This article originally featured in the October 2020 issue of Connect.

by Rebecca Paterson (Kyoto)

愛や復讐のために

THREE HAUNTING TALES TO START YOUR HYAKU MONOGATARI

Cooler temperatures, crisp autumn skies, and shorter days—the traditional spooky season of Japan has long passed with the end of Obon in mid-August, but, for many of us, this gradual decline into the lifelessness of winter brings with it the anticipation for our own festival of the dead. For this year’s Halloween, how about something a little different? Japan is well known as a country of rich paranormal traditions, diverse folklore, and terrifying filmography that both haunts and delights the imaginations of all. For those of us who enjoy the thrill of fear, one ghost story isn’t enough. But what about one hundred?

Hyaku Monogatari (lit. one hundred stories) is a form of entertainment that grew in popularity during the Edo Period (1603-1868). A group of friends would bring a mirror into a dark room, then light one hundred different candles around it—though nowadays electric lights, TVs, and phones also suffice. One by one, each person would tell a ghost story. Upon finishing each story, a light would be extinguished.

Much like a seance, tension, excitement, and fear escalate with anticipation as the room slowly dims. When all 100 frightening tales have been completed and the storytellers are finally enveloped in darkness, a spectre is said to appear in the mirror.

If you’d like to try Hyaku Monogatari yourself this Halloween, here are three of Japan’s extraordinary supernatural tales to start you off:

YOTSUYA KAIDAN

YOTSUYA KAIDAN

In Yotsuya, Tokyo, there was once a masterless samurai named Iyemon who desired to marry a beautiful woman, Oiwa. However, her father was aware of Iyemon’s unsavory character and refused his request. In a rage, Iyemon murdered him and blamed the crime on bandits. Iyemon then convinced Oiwa to marry him by promising to avenge her father’s death.

Their marriage was not a happy one. Growing increasingly frustrated with his life of poverty, Iyemon began to direct his pent-up anger onto Oiwa. As his feelings of resentment grew, he began an affair with a wealthier woman, Oume. Together, they conspired to murder Oiwa in order to marry. Oume prepared some poison and Iyemon then gave it to Oiwa, claiming it was makeup. However, the poison did not kill Oiwa, and instead left her face mangled and bleeding; her left eye began to sag, her skin scarred, and her hair fell out. Disappointed with his failed attempt to kill her and growing disgusted with his wife’s face, Iyemon bribed a local man, Takuetsu, to rape Oiwa to provide a grounds for divorce. On the night Takuetsu attempted to commit his crime, he was put off by Oiwa’s ghastly appearance. In response to her disbelief, Takeutsu showed her a mirror, and she flew into a rage, grabbed the nearest sword, and attempted to kill him. In the ensuing struggle, Oiwa fell and cut her own throat.

Iyemon finally succeeded with his engagement to Oume, but on the night of their wedding an apparition of Oiwa appeared before him. Panicked, he unsheathed his sword and cut off the spectre’s head—before the vision disappeared, revealing the decapitated body of Oume. Iyemon was shocked at his heinous mistake and fled the room. Before him, again, appeared Oiwa, and, again, he slashed at the phantom. This time, however, Iyemon had slain his father-in-law. With no way to redeem himself, Iyemon purged his bride’s family and fled from the town. Wherever he went, he was pursued by the ghost of Oiwa, her face manifesting in lanterns, and her dishevelled hair attempting to ensnare him.

Descending into madness, Iyemon fled into the forest, where he was eventually hunted down and killed by his brother-in-law.

It is said that Oiwa still haunts to this day.

Yotsuya Kaidan’s ghastly imagery and relentless haunting of the wronged Oiwa make this one of, if not the most, famous ghost stories in Japan. First told in a masterful and grisly Kabuki production, Yotsuya Kaidan gripped the imagination of the masses of the 19th century. Even now, Oiwa’s image has defined what we associate with modern Japanese ghosts—vengeful, unrelenting, and grotesque.

BOTAN DORO

BOTAN DORO

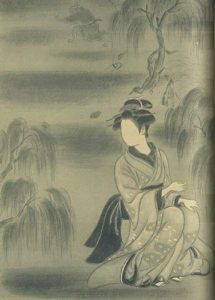

On the first night of Obon many years ago, a man named Hagiwara Shinzaburo was out walking, enjoying the local festivities. On his way home through the dark woods, he saw a peony lantern moving slowly in his direction. The owner was a maid accompanying her mistress—a young, beautiful woman—on a nighttime stroll. He was immediately enchanted by this woman, Otsuyu. They arranged to meet again, and before long, Hagiwara and Otsuyu had fallen passionately in love and spent every night together.

One night, a neighbour, woken by the light of the peony lantern and concerned at Hagiwara’s visibly deteriorating health, went to visit Hagiwara’s dwelling. Peeping through a gap in the sliding doors, he saw Hagiwara nestled in the bones of a skeleton. Terrified of the sight, the neighbour hurried to find a Buddhist priest for advice. The priest warned Hagiwara of the perils of mingling with the dead and gave him a talisman to protect his home against evil spirits. It proved to be effective.

Distraught with being separated from her love, Otsuyu came to Hagiwara every night, calling his name beneath his window and beckoning him to reunite with her. Eventually, Hagiwara was no longer able to resist the temptation and left the safety of his home. He disappeared into the night. The next morning, his body was found laying over a gravestone, embracing the skeleton of a young woman.

Botan Doro (lit. The Peony Lantern) originated in China as one story of the Buddhist moral text “Jiandeng Xinhua.” It came to Japan in the 17th century and rose in popularity after its publication in Asai Ryoi’s “Otogi Bōko.” Part of its popularity was thanks to its unique balance between passion and horror—juxtaposing beauty and romance with terror and death. Beginning with what sounds like a delightful love story, the story transforms with the neighbour’s nighttime investigation, shocking audiences with the striking image of a human skeleton. Some audiences may have even felt sympathetic to Otsuyu—unable to move on and stuck lingering in the world of the living in hopes of finding love. All these emotions make Botan Dōrō an unforgettable tale.

MUJINA

Long ago, on Akasaka road, Tokyo, there was a slope called Kii-no-kuni-zaka. On one side was an imperial residence surrounded by a deep, wide, old moat. After nightfall, the slope was poorly lit, so the darkness was quite unnerving. Despite its convenience as a shortcut, people would avoid this slope because of the mujina, and the most recent account is as follows:

One night, an old merchant was hurrying up the slope when he saw a woman by the moat, weeping profusely into her kimono sleeves. Afraid that she might be contemplating drowning herself, the merchant ran over to see what was wrong. She ignored his questions and continued sobbing, so instead, the man urged her to go home, fearful of what might be lurking in the dark. She slowly turned around, still covering her face, and turned towards him. She slowly removed her sleeve from her face and revealed nothing—no eyes, no mouth, no nose. The man screamed and scrambled up the slope, fleeing into the darkness. Not once looking back, he eventually saw a light ahead and ran over to it, only to find a soba-seller setting up a stall for the night. The seller, concerned, asked him what was wrong and whether the merchant had been attacked, to which the merchant replied that he had only been scared. The soba-seller asked what scared him, but the merchant could not explain what it was.

“Was it something like this?” asked the soba-seller, stroking his face and revealing a smooth surface with no features.

“Was it something like this?” asked the soba-seller, stroking his face and revealing a smooth surface with no features.

The lantern went out.

This version of the mujina, also known as nopperabō, came to prominence thanks to its inclusion in Lafcadio Hearn’s famous collection of ghost stories—“Kaidan” (1904). Although the mujina initially appears as a beautiful young woman, evoking imagery from stories like Yotsuya Kaidan and Botan Dōrō, this may not be the true form of the mujina. In fact, many would not call her a ghost at all. The mujina can shapeshift—we see it here as both the young woman and the male soba-seller. Rather than being classified as a ghost (yūrei), the mujina is a monster or ghoul (yōkai), much like the kappa or the rokurokubi.

Now you have the first three of your 100 tales. Will you move onto the fourth? For those who do, when you go to turn off the final light, just be wary of what might be lurking in the darkness, listening to your stories. . . .

Rebecca Paterson is a first-year PhD student living in Kyoto. After studying Japanese Studies in the UK and finishing her undergraduate studies with a dissertation about Japanese ghosts, she came to Japan to pursue her passion for language-learning and psychology. Rebecca still enjoys a good ghost story but can’t bring herself to watch any films because the visuals are too scary.