFacto ‘ESID’ policy and its consequences: Critical perspectives from the online ‘ALT Community. Gifu University Collection of Papers, 53(3), 41-59.

- LAIR, (2016). History. The Japan Exchange and Teaching Programme

- Clavel, T. (2014, January 5). English fluency hopes rest on an education overhaul. The Japan Times.

- Confident English. (2018, May 23). JET 30 Years On: Still Meeting Needs? JALT International Conference 2017. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ho_OJ-JSKN4&t=1005s

- Crooks, A. (2001). Professional development and the JET program: Insights and solutions based on the Sendai city program. JALT Journal, 23, 31–46.

- Kano, A., Sonoda, A., Schultz, D., Usukura, A., Suga, K., & Yasu, Y. (2016). Barriers to effective team teaching with ALTs. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & H. Brown (Eds), Focus on the learner. Tokyo: JALT.

- Kashihara, T. (2008). English Education and Policy in Japan. 12th OECD-Japan seminar “Globalisation and linguistic competencies: Responding to diversity in language environments”.

- Kushima, C., Obari, H., & Nishihori, Y. (2011). Global teacher training based on a multiple perspective assessment: A knowledge building community for future Assistant Language Teachers. International Journal of Information Systems and Social Change, 2(1), 5-8.

- Luxton, R. Fennelly, M. Fukuda, S. (2014). Survey of ALTs and JTEs. Shikoku University, 42, 45-54.

- Machida, T. (2019). How do Japanese Junior High School English Teachers React to the Teaching English in English Policy?, JALT Journal, 41(1).

- McConnell, D. (2000). Importing Diversity. California University Press.

- McCrostie, J. (2017, May 3). As Japan’s JET programme hits its 30s, the jury’s still out. The Japan Times

- MEXT. (2008). Chapter 3: Measures to be implemented comprehensively and systematically for the next five years.

Retrieved from here. - Reed, N. (2020). Teacher Views of Teaching English through English (TETE) in Japanese Junior High Schools: Findings from the Inside. The Language Teacher, 44(6), 35-42.

- Sawa, T. (2021, January 21). Japan going the wrong way in English-education reform. The Japan Times.

- Tajino, A., & Walker, L. (2010). Perspectives on Team Teaching by Students and Teachers: Exploring Foundations for Team Learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 1(1) 113-131.

- Tope, A. (2003, October 23). Japan rethinks ‘goodwill’ assistance. The Guardian.

- Walter, B. R., & Sponseller, A. C. (2020). ALT, JTE, and team teaching: Aligning collective efficacy. In P. Clements, A. Krause, & R. Gentry (Eds.), Teacher efficacy, learner agency. Tokyo: JALT.