This article originally featured in the October 2020 issue of Connect.

by Nathan Post (Yamagata)

True Popularity of Japanese Music as Seen Through the Lens of the Used Vinyl Bin

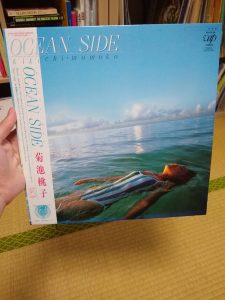

Walk into the vinyl section of any Japanese second-hand store, such as Hardoff, and you’ll be greeted by a selection of western classics, an even larger selection of jazz and fusion, and lastly, a plethora of Japanese music. Chances are, aside from one or two, most of the Japanese artists will be virtually unheard of by a western audience. The Japanese vinyl on offer usually spans the 70s to 80s, including a range of sonic styles that ebb and flow with influences from both the West and Japan.

Genre boundaries are always a bit nebulous, but traditional Japanese standard pop of the 70s and 80s is called kayoukyoku (Showa-era pop), and more western-leaning pop is referred to as J-pop or “pops.” “City pop” is another loose subgenre that is defined more by its vibe than any specific sound. It echoed the extravagance of life in the city and the maturity of a country that was rapidly becoming a tech and finance powerhouse. The term was originally used in the 70s and 80s but isn’t commonly known among Japanese people now. In the past few years, the genre has been experiencing a huge increase in popularity in the West. City pop was heavily influenced by soft rock, disco, boogie, and soul, and it was frequently packaged with tropical designs and summery imagery. The Doobie Brothers, Earth, Wind & Fire, early Sade and Janet Jackson have all made songs that neared the city pop sound and feeling.

While city pop names like Mariya Takeuchi, Tatsuro Yamashita, or Anri, (darlings of the YouTube “Up next” algorithm) are just beginning to poke into the consciousness of casual music listeners located in the West, they had already captured the attention of record collectors long ago. Mariya Takeuchi’s most famous song (at least according to plays on YouTube) is “Plastic Love,” with a view count of over 75 million spread over a handful of videos. Since “Plastic Love” has blown up online, the price of its physical media has also skyrocketed. Complete copies of the “Variety,” the album that it’s on, in decent condition sell for around 10,000 yen. This price doesn’t reflect the scarcity of the record (popular vinyl marketplace Discogs lists over 10 copies for sale) but rather the high levels of demand. This price trend is seen across the board for singles and albums that have recently become popular on YouTube.

While city pop names like Mariya Takeuchi, Tatsuro Yamashita, or Anri, (darlings of the YouTube “Up next” algorithm) are just beginning to poke into the consciousness of casual music listeners located in the West, they had already captured the attention of record collectors long ago. Mariya Takeuchi’s most famous song (at least according to plays on YouTube) is “Plastic Love,” with a view count of over 75 million spread over a handful of videos. Since “Plastic Love” has blown up online, the price of its physical media has also skyrocketed. Complete copies of the “Variety,” the album that it’s on, in decent condition sell for around 10,000 yen. This price doesn’t reflect the scarcity of the record (popular vinyl marketplace Discogs lists over 10 copies for sale) but rather the high levels of demand. This price trend is seen across the board for singles and albums that have recently become popular on YouTube.

Shifting to more obscure and less highly sought-after titles, you’ll find city pop albums that have sold for even more, such as Tohoku Shinkansen’s “Thru Traffic” or Piper’s “Summer Breeze,” two summery treats that easily command northwards of 20,000 yen. That said, the cult collector’s status attained by Japanese artists in the past few years doesn’t mean the majority of canonical, important, or otherwise high quality releases are out of reach for the typical listener or collector. Many of the most influential releases of the 70s and 80s were in high demand, and the surge in prices for a select few records doesn’t necessarily reflect what was popular at that time.

Thumbing through records in the Japanese vinyl section is often a better indicator of what is truly popular than relying on YouTube or online record sale prices. Stores like Hardoff often receive their used inventory from individuals who are moving or clearing out their houses. The selections usually represent portions of collections from average listeners. While there may only be the stray copy of albums with recently discovered city pop hits (even those that don’t sell for astronomical prices), one can often find an excess of Japanese “pops” and kayoukyoku superstars like Yumi Matsutoya and Momoe Yamaguchi, who are still relatively unknown outside of Japan. It’s easy to find good condition records by these artists for less than 2000 yen.

A quick check on most influential lists of Japanese artists confirms what the used vinyl bin inventory shows. HMV’s 2003 “Top 100 Japanese Pops Artists” places Yumi at #3 and Momoe at #7. A few city pop stars make the cut (Tatsuro Yamashita is at #6 and Mariya Takeuchi at #26) but others, including Anri, are excluded entirely. Yumi’s relative obscurity in the West is made even more surprising by the fact that a number of her songs were later used in the Ghibli movies Kiki’s Delivery Service and The Wind Rises. When I moved to Japan, I asked my coworkers for music recommendations. Time and time again, Yumi and Momoe were mentioned, and my teachers seemed honestly surprised that I wasn’t familiar with them considering I knew artists like Mariya Takeuchi.

A quick check on most influential lists of Japanese artists confirms what the used vinyl bin inventory shows. HMV’s 2003 “Top 100 Japanese Pops Artists” places Yumi at #3 and Momoe at #7. A few city pop stars make the cut (Tatsuro Yamashita is at #6 and Mariya Takeuchi at #26) but others, including Anri, are excluded entirely. Yumi’s relative obscurity in the West is made even more surprising by the fact that a number of her songs were later used in the Ghibli movies Kiki’s Delivery Service and The Wind Rises. When I moved to Japan, I asked my coworkers for music recommendations. Time and time again, Yumi and Momoe were mentioned, and my teachers seemed honestly surprised that I wasn’t familiar with them considering I knew artists like Mariya Takeuchi.

The delineation between city pop artists and those making other forms of Japanese pop isn’t as rigid as it may seem from the current emphasis and resurgence of the “city pop” genre in the West. Many Japanese people may be familiar with some of the artists involved but probably associate them with the big city sound of the 80s as opposed to the genre of city pop specifically. Artists blurred the lines themselves: Yumi and Momoe made a few albums that heavily featured city pop sounds, and Mariya and Anri made a number of albums in a more standard kayoukyoku style.

It’s easy to understand the current appeal of city pop; the mix of western styles and tropical aesthetic is approachable and groovy, but its current appeal suggests a level of popularity which it did not rise to when it was first released. Filtering and listening to music from eras gone by has certainly exposed some gems to a new audience, but it has also reinterpreted and crafted perceptions of a genre that aren’t historically accurate. If you want to connect with the mainstream sounds of the time, avoid the digital trappings of contextless singles, and check the physical releases near you.

Nathan is a second-year ALT from the USA living in Sagae City, Yamagata Prefecture. When he is not scouring the far corners of Japan for vinyl goodies, he enjoys hiking and also dabbles in DJing and hosting events.