Amberly Young, ALT in Fukui Prefecture

Driving down meandering roads along the Sea of Japan, I felt a mixture of fear, homesickness, and excitement. I was heading for a week-long homestay on an oyster farm and guesthouse in Kumihama Bay, a tiny town that none of my Japanese friends had ever heard of. I knew that at least one person there spoke English, but I hadn’t met him.

I felt powerful yet terrified. What was I doing? I could be with my family in California. “You better be here next year!” The words of my grandmother during my last phone call home echoed in my mind.

Thanks to Google Maps, I had a location that I was driving toward, although I couldn’t read the name of the place I was going. All I knew was that a man named Atsushi had agreed to host me through the Help Exchange program (helpx.net) that I had used before in New Zealand and Australia.

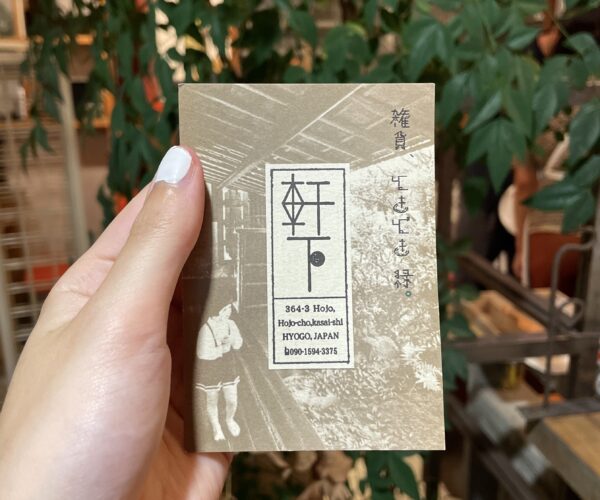

I arrived at a house with an indecipherable sign. Looking at my phone, and then at the sign, it seemed as if the two mysterious kanji might be the same. I sat in the car for a few minutes, gathering my courage and telling myself, “Get up. Get out of the car. Get up. You can do this.”

A full five minutes later I stepped outside into the freezing dusk. To my left, I could see Kumihama Bay and a deck with two dark figures in blue suits spraying water at some crates. “One of them must be Atsushi,” I thought to myself. “Maybe I should just wait for him to finish…”

But my legs betrayed me. I was already walking towards their front door when the grandparents spotted me.

“Ey! Konbanwa! We-ru-ko-mu! Watashiwa Tatsuo.” A wrinkled, grinning man came forward to shake my hand, American-style. “ここでなにしてるの?はは!じょうだんだよ!わたしたちのいえへようこそ!”

I blinked, confused. I couldn’t catch anything he had said.

“Oh no, not another one who can’t speak Japanese,” said his wife, a stocky, strong-looking woman. At least that’s what I thought she said.

“Oh no,” I thought to myself. “No one speaks English here. I’m doomed…”

“Kuruma? Pah-kin-gu? Doko?” The grandpa gestured for me to come — I think he wanted me to move my car to another parking spot. As I walked to my car in the darkness, wondering how I was going to survive the next week with my infantile Japanese, an angel appeared. Another foreigner was walking toward me on the street, frizzy red hair spilling from her winter cap. Hallelujah! I had no idea there would be another foreigner here.

“Hi, I’m Gosia,” she said. She helped translate for me what Grandpa was saying, and hopped in my car to direct me to the right parking spot. Later, I found out she is from Poland and has a master’s degree in comparative cultural studies with an emphasis on Japan. She has a one-year working holiday visa for Japan, and had already been volunteering on this oyster farm for almost a month. Gosia was my savior for the next week as I tried to adjust to the family and their habits.

Later, while drinking tea and attempting small talk with the grandparents in the kitchen, the door opened. In walked Atsushi, a tall and smiling man, looking windswept from working outside all day. He introduced himself enthusiastically in perfect English, and I immediately felt at ease. We would have many deep conversations in the next week. He showed me to my private room, made sure I knew how the heater worked, and asked me to try on my work uniform.

The ridiculous but very practical clothes he loaned us were blue overalls with thick, waterproof pants and a jacket underneath. Gosia and I joked that we looked like Mario.

The ridiculous but very practical clothes he loaned us were blue overalls with thick, waterproof pants and a jacket underneath. Gosia and I joked that we looked like Mario.

The next morning, after a breakfast of granola and fruit, Atsushi assigned us our tasks, and took time to carefully explain what he wanted us to do. My job was to pack oysters into boxes, weigh them, and put stickers on the boxes to be sent to customers. It was a task similar to an easy puzzle, and I found it quite relaxing. When I finished a box, I would carry it to the grandmother, Ayako-san, in the kitchen, and have a brief exchange where she would offer me tea and a break. I would politely refuse and keep working.

My spirits were further lifted by Atsushi’s kindness. Every time he walked by, he would greet me with a smile and say something like, “Thanks so much for being here. You’re helping a lot! You’re an important part of the team.”

This ten seconds of his time did wonders for my state of mind, and I’m sure I became a more productive worker after his encouragement. I decided then and there that if I am ever in charge of other people, I’m going to frequently and genuinely let them know how much I appreciate their hard work. This was the first of many moments when I realized that Atsushi was much more than a simple oyster farmer.

Atsushi had loved English in junior high and high school, and he attended college for architecture in Osaka. When he was 22, he lived in Canada for a year and his thinking totally changed. “When I was in Canada, my world expanded more than 100 times,” he told me. He came back and worked in Japan for a while, but he soon went to Australia for a one-year working holiday visa. Six months into his trip, he started receiving letters from his family asking him to come back to Kumihama. Since he is the eldest son, it is Japanese tradition for him to inherit the family business and help his parents as they get older.

Now, he helps his parents, Ayako-san and Tatsuo-san, with their minshuku, or Japanese guest house. He also runs the oyster farm that has been in the family for three generations. His grandmother used to row out to the platforms in a wooden boat.

During the week, I had many eye-opening conversations with Atsushi about a range of topics from the politics of fishing to the failing education system in Japan.

During the week, I had many eye-opening conversations with Atsushi about a range of topics from the politics of fishing to the failing education system in Japan.

Thanks to advice from a foreign friend, Atsushi discovered the Help Exchange program, where he could invite travelers to stay at his house for a few weeks or months at a time. People volunteer in exchange for room and board. This is a win-win situation for everyone: travelers are happy to contribute to his family, learn new skills, and live in a beautiful place for free, while Atsushi gets free help with his oyster work as well as cooking and cleaning for the minshuku. Also, he really wants his nine-year-old daughter Yuzuki to learn English.

Yuzuki-chan plays the piano, and every day I would hear her plunking the same tunes, including the “Mickey Mouse Club March.” At first, the girl was a little shy, but soon my ukulele, magical singing Santa hat, and frisbee won her over. (I find that frisbees, games, and musical instruments help break the ice with non-English speakers. That worked in other countries like Indonesia and Vietnam, too.) By the end of the week, we were playing together every day. She would relax with me and Gosia at the kotatsu (heated table) at the end of the day, drawing pictures or teaching me Japanese.

Just like how his daughter has an atypical childhood, with a never-ending parade of foreigners coming and going, Atsushi is not your typical oyster farmer. He wants to change the way oysters are grown in Kumihama Bay, borrowing ideas from French, American, Australian, and Canadian farmers to make the process more productive and efficient.

When he took us out on the boat to see his platforms, he asked us to lift a cockle box and feel for ourselves how heavy it is. Both Gosia and I were able to lift it, but just barely! There is a lot of manual labor involved in oyster farming, and the process can be sped up with the help of simple tools like a metal hook to grab multiple boxes at once. Machines, such as one that Atsushi uses to break up the clumps of oysters, can also replace tools like hammers and streamline the process.

One of Atsushi’s oyster platforms

One of Atsushi’s oyster platforms

Atsushi thinks that rural areas in Japan need innovation, because populations are decreasing and young people don’t want to continue the work their grandparents started. Other farmers are reluctant to try new techniques because of their traditional values, but one of Atsushi’s goals in hosting volunteers is to collect ideas.

One night, he sat down with Gosia and I and asked, “What ideas do you have for me? What can I do to make your experience better?” I was really impressed with his openness. I have volunteered on ten farms in New Zealand, Australia, and Indonesia with the Help Exchange program (I wrote this articleabout it a few years ago), and I have never met a host who asked volunteers for advice.

After experiencing volunteering as a means of travel, I realize that sightseeing is exhilarating but exhausting. I don’t have a strong desire to do it for more than a few weeks. However, if I try to integrate into the community, make some friends, and feel like I’m contributing to something larger than myself, I can stay in each place longer, learn more, and make deeper connections. As I’m observing and internalizing, I constantly ask myself: what do I want to adopt or exclude from my own life?

Mostly, volunteering makes me realize that there are hundreds of people with different lifestyles than mine, and that there is more than one way to live on this planet. Before I traveled, I only had a narrow vision for what was possible. Now I realize that it’s possible to start a cashew factory in Bali to help a needy community, or to have a zero-impact life on a self-sustaining farm in New Zealand. I lived with these people and was able to see the world through their eyes. I’ve picked up skills like milking a goat by hand, chopping firewood with an axe, cutting sashimi, and more. I’ve learned the process behind how foods from kiwis to milk to oysters are cultivated.

Atsushi told me that when he went to Canada, his perspective expanded more than 100-fold. Every time I travel, I feel the same way. Every time I volunteer, I can entrench myself in a community and force myself to be involved in a way that sightseeing does not allow.

I’m planning to use Help Exchange to volunteer again. There are more people to meet, more skills to learn, and more adventures to have. I’m young, and I have the energy to do it, so why not?